The Democratic Party’s policies have delivered large wage increases to blue-collar workers, and at only a negligible cost to middle-class consumers.

This is, apparently, the GOP’s new message about the Biden economy.

Last week, the National Republican Congressional Committee (NRCC) — the body tasked with electing a GOP House majority — released an official statement spotlighting the fact that Chipotle workers had just secured a significant raise, a development that it attributed to Joe Biden’s “socialist stimulus bill.” But if you’re worried that the conservative movement is about to endorse collective control of the means of production, fear not: The NRCC’s “press update” was not a celebration of a wage increase, but rather a lamentation of a price hike:

As you can see, the GOP did not bother to conceal the Times’s reference to “increased employee wages.” Which gives the NRCC’s statement a remarkable subtext: The Republican Party believes that raising the pay of Chipotle workers is less important than suppressing inflation in the all-important, customizable burrito-bowl sector.

A columnist for the GOP-aligned publication The Federalist made this case explicitly, fuming, “Life is breezier on unemployment than behind the Chipotle counter, so the franchise is trying to lure workers back — but it’s making my lunch more spendy.”

This is an odd argument for a self-described “working-class party” to make. Republicans could have couched their opposition to federal unemployment benefits in (speciously) pro-worker terms, by, for example, casting themselves as champions of the humble waitress whose hard labor leaves her with less spending money than her unemployed, layabout neighbor. Instead, the party is openly proclaiming its indifference to blue-collar wage gains.

And its position is even stranger upon close examination. Chipotle is raising wages by $2 an hour per employee. A typical wage for a server at the company was $11 an hour last year. So we are talking about a roughly 18 percent increase in wages, at the cost of a 4 percent increase in prices — or a roughly 30-cent uptick in the cost of a burrito bowl. To cast this tradeoff as self-evidently undesirable is to advertise one’s contempt for service workers.

For these reasons, the GOP’s “the burrito prices are too damn high” argument became a subject of mockery on the broad left-of-center. Yet, if liberals found the GOP’s priorities risible, some accepted one of the NRCC statement’s core premises: If employers raise wages for working-class laborers, middle-class consumers will inevitably pay the price.

Ezra Klein made a progressive version of this argument in a piece titled “What the Rich Don’t Want to Admit About the Poor.” The bulk of Klein’s column is factually sound and morally righteous. He writes that the “American economy runs on poverty, or at least the constant threat of it” due to its structural dependence on cheap labor; that a significant number of Americans benefit from that fact; and that those Americans should nevertheless support better pay and social benefits for the working class. All of which seems hard to dispute.

A large segment of the U.S. working-class has negligible savings, no access to collective bargaining, and meager welfare benefits, thanks to the exceptional stinginess of America’s welfare state. These realities leave millions of U.S. workers desperate for income — and thus willing to accept employment on any terms, even if those include poverty wages, irregular schedules, hazardous work conditions, or being routinely robbed by one’s employer. Last year, one-quarter of American workers earned less than two-thirds of their nation’s median wage; in no other developed country was the share of “low wage” laborers so high.

The abnormal exploitability of U.S. workers has become a normal operating condition of the U.S. economy. It’s been half a century since full employment was a routine feature of American life. For most of the past two decades, mass underemployment has been the norm. As a result, the presumption of cheap labor’s perpetual availability now undergirds the business models of multibillionaire-dollar companies like Uber, and countless small firms with low profit margins. Meanwhile, many upper middle-class consumers have developed lifestyles contingent on labor’s weakness; if jobs were more abundant, or life “breezier” on unemployment, urban professionals’ taxi rides and grocery deliveries might become a bit more “spendy.” As Klein puts the point, “those in the economy with the power to do the dictating profit from the desperation of low-wage workers. One man’s misery is another man’s quick and affordable at-home lunch delivery.”

But one can take this argument too far. And I think Klein ultimately does.

His column argues, through a quote from U.C. Berkeley economist Hillary Hoynes, that “it is a fact that when we pay workers less and don’t have social insurance programs … we are able to consume goods and services at lower prices.” And in its closing paragraphs, Klein suggests that America, as a society, must choose between the “luxuries and comforts” enjoyed by the middle class and the abolition of poverty, through full-employment macroeconomic policies and generous welfare programs.

But I think we can have both.

In a high-wage economy, with a plush safety net, some goods and services beloved by urban professionals today might become less affordable, at least for a time. And there is no question that the top 10 percent of earners would see their overall share of income and wealth shrink in such an economic order, if only due to the taxes and transfers inherent to a comprehensive welfare state.

But the notion that middle-class Americans can’t enjoy rising living standards unless working-class Americans live on the edge of poverty is not only wrong. It’s quite plausibly the opposite of the truth. Firms can make goods and services cheaper by driving down wages. But they can also do so by increasing productivity. And there’s substantial evidence that loose labor markets — and hyper-exploitable workers — are actually impediments to productivity growth.

There is an intuitive way in which high wages can lead to higher productivity: When a firm’s workers feel appreciated and economically secure, they may perform better at their jobs, and stay with their employers for longer. For this reason, a firm might find it more profitable to raise wages than to keep them low, since the former yields higher output and lower turnover. In recent years, a variety of studies have suggested that, in several U.S. sectors, wages are lower than consumers or bosses should want them to be.

But there is another way that a low-wage economy can undermine productivity: So long as there’s a deep reservoir of humans who will perform simple tasks for subsistence wages, employers have little incentive to invest in labor-saving technology, or to innovate more efficient production techniques. By the same token, when the cost of labor rises, firms are often forced to increase productivity in order to survive.

Ironically, Klein offhandedly references this relationship between high wages and productivity growth when cataloging the potential costs of eliminating poverty, writing, “There are services many of us enjoy now that would become rarer or costlier if workers had more bargaining power. We’d see more investments in automation[.]”

The two concerns Klein cites here — higher prices and more automation — routinely appear in conservative polemics against proposals for aiding the working poor. Yet there is an obvious tension between the claims. When you automate a service or production process, you eliminate labor costs and (generally speaking) lower consumer prices.

It’s easy to make a logical argument for why higher wages would lead to more automation. Making an empirical case for the connection is a bit tricker. But in 2018, the economists Grace Lordan and David Neumark found a way. Reviewing 35 years of government census data, they identified jobs that were readily automatable given existing technology, and found that after minimum wage increases were enacted, “the share of automatable employment held by low-skilled workers” went down. Put differently, minimum wage hikes encouraged capital investment, and increased productivity by automating tasks that did not require uniquely human skills. (Curiously, conservatives cast this as an argument against raising the minimum wage, even as they justify cutting taxes on the wealthy on the grounds that doing so will encourage capital investment and increase productivity.)

By dramatically increasing worker pay across an economy, at a single point in time, minimum wage hikes offer a (relatively) easy way to isolate the impact of higher labor compensation on automation. But there’s no reason to think this effect is peculiar to minimum wage increases. Any force that renders labor more expensive presents employers with the same imperative to do more with less. And if that force is a full-employment economy — and/or a welfare state that enables workers to enjoy a modicum of economic security while job hunting — then automation will have a relatively low cost for displaced workers.

To be sure, real harm would remain; losing a job tends to be painful, even in the best of circumstances. But if our economic system has any noble purpose, it is the liberation of human beings from needless drudgery. There is no reason why the automation of the supermarket checkout process must leave grocery clerks with less money rather than more time to exercise their uniquely human passions and abilities. Automation increases our collective wealth. And, at least as a technical matter, that wealth can be shared.

The historical record supports the notion that full employment spurs investment in labor-saving technology just as surely as minimum wage hikes do. As the New York Times’s Neil Irwin observed in 2017, over the past seven decades of U.S. history, labor-market booms tend to be followed by productivity booms, while deep recessions give way to productivity slumps.

Roosevelt Institute economist J.W. Mason contends that this correlation explains one of the great mysteries of contemporary economics: why productivity grew so much faster during the postwar period than it has over the past five decades. Conventional wisdom holds that weak productivity gains caused the tepid wage growth of the past half-century. But Mason’s theory inverts this story. After the stagflation crisis of the 1970s, policymakers in the U.S. and elsewhere began prioritizing inflation prevention over full employment; whenever labor markets grew tight, and wages started to accelerate, central banks raised interest rates to “cool off” the economy. In so doing, they didn’t just preempt strong wage growth for the bottom half of their domestic labor forces, in Mason’s telling, but also preempted the mass deployment of labor-saving technologies.

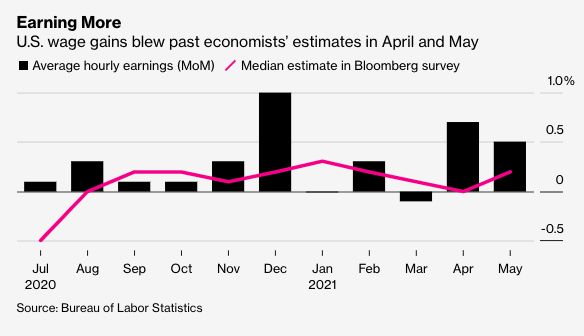

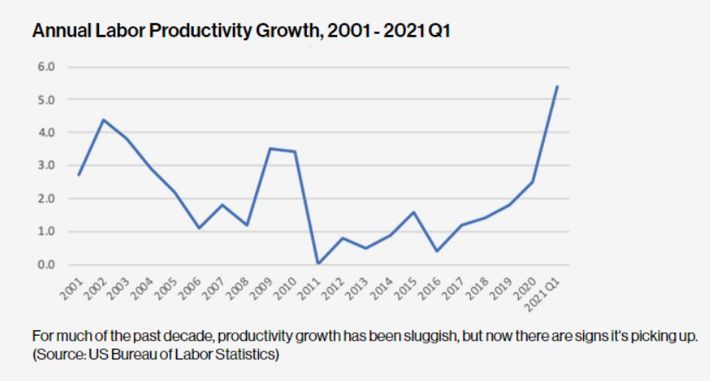

In the last few years, policy has changed. Today, the Federal Reserve is keeping interest rates low despite signs of inflation in some sectors, while generous federal unemployment benefits have tightened labor markets. And there is some evidence that this prioritization of jobs and wages is working as Mason’s theory would predict. In April and May, wage growth far exceeded economists expectations, as a wide array of large employers lifted their base pay rates to lure more workers off the labor market’s sidelines. As Noah Smith notes, over roughly the same period, productivity growth rapidly accelerated:

It is possible that these gains merely reflect firms capitalizing on efficiencies that the pandemic forced them to discover (such as the optimal utilization of remote work). But the trend is nevertheless consistent with the “high wages drive high-productivity” theory.

Notably, according to one of that theory’s most prominent adherents, high labor costs actually spurred the Industrial Revolution itself. The great economic historian Robert Allen has observed that, in the late 17th century, China was every bit as formidable a civilization as Britain, and had comparably advanced machinery. The tools of industrialization were right there at its disposal. And yet, it was the far smaller island empire to China’s west that crossed the rubicon into economic modernity. Allen insists that Britain’s divergent path was a product of its relatively high wages, in combination with its abundant coal supplies. In China, businesses’ access to cheap labor dulled their interest in investing in machinery. In Britain, by contrast, the relatively high cost of a workman’s hour — and relatively low cost of carbon energy — motivated the advent of the steam engine, and myriad technologies that harnessed its power.

Allen’s theory has some critics. What is inarguable, though, is that (1) wages rose much faster in Britain than in China over the course of the Industrial Revolution, and (2) that relatively high wage growth did not come at the expense of the British bourgeoisie’s “luxuries and comforts.” The median 21st-century British worker is harder to coerce into labor than the median 17th-century British peasant. But that does not mean that the living standard of a minor feudal lord was higher than that of today’s typical junior executive. There is no inexorable tradeoff between rising wages for workers and rising living standards for elites.

Granted, productivity gains have historically been much stronger in manufacturing than in services. And the U.S. is today a service-driven economy. But advances in AI are already facilitating the mechanization of even “high-skill” service jobs. And according to an estimate from McKinsey, one-third of existing U.S. jobs could be performed by technologies already in existence, or else, likely to reach maturity by 2030. Which is to say: If generous welfare programs and full employment forced firms to compete less over how little they can pay workers — and more over how much labor they can save — then goods and services in the U.S. would likely become much cheaper than they are today. (Mechanizing production of the made-to-order burrito bowl will be difficult, no question. But a country that split the atom and flew to the moon should be up to the challenge.)

The highest-earning 10 percent of Americans might fare better under our status-quo political economy than they would in a low-poverty, high-wage one. But given the link between high wages and technological advance, even this is far from certain. The vast majority of middle-class Americans, meanwhile, would enjoy higher living standards in a low-exploitation economic system.

That’s a point worth emphasizing. Appealing to the better angels of people’s nature is nice. But in American politics, appealing to the low-key sociopathy of the affluent rarely hurts.