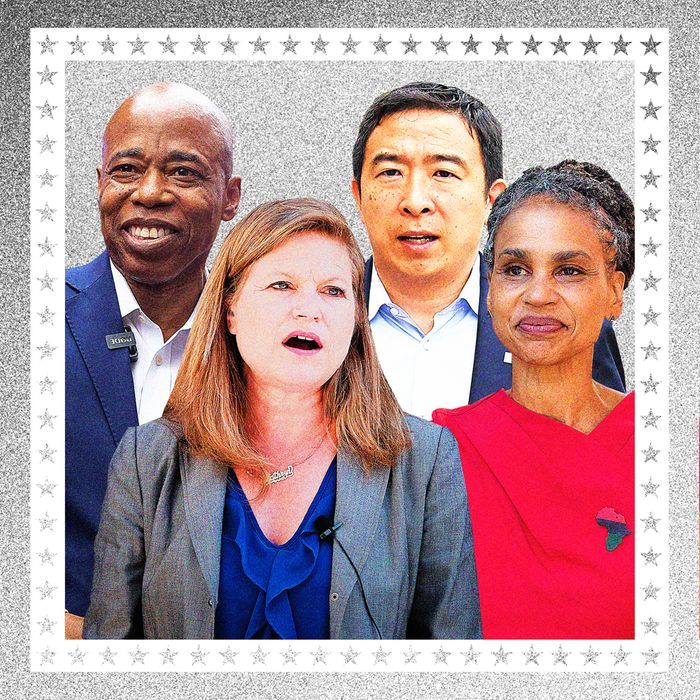

Can Eric Adams hold on to his lead?

That’s the question of the mayoral race after the polls closed on Tuesday, showing him as the first choice of about 30 percent of voters in ranked-choice voting. Battling for second place, and a shot at Adams, are Maya Wiley and Kathryn Garcia. The previous front-runner, Andrew Yang, fell to fourth place and has already conceded. Scott Stringer is a distant fifth.

Speaking at an election night party in a Williamsburg night club festooned with disco balls, Adams seemed overwhelmed with joy as he stopped just short of declaring victory, proclaiming “New York City said our first choice is Eric Adams.”

During a freewheeling, 40-minute speech he alternatively took shots at the media, celebrated an extended roll call of endorsers standing behind him, and offered an extended tribute to his late mother who passed away in March. Adams in particular spoke about the plight of Black New Yorkers, who are his base. “If Black lives really matter, it can’t only be against police abuse,” said the man who was beaten by cops as a teenager and then became an officer himself. “It has to be about the violence tearing apart our communities,” he continued, adding that the city needs to do more to secure affordable housing as well. It was a performance that captured all of the reasons why Adams won the most first choice votes of any candidate.

Adams’s wide lead over his closest opponent makes him the favorite to win, though he still needs to earn enough voter preferences under the ranked-choice system to reach 50 percent plus one. (The next round of voting calculations will begin on June 29.) That could be a challenge for a candidate who spent much of the final weeks of campaign courting controversy. In theory, his polarizing personality could hold him back in later rounds if voters decided not to rank him at all. This ranked-choice element was behind the alliance between Garcia and Yang, with Yang urging his supporters over the weekend to rank her second on their ballots. The result of Yang’s endorsement will be borne out in following rounds, potentially boosting Garcia into position to take on Adams.

Adams dominated the vote in the outer boroughs home to most Black and brown residents, running as a “blue-collar” candidate with appeal to middle- and working-class voters broadly. His message almost singularly emphasized fighting crime (the top issue among all Democratic voters) while also reforming the NYPD, given his past as a victim of police brutality as a teenager and outspoken critic of the department as a police captain. He campaigned on increasing the NYPD’s budget and presence on the streets after many candidates initially embraced “defund the police” rhetoric following citywide protests against the police last summer.

The front-runner hit an obstacle in the last two weeks of the campaign, after Politico reported it wasn’t at all clear where exactly Adams spends the night: in his Borough Hall office, in a Bed-Stuy brownstone he owns, or in a Fort Lee, New Jersey, condo. Rivals pounced on the possibility that he may have not been living in the city he wants to lead as mayor. Adams then gave the press a tour of the basement dwelling where he said he rests his head, including a look at the bathroom, bedroom, and inside the refrigerator.

Then Adams spent the final days of the race accusing Yang and Garcia of racism because they dared to team up at his expense — going so far as to compare their alliance in the ranked-choice voting system to a Jim Crow “poll tax” used to suppress Black voters. (His campaign says he was talking about how his own supporters felt.) Adams drew widespread condemnation for such a baseless claim.

Tuesday’s results represent the beginning of the final stage of an election that has been bizarre even for New York, taking place during a pandemic that made candidates spend more time in Zoom forums than politicking outside subway stations. Of the top-four Democratic finishers, three have never held elected office (Garcia, Wiley, Yang) and one is a former Republican (Adams). The city has never elected a female leader and has had only one Black mayor in four centuries.

When this year’s race began to take shape, one of the two candidates expected to be a front-runner didn’t make it to the starting line. City Council Speaker Corey Johnson dropped out of consideration, citing mental-health issues. (He later ran for city comptroller.) The other was Scott Stringer, the current comptroller and a veteran politician who forged a coalition between good-government liberals, like those in his Upper West Side home base, and young leftists, such as the insurgent candidates he endorsed before they went on to win a string of elections. They backed Stringer for mayor — until a past allegation of sexual misconduct led them to flee almost instantaneously, just as he hoped to gain on Yang and Adams in the final two months of the campaign.

Meanwhile, Yang had entered the race fresh off his gadfly presidential campaign, which saw him get more attention than actual votes. Armed with high name ID and a happy-go-lucky personality that netted him free media coverage, Yang shot to the top of polls. Yang resided in the center of the Democratic field, with a campaign led by a Michael Bloomberg veteran who once likened him an “empty vessel” and a message that included supporting law enforcement in the midst of a wave of violent crime and an unprecedented surge of attacks on Asian Americans, who comprise a large segment of his base. (The only areas Yang appeared to have won outright were Chinatown in Manhattan and Flushing, Queens.)

As any front-runner can testify, the position eventually leads to scrutiny by voters and attacks by rivals, who, in Yang’s case, resented the rise of the political neophyte who had never previously voted in a municipal election despite living in the city for 25 years. In the final month of the campaign, Yang’s lead gave away to Adams.

As Yang faded, Wiley became Adams’s new nemesis owing to her polar-opposite stance on policing. Among the final four candidates, she’s been the most vocally supportive of the defund-the-police movement and previously chaired the Civilian Complaint Review Board, which has some oversight of the NYPD. She attacked Adams in debates for his qualified embrace of the police use of stop and frisk and for saying he would carry a gun as mayor. She surged in the final days by consolidating the progressive vote — as seen in her strength in parts of Queens, northwest Brooklyn, and Park Slope — but struggled to find a clear path forward with Adams leading among Black voters and Garcia leading among good-government white liberals concentrated in Manhattan. The hope was that ranked choice would give Wiley a path forward as the second choice for Garcia’s voters.

Garcia was perhaps the most unexpected person to enter the top tier of candidates. A longtime bureaucrat who ran the New York City Housing Authority and the Sanitation Department under Mayor de Blasio, Garcia languished in the single digits in polls until she was endorsed by the New York Times editorial board. Around the same time, she made hay off repeated praise by then-front-runner Yang. “It’s totally sexist. Totally sexist,” she told The New Yorker. “Are you not strong enough to actually do this job, without me helping you? You should be strong enough.” However, Garcia mostly refrained from attacking rivals and focused on her message as the most competent candidate to run the nation’s largest city.