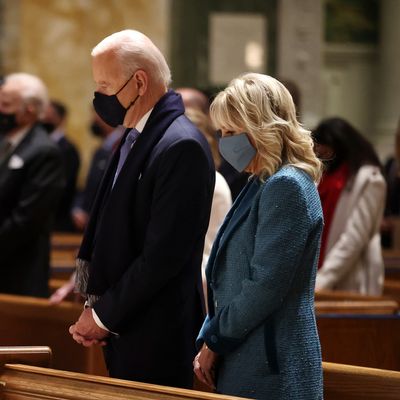

Joe Biden is the second Roman Catholic to become president, winning the White House 60 years after John F. Kennedy. He is also arguably the most religiously observant president (as measured by regular worship-service attendance) since Jimmy Carter.

So it’s somewhat shocking that the U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops, acting against the public and private advice of the Vatican, took a deliberate step during its spring meeting to draft and promulgate a “document on the Eucharist” that some proponents said was intended to lead to the denial of communion to the president and other prominent pro-choice Catholic politicians. The vote, after a brief but intense debate, was 168-55, with six abstentions. The margin is significant because adoption of the statement the bishops are contemplating (possibly for release as early as November) would require a two-thirds vote. It would also require advance review by the Vatican, which could slow down or even halt the condemnatory action as well.

Barring something really unprecedented, however, the ultimate decision on allowing or denying communion to Biden and other politicians on the basis of their public policy positions on abortion (or other issues like same-sex marriage) would be up to individual bishops, and in some cases individual priests. The two most relevant bishops for the Biden family, in Washington, D.C., and Wilmington, Delaware, are not in the aggressively conservative camp of those pushing for a “statement” clarifying the obligation of communicants (particularly those in highly visible public offices) to support church teachings. But the president can’t be at home at the White House or in Delaware every Sunday, so a landscape of hostile bishops or priests (like the parish priest who denied Biden communion in South Carolina in 2019) would be embarrassing if not problematic.

The conservative episcopal move against Biden may have simply been designed to ramp up the stakes in a more general culture war against “liberals,” against Democrats, or even against Pope Francis, who is resolute in his views on abortion but is notably friendly toward Biden. Some of the same U.S. bishops who want to sanction or intimidate Biden have been part of a religiopolitical resistance to Francis’s decidedly untraditional views on climate change, poverty, and the relative significance of social and cultural issues. Indeed, the New York Times viewed the vote on a “statement” as a power move by a Catholic “conservative movement” that is in near-open revolt against the Vatican:

It was the most dramatic example of the conservative Catholic movement’s reach since Mr. Biden was elected. But the contingent had been gaining strength throughout the Trump era, clashing with the Vatican, wresting influence away from Pope Francis’ top representatives in the United States and further polarizing the Catholic faithful in the process …

Leading U.S. allies of Pope Francis, including Cardinal Blase Cupich of Chicago, Cardinal Joseph W. Tobin of Newark and Cardinal Wilton Gregory of Washington, sided with the Vatican’s warning against proceeding with the eucharistic document, but they were ultimately drowned out.

The decision to push ahead on the statement may also have reflected some of the excitement in the anti-abortion movement (in which conservative Catholics have closely cooperated with conservative Evangelicals) over the possibility that the U.S. Supreme Court will reverse Roe v. Wade in its next term and return abortion policy to legislative determinations (and thus to day-to-day partisan politicking).

Both sides in this dispute are careful to couch their views as consistent with traditional Catholic reverence for communion (or the Holy Eucharist as it is more formally known, a Church sacrament central to the Mass), with conservatives claiming that obedience to key Church teachings is part of “worthiness to receive communion,” while their opponents warn against “weaponization of the Eucharist” for political purposes. This argument may seem odd to Protestants, who by and large do not limit access to communion to members of their own denominations, and who typically have less fear of profaning the ceremony with unworthy communicants. But the intra-Catholic argument does reflect broader tensions over church-state relations and religious-secular cooperation, with one key difference: Thanks to the Catholic emphasis on regular mass attendance, it’s not easy for Biden to emulate predecessors like Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush in professing personal piety without often going to church.

So far neither Francis nor his friend in the White House has commented publicly on the bishops’ implicit threats. As Jason Horowitz noted, the pope’s silence may simply reflect differences with the U.S. hierarchy that are just part of the landscape: “The divergence of the conservative American church from Francis’ agenda is now so apparent as to become unremarkable, and Vatican officials and experts said Saturday that the pope’s silence also underlined just how unsurprising the American vote, made public on Friday, was to the Vatican.”

The most fundamental issue is how regular lay Catholics in the pews will react to this fight. American Catholics routinely disregard Church teachings on contraception, and, according to all available evidence, are as likely to favor legalized abortion and same-sex marriage (not to mention divorce-and-remarriage and full equality for women in the clergy) as are other Americans. The conservative bishops are picking a fight that they may not only lose in the context of world Catholicism, but in their own parishes.