This week, in a strongly worded bid to dispel fears that he has subordinated voting rights to the more tangible material benefits contained in his 2021 agenda, President Biden attacked the Republican voter-suppression laws being enacted in a growing number of states, and called on Congress to make June a “month of action” on this subject.

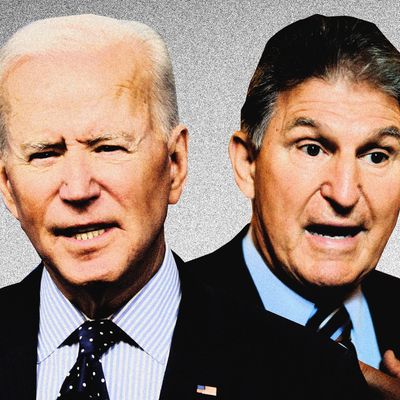

Biden’s most pointed remarks to date on voting rights came in the symbolically powerful spotlight of centennial commemorations of the Tulsa Massacre of 1921. He mentioned both the For the People Act (S.1), the comprehensive federal election law that has passed the House twice; and the John Lewis Voting Rights Act, which is under development in both congressional chambers. And he clearly implicated Democratic senators Joe Manchin and Kyrsten Sinema for vocally opposing the kind of filibuster reform that might make voting-rights legislation possible given near-unanimous Republican opposition:

I hear all the folks on TV saying, “Why doesn’t Biden get this done?” Well, because Biden only has a majority of effectively four votes in the House and a tie in the Senate. With two members of the Senate who vote more with my Republican friends, but we’re not giving up.

The two renegade centrists are not, to be clear, identical on voting rights. Sinema is a cosponsor of S.1, and cosponsored the John Lewis Voting Rights Act in the last Congress, while Manchin has expressed concerns about S. 1 and only supports the John Lewis bill if the crucial Justice Department pre-clearance requirement is expanded to all 50 states. But both senators have repeatedly opposed any sort of carve-out for voting rights legislation that would protect it from the filibuster, which in a 50-50 Senate is the crucial issue.

Clearly Biden’s “month of action” appeal was an allusion to Chuck Schumer’s announcement that S.1 would come to the Senate floor on the week of June 21. So the president is very publicly ratcheting up pressure on Manchin and Sinema to both support the legislation and to support whatever measures are necessary to enact it despite GOP opposition. Biden wants credit for making an effort on voting rights, and might even deserve it — particularly if he follows up, which he hinted he would do, with a more focused speech on the subject.

But the important thing to understand is that Manchin (who is up for reelection in 2022) and perhaps Sinema (whose current term ends in 2024) aren’t exactly shrinking in terror in the face of presidential pressure. Biden won 29.7 percent of the vote in Manchin’s state last year. The West Virginian would probably pay cash money to secure as much criticism from the White House as possible. And even Sinema, from the dead-even state of Arizona, seems committed to an extraordinary degree to a 1990s-style triangulation strategy based on visibly annoying progressives. Or at least you got that impression when she infuriated a lot of Democrats earlier this year with a highly demonstrative thumbs-down gesture on a $15 minimum-wage amendment to the COVID-19 relief and stimulus bill.

And if Biden is a paper tiger when it comes to forcing party discipline on the centrists, Vice-President Kamala Harris, named the administration’s point person on voting rights, likely won’t fare better.

If you want to be Machiavellian about it, you could almost suspect Manchin and Sinema might come to the aid of their party on the filibuster generally, or voting rights specifically, after sufficiently demonstrating their independence. But it’s hard to square that theory with the categorical language that Manchin in particular has deployed, as in this April Washington Post op-ed:

Designating each state with the same number of senators — regardless of the population — ensured that rural and small states and the Americans who live in them would always have a seat at the table.

The filibuster is a critical tool to protecting that input and our democratic form of government. That is why I have said it before and will say it again to remove any shred of doubt: There is no circumstance in which I will vote to eliminate or weaken the filibuster.

He didn’t say he had yet to become convinced Republicans would obstruct Joe Biden’s agenda; he said it didn’t matter, he favored the filibuster as a matter of principle, and as a vital protection for his state. The president has no choice but to pound away on this issue in order to vindicate the trust of the Black elected officials and voters who lifted him to the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination and then supported him strongly last November. But it’s more than likely any success he achieves will be via his Justice Department’s voting-rights litigation, and the slow but steady effect of judicial nominations.