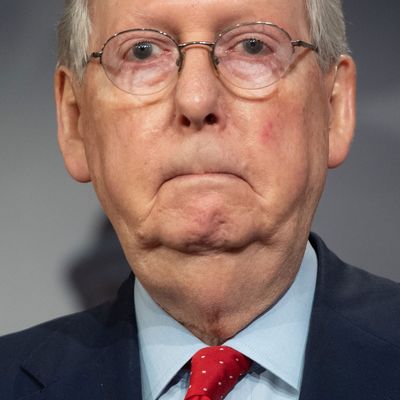

On June 15, 2012, the American Enterprise Institute hosted a speech portentously titled “Growing Threats to Our First Amendment Rights: An Address by Mitch McConnell.” (“Address” is the term politicians use for speeches they wish to be taken seriously.) The Senate Minority Leader used the hourlong remarks to warn that restrictions on political donations by corporations and wealthy people, or even mere disclosure requirements, were “an alarming willingness itself to use the powers of government to silence” dissent. Since “the form of speech most needful of absolute protection is political speech,” McConnell argued that President Obama’s efforts to require public disclosure of donations by figures like the Koch brothers amounted to the government “using its own powers to harass or intimidate those who participate in the political process.”

Whatever might be said about McConnell, here was an issue where not even his bitterest critics doubted his sincerity. Opposing campaign-finance reform as a dangerous restriction on political speech by businesses was the cause of his life. Obama’s memoir casually describes McConnell as lacking “any strong convictions beyond an almost religious opposition to any version of campaign-finance reform.”

And yet, last Monday, here was McConnell treating the spectacle of business leaders engaging in political debate as a stark threat to be extinguished. The provocation was a series of corporate statements denouncing Republican-sponsored voting restrictions, which McConnell described as “a coordinated campaign by powerful and wealthy people to mislead and bully the American people.” McConnell, invoking a spate of Republican proposals to punish firms that speak out against their vote-suppression laws, warned, “Corporations will invite serious consequences if they become a vehicle for far-left mobs to hijack our country.”

The next day, after reiterating his warning to corporations to “stay out of politics,” McConnell clarified that he did not mean to discourage their continued donations. Corporate money is speech, but speech isn’t speech.

The phantasmal threat of government intimidating business leaders for exercising their First Amendment rights, which McConnell had once invoked to ward off any limits on their ability to use financial leverage over elections, had suddenly become real. And the source of the threat is McConnell himself. A few days’ worth of large corporations condemning voter suppression has left the Republican leader so thoroughly rattled that he’s thrown away decades of laborious work reputation-building on the single issue that is the foundation of his worldview.

There is more at work here than the latest cynical turn of the wheel. McConnell is acting not only out of calculation but a mix of fear and rage that is enveloping segments of the right that believed they had come through the Trump era unscathed. For a certain class of Establishment Republican, the events surrounding Georgia’s voting restrictions have set off a mental crisis more severe than anything they experienced during the previous four years.

From the standpoint of the Republican elite — in particular, the conservative Republicans like McConnell who went along with Trump while cringing at his incompetence — the Trump presidency was an unpleasant period during which they were beset on all sides by impossible demands. To their right, Trump’s most ardent cultists disdained them as country-club insiders who resented Trump for inspiring a populist uprising that shook loose their control of their party. To their left, the media, liberals, Never Trumpers, and perhaps their neighbors and younger family members dismissed them as little Eichmanns working alongside a monster.

But what were they supposed to do? Impeach the man? Vote against tax cuts they believed would help the economy? It was all so unreasonable.

The nadir came on two consecutive days in January. On Tuesday, January 5, a surprising special election deposed the Republican Senate majority and gave Democrats a working government. The next day, a Trumpist mob ransacked the Capitol. In that moment, they finally snapped. McConnell delivered a searing speech blaming Trump. Even Lindsey Graham said he was done with Trump.

But the party faithful weren’t done. Trump’s lie that his sacred landslide election was stolen by fraud took hold among the party’s base. And so they responded by instituting a national wave of restrictive voting bills, beginning in Georgia, the epicenter of Trump’s grievance. It did not strike them as especially significant that the state is a literal crime scene (Trump is the subject of two ongoing investigations stemming from his efforts to pressure state officials to overturn the election results.) Nor did the symbolism of launching their vote-suppression program in a blue-trending former Jim Crow state strike them as especially provocative. Voter-suppression laws would, they hoped, advance the party’s electoral prospects by discouraging young people and racial minorities from navigating the bureaucratic requirements of voting.

More importantly, it healed the post-insurrection intra-Republican breach. While it looked to the outside world that they were flattering Trump’s lie, voter suppression was good old-fashioned mainstream Republican policy even before Trump came along. The conservative movement has argued for decades that the problem with voting is that too many people do it because it’s too convenient. “Voting is a privilege,” National Review’s Andrew McCarthy argues. (A privilege, not a right.) “It would be far better if the franchise were not exercised by ignorant, civics-illiterate people, hypnotized by the flimflam that a great nation needs to be fundamentally transformed rather than competently governed.”

McCarthy, importantly, criticized the insurrection and many of Trump’s lies about election fraud. His beliefs are not especially controversial on the right. Vote suppression sits at the intersection of Trump’s unique derangement and standard-issue conservatism. It is the sort of policy Republicans used to enact quietly, with little protest, back before everybody detested them.

To see dozens of corporations denounce voter-suppression laws has therefore come as a shock to the party’s elite. Nobody — nobody they cared about, anyway — was denouncing them for passing vote-suppression laws in 2010. They had begrudgingly accepted some level of backlash against Trump. But now Trump was gone, many of them had openly denounced him on his way out, and here they find themselves still on moral probation.

A sickening realization has settled upon them that many of the uncomfortable changes to the political atmosphere over the last four years may be permanent. The cultural change that alienated the GOP from academia and Hollywood years ago are creeping into corporate America.

A major reason for this is that the country’s economy has a leftward skew that is even more pronounced than the rightward skew of its political institutions. Counties that voted for Biden account for 70 percent of GDP. The young educated people that big companies disproportionately covet as customers and as employees are far more liberal than the median voter.

Whether this is “fair” is a matter of perspective. In theory, the people who accept the legitimacy of an outcome driven by capitalistic dynamics ought to be the party that talks about free markets like they’re the hand of God. And yet their capitalist principles have offered Republicans little comfort. Instead, Republicans have lashed out at the market that has forsaken them, angrily threatening policy retribution against any companies that oppose their vote-suppression agenda. A Wall Street Journal editorial denounces “woke and weak CEOs” leading a wide array of companies. Why, that sounds like the kind of systemic market failure the Journal is always insisting can’t happen.

One of the practical outcomes of the new right-wing alienation from corporate America is that it has demanded of its devoted followers an almost monklike commitment to asceticism. The sort of person who rejects mainstream culture and expresses values through alternative homegrown consumer channels used to be associated mainly with the left. Think of the neo-hippie in a hemp tunic shopping at the local organic-food collective. Suddenly, this consumer alienation is emerging on the right.

The Journal also recently published a column by a Republican lamenting all the brands that have politically alienated him. The list only begins with known villains like Delta, Major League Baseball, and Coke. “Moving to the bathroom, I encounter my progressive razors,” he laments, recounting how a Gillette ad attacked toxic masculinity and Harry’s pulled its advertising from Ben Shapiro’s website.

Between his blustery threats of retribution against his erstwhile corporate allies, McConnell sounds almost plaintive. “Republicans drink Coca-Cola, too,” he pleaded, “And we fly. And we like baseball.” If you prick us, do we not bleed? Perhaps he should try a little more introspection as to just how it came to pass that formerly anodyne corporate value statements, like “Voting is good” and “Racism is bad,” turned into divisive markers of partisanship.