A Democratic mayoral primary that mostly played out in the tiny confines of a square box on Zoom spun into full Technicolor berserk in the race’s final days.

Candidates flung accusations of racism, anti-Semitism, and sexism at one another with abandon, even calling into question the integrity of the ranked-choice system some are using to form strategic alliances. But the tumult made it clearer what kind of mayor each of the top-tier candidates would be.

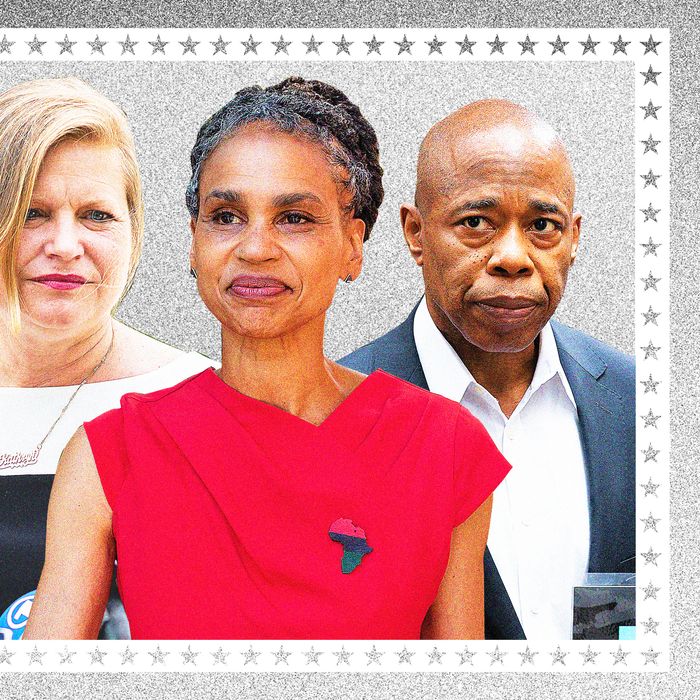

There was Eric Adams, who is running as such a law-and-order candidate that he received support over the weekend from both Rudy Giuliani and one of the few Republicans in the City Council, rushing to the scene of high-profile shootings and stabbings and accusing his opponents of conspiring to keep a “person of color” out of City Hall. There was Kathryn Garcia, ever the technocrat, trying to find efficiencies in the ranked-choice system to jack up her chances of winning. There was Andrew Yang, banking on pure exuberance and eliding the questions of whether or not he has the experience to govern. And there was Maya Wiley, continuing to stoke the passions of the left, which she has long hoped would carry her over the finish line.

The big story of the race’s final days was the alignment of Yang and Garcia, designed to keep the news on both of them but also to hurt Adams on at least two fronts.

First, they hoped to hold his numbers down in the initial round of balloting. An Ipsos poll from Monday had Adams at 28 percent, which is roughly in line with where other public and private polls put him. The key in a multi-candidate ranked-choice election is to keep the front-runner below 35 percent or so on the first count — anything higher than that, and he is likely to be ranked second or third on enough ballots to push him over the 50 percent threshold required to declare victory. The margin between Adams and whoever is second or third matters less than keeping the front-runner in the low 30s or less. And so while the bulk of the attention was focused on Yang enthusiastically endorsing Garcia for No. 2, keeping Adams lower-ranked on as many ballots as possible, or off of them altogether, gives Yang an advantage too.

Second, Adams’s rivals hoped that the alliance would bait Adams into calling the gambit a racist attack against him, potentially turning off some of the conservative white voters who, while supportive of Adams’s law-and-order platform, may be wary of someone willing to play up charges of racism.

After the announcement, Adams, who is running as the candidate of the city’s forgotten Black and brown neighborhoods, cried foul, accusing Yang and Garcia of trying to keep a Black candidate from City Hall — and on the first Juneteenth to be celebrated as a federal holiday. “Yang’s attitude was, We want to make sure we are keeping Adams and others out of the place of mayor,” he told CNN, likening the tactic to a “poll tax.” His campaign supporters went further. In an official release from Adams’s campaign, Ashley Sharpton, daughter of the Reverend Al, said it was an attempt “to steal the election from us.”

It is the kind of teaming up that is only possible under the ranked-choice system, which asks voters to not just select their preferred candidate for mayor, but to rank them in order of preference, No. 1 through No. 5. The alignment drew guffaws, appearing to be rather one-sided: Garcia refused to say that she supported Yang as her second choice, nor would she encourage her voters to do the same, while Yang led the voters of Flushing in a “GAR-SEE-AH! GAR-SEE-AH!” chant to rank her second.

According to sources within both campaigns, there was no deal for either side to say that the other was its No. 2 choice, but with Yang’s kid-in-a-candy-store excitement and Garcia’s mother-of-a-kid-in-a-candy-story reserve, few were surprised it went the way it did.

The campaigns had only begun talking a few days before the announcement about stumping together was made. As every candidate figured out how to work RCV, experts on the system said this was precisely the kind of move candidates ought to make to give themselves an advantage: Get an opponent with a fervent core of supporters to tell their voters to rank you second.

The appeal for Garcia was clear: No one has more fervent supporters than Yang, as anyone who has been swarmed by the Yang Gang on Twitter can attest. And for Yang, who had seen his prospects fade in recent days, the hope was that Garcia, who has based her campaign on her management ability, would be implicitly indicating to her supporters that she thought Yang was up to the job of mayor too.

When Yang wasn’t campaigning alongside her, he was in front of the Barclays Center for the Nets playoff game, leading an “Andrew Yang!” chant and bro-hop, or making an unannounced visit at 1 a.m. to Mission Nightclub in Koreatown, where he bathed in the adulation of the crowd. Candidate Yang has faced questions about his knowledge of and readiness to lead the city’s government and never attempted to address them much in the course of the campaign. It is easy to imagine that a Mayor Yang wouldn’t much address them either but instead continue to pop up wherever the party was.

As for Wiley, she was a bit out of the news cycle in the race’s final days, even as she kept up a relentless pace of campaigning. Wiley always had one of the widest paths available to any of the contenders. A candidate who can appeal to both white progressives and Black moderates, she divided her time between the two, attending a farmers’ market in Sunnyside, Queens, with former HUD secretary Julian Castro and State Senator Mike Gianaris, then a Juneteenth celebration in southeast Queens, then an event called Celebrating Black Trans & Queer Joy as Liberation in Harlem, before heading off to a Jews for Economic and Racial Justice event at Grand Army Plaza on Saturday night and a service at Brown Memorial Baptist Church on Sunday. Her campaign rested its hopes on the get-out-the-vote operation of her supporters, especially SEIU 1199 and left-wing activist groups. It is easy to see that, as mayor, Wiley would be stoking that same base of support, much as Bill de Blasio has.

As for the Yang-Garcia alliance, Wiley said both that she wouldn’t participate in any joint campaign efforts with Yang and that it was wrong of Adams to stoke fears of illegitimacy or of racism in the race’s final days. Her point was plain: With less than 36 hours to go, it was all against all.