When it comes to sports fans, there’s always someone willing to defend the indefensible. There are people out there who claim to enjoy Alex Rodriguez’s ramblings on ESPN’s Sunday Night Baseball, or who cheer for Boston-area sports teams, or who think golf is interesting. I wouldn’t want to get stuck with them on an elevator, but they exist.

Over the weekend came the first sports phenomenon I can remember that absolutely no one likes. On Sunday evening, 12 top European soccer clubs, including legendary franchises like Manchester United, Real Madrid, and AC Milan, announced that they were launching a new competition, constructed after months of secret negotiations, called “Super League,” which exists exclusively for the richest, most powerful clubs. The new league claimed in a release that it would split $4.2 billion in estimated revenues by essentially walling itself off from the other European leagues. This would completely upend — destroy, essentially — the entire structure of European soccer, much of which is buffeted by those top teams mingling with smaller, less wealthy teams.

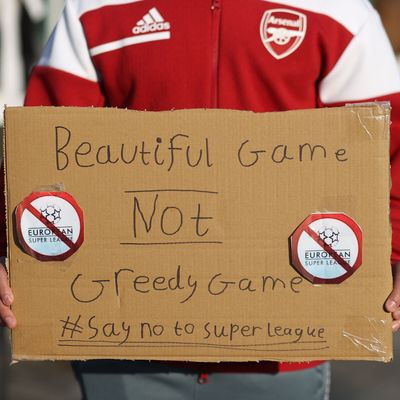

And people are furious. Furious! Everyone hates this thing. UEFA, the group in charge of European soccer, not only blasted the new league but claimed that any player on any of the teams involved in the Super League would be banned from international competition. (Which is a legally dubious threat but one all those players and their agents surely heard.) Prime Minister Boris Johnson of the U.K. has promised his government will do whatever is possible to block the new league, and the Spanish and Italian governments condemned it too. (There have even been calls for the European Commission to step in.) The top fan group for Liverpool, the club famous for its “You’ll Never Walk Alone” song/cheer, is removing all banners and flags from the team’s stadium in protest. Even Prince William was mad! I spent an embarrassingly large amount of time on Monday reading every British tabloid story about this I could find, and I must tell you, this American Midwesterner has now learned all sorts of new British vulgarities.

But what does all this mean? Here’s a handy FAQ on what’s happening:

Why are these teams doing this?

Money, obviously. That $4.2 billion split is theoretical, but JPMorgan has put up financial backing for the new enterprise, which means there’s definitely reason to think it could be a huge moneymaker. These are, after all, some of the best-known brands on the planet. Six of the top seven most valuable soccer teams in the world, according to Forbes, would be a part of the Super League. One should be careful about making American sports analogies to European soccer, but surely it would be a much bigger threat to Major League Baseball if the Yankees and Dodgers left to start their own league than it would be if the Marlins and Pirates did. When these teams make a move like this, it’s a seismic event.

The context of this move is important too. The UEFA Champions League, which brings the best Euro teams together in order to crown an annual champion, had been redesigning its title format and was involved with negotiations with some of those top teams on how to structure it. Specifically, those top clubs — some of which have American owners, like Arsenal’s Stan Kroenke (who owns the Rams, Nuggets, and Avalanche) and Liverpool’s John Henry (who owns the Red Sox) — wanted a greater say over how teams were chosen and the broadcast rights to the Champions League telecasts. UEFA had been scheduled to meet on Monday to finalize the league’s new structure. But the Super League announcement dropped an atomic bomb on that and on everything else.

Why is everyone so very mad?

European football is universal in a way that American sports are not. The wealthy clubs are inherently connected to the smaller clubs and are, in many ways, their subsidizers. The relegation structure of European soccer allows smaller clubs like Burnley and Watford to be a part of the same solar system as the monsters like Manchester City. There was always an unsteady balance between all these teams, but as long as they were in the same universe, they could coexist and potentially all thrive.

But one of the many ways COVID-19 changed sports was that it revealed that huge teams with television-rights deals could make money even if no paying customers were allowed in the stands, while smaller teams could not. It is much like the American financial system: Many smaller teams have just barely been holding on through the pandemic while richer teams got wealthier and wealthier. Now that fans are returning to the stands, those massive teams are trying to create an ecosystem exclusive to themselves. As Mark Ogden smartly put it at ESPN FC:

It is a ruthless, and maybe even cynical, approach, but those in charge know how it works. And if it becomes a closed shop without fear of relegation, the NFL and NBA are hugely successful business models to follow. United, Arsenal and Liverpool — three founding members of the ESL — are all owned by Americans involved in US sport, so they are already well-versed in how to capitalise on owning a franchise in such an environment. It is also clear that, with a future secure from relegation, all member clubs of the ESL would become even more valuable to their owners But once again, what about the fans? What about the families who have supported their club through generations, seen them succeed and fail, bought the tickets and the shirts, turned up in the cold and rain? The owners have bought their clubs, often without previous attachment or association. In the case of the Glazers at United, their takeover in 2005 was funded by using the club’s own money. And the same owners are now using historic clubs, rooted in their local communities, as bargaining chips to create a ring-fenced money-making machine that only they want.

It must be noted that the announcement throws all the women’s teams of these clubs under the bus: Lyon is essentially the Yankees of women’s European soccer, but no one even thought to ask them.

Is this really going to happen?

The backlash to the Super League has been truly overwhelming. It is as if someone shot Paddington. But the announcement was clearly well thought out: The Super League put in specific legal protections meant to offset UEFA’s punitive measures, which means this will end in court. There is still some thought that this is all just posturing by the Super League teams — a way to get themselves better terms involving the Champions League. But if that’s the case, they appear to have severely overplayed their hand. They’ve made UEFA, which is a truly terrible organization, somehow appear sympathetic. Any leverage the new league had is gone. They almost have to follow through with the Super League now, unless they’re willing to immediately drop the whole idea. (And it sure doesn’t look that way.)

This is already a historic moment: Either it’s a detonation of the whole sport or it’s an immortal embarrassment that none of these teams is ever going to live down. Whatever happens, European soccer will never be the same.

Why should Americans care?

This is actually an Americanization. U.S. sports leagues are essentially closed-off loops in which only a select number of teams get to share the profits among themselves and themselves only. No teams can be relegated out of American sports if they’re not successful, which, in many cases, disincentivizes teams and owners from spending to make their teams better. (This is a common complaint about some Major League Baseball teams, particularly during the pandemic.) It also disconnects the teams from their supporters, which is why so many fan groups have risen up in protest. You can try to make yourself forget a jerk like Stan Kroenke owns your team when you’re carrying the same Arsenal Premier League scarf you’ve had your entire life. It’s a lot harder when he destroys all that tradition just to maximize his stake in a corporation that also happens to be your favorite team. (A team the American billionaire doesn’t seem to understand in the first place.)

It is thus no wonder this is so hated in Europe: It reminds them of us.