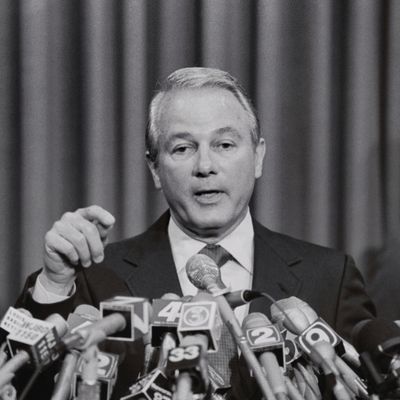

To call Edwin Edwards “colorful” is like saying Cajun cuisine is “spicy.” It’s true, but the word is hardly adequate in describing the reality. The former four-term governor of Louisiana has died at the age of 93 of natural causes, surrounded by family members, including his 41-year-old third wife, Trina, and his 7-year-old son, Eli.

At various points in his long life, in addition to his gubernatorial terms, Edwards was a Pentecostal preacher, a councilman in the small southwest Louisiana town of Crowley, a state legislator, a congressman, an associate justice of the Louisiana Supreme Court, chief librarian at the Oakdale Federal Correctional Institute (where he was inmate #03128-095), and even a reality-TV star. His accomplishments as governor included a key role in shaping the current Louisiana Constitution, a successful effort to tie oil and gas royalties to market prices, and the abolition of party primaries in favor of a nonpartisan “jungle primary” requiring a majority vote (then a general election “runoff” for election). But mostly he was legendary for personifying Louisiana’s taste for lovable populist rascals in the tradition of Huey and Earl Long even as the state drifted toward its current condition as a Republican-dominated bastion of economic and cultural conservatism.

Edwards grew up poor in Cajun country (his father was half creole and a Protestant; his mother, a Catholic, was actually descended from French settlers who bypassed Acadia) and never forgot it. His persona was that of a Robin Hood who fought for the dispossessed but was perpetually willing to cut himself and his friends and family in on every deal. In the Louisiana style, he often courted the appearance of impropriety (his reputation as a womanizer and his two divorces never seemed to hurt him in a state mostly divided between Catholics and Baptists). But as he got older he lost the step ahead of the law he had maintained through constant investigations and scandals, and went off for eight years in the hoosegow at the age of 75 after a conviction for receiving bribes in connection with casino licenses.

It was an uncharacteristic stumble. Edwards ran for governor five times and only lost once: to conservative Democratic congressman Buddy Roemer in 1987 (Roemer finished first in the jungle primary, and Edwards, knowing he was beaten, withdrew from the runoff) when declining petroleum prices hammered state revenues and forced him to champion an unpopular tax increase. Four years earlier, he had won his third term in a decisive victory over Louisiana’s first Republican governor, David Treen; that campaign produced perhaps Edwards’s most famous (and most characteristic) quip: “The only way I can lose this election is if I’m caught in bed with either a dead girl or a live boy.”

But it was Edwards’s final comeback, in 1991, that solidified his position in national as well as state political history. His vanquisher Roemer had become a Republican at the beginning of his reelection campaign and proved incapable of heading off a challenge from former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke, who exploited white working-class economic and racial grievances. Thanks to a strong base among the Black voters who had always supported him, Edwards led the jungle primary field, trailed by Duke and Roemer, and for a good while polls showed Duke poised to pull off a shocking victory in the runoff. But a remarkable coalition that included Republican President George H.W. Bush (fearful of what a Governor Duke would do to the GOP’s image) and much of the state’s business community (fearful of what a Governor Duke would do to Louisiana’s economic-development prospects) got behind the tarnished but acceptable Democrat, who was able to raise enormous sums of money nationally. The conditional nature of conservative support for Edwards was summed up in one of the greatest bumper-sticker slogans of all time: “Vote for the Crook. It’s Important!”

But Edwards did play a key role in reminding voters about Duke’s real nature. Pollsters figured out that while conservative white Louisianans were willing to forgive Duke for his Klan association, they were shocked when exposed to images of him in full Nazi regalia as an attention-seeking grad student at LSU. During the one candidate debate late in the runoff campaign, Duke did his usual demagoguing about welfare dependency, and Edwards tartly responded that he had been working on welfare reform “when you were still goose-stepping around Baton Rouge.” The image of Duke wearing a swastika and giving the Hitler salute was central to the Edwards campaign in its final surge to a landslide win fueled by record Black turnout.

The 1991 “Race From Hell” wasn’t Edwards’s last hayride: In 2014, after his release from prison and his marriage to pen pal Trina Grimes, he ran for an open seat in Congress in a a heavily Republican district and finished first in the initial round over a huge field. He predictably lost the runoff, but it helped keep him in the public eye, along with a reality TV show called The Governor’s Wife featuring Trina and her aging husband.

Republicans are now the dominant party in Louisiana, and the current Democratic governor, John Bel Edwards (emphatically no relation to Edwin), owes much of his success to former Republican governor Bobby Jindal’s disastrous fiscal policies and his own anti-abortion views. The state’s political landscape is definitely more boring than it was in Ed Edwards’s salad years. But John Bel Edwards was present at the former governor’s 90th birthday party in Baton Rouge, at which the old rascal supplied, as always, the customary quip: “I’m 90 years old, and I woke up Friday and took my son to preschool.”

He will be missed.