The White House’s usual calculus was no longer cutting it by Monday night, a fact that was becoming undeniable with each new wave of desperate reports from Kabul.

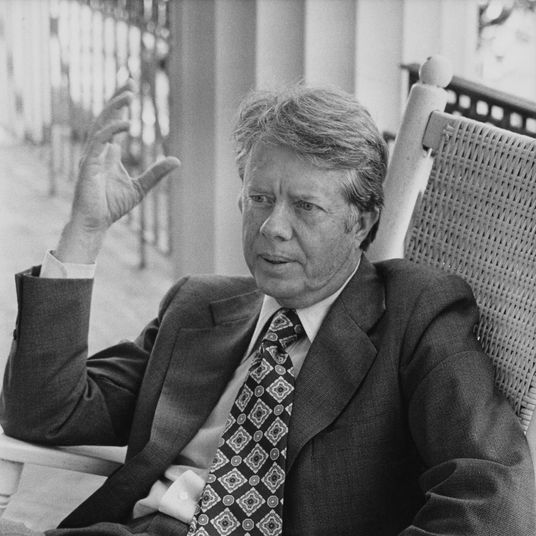

Gone were the weeks of internal administration debate, which were never really much of a debate. As president, Joe Biden had insisted, as he had for a decade, on full withdrawal from Afghanistan. As usual, he was facing pushback from the foreign-policy Establishment on this matter, including arguments from military leaders like Joint Chiefs Chairman Mark Milley and Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin to consider maintaining a residual force to keep the country stable, say people close to the conversations.

Then, for months, Biden, Austin, Secretary of State Antony Blinken, and Chargé d’Affaires Ross Wilson had both publicly and privately escalated pressure on Afghan president Ashraf Ghani — while Biden’s national security adviser, Jake Sullivan, leaned on Hamdullah Mohib, his counterpart in Ghani’s government — to articulate a military strategy, especially in cities vulnerable to Taliban advances, according to officials familiar with the campaign. And for months, say people who’ve been around Biden, he had been growing more frustrated with the Afghan government, his patience for it as thin as ever after nine-plus years of inconsistent engagement. All the while, his intelligence reports got grimmer over spring and summer and raised the prospect of a quick government collapse.

When Biden returned early to the White House from a long weekend at Camp David, he felt compelled to again explain the duty he felt to finally end the unpopular two-decade war, declaring: “I will not pass this responsibility on to a fifth president, I will not mislead the American people by claiming that just a little more time in Afghanistan will make all the difference.” By then, though, he was already late to explain why the American withdrawal had ended so jarringly, beyond the failures of the Afghan government, and he let the opportunity pass. It was a glaring omission: Not only had the Afghan government failed, Taliban rule had returned. With it came urgent questions about the American ability to evacuate locals who’d helped them on the ground for years.

It’s been nearly three years now that the people around Biden have been repeating like a mantra that the conversation on cable news and Twitter was divorced from political reality, and that the then-candidate, now-president had a better sense for what’s actually popular than any talking head. When it came to Afghanistan, that’s long meant ignoring the bipartisan Beltway “Blob” — the forever-hawkish foreign- and defense-policy Establishment that again popped up in repeated cable packages and newspaper reports over the last two weeks arguing for a never-ending American presence. Instead, he would plow along with a push to disengage. Said one person close to the White House on Wednesday of the coverage: “The modern press too often sacrifice objectivity for coverage, which omits serious consideration of the path not taken; distorts complex situations so they can be treated like a cheap game; and which gives disproportionate influence to the voices of affluent demographics they are personally familiar with. For example, in this case, they are elevating the Blob and its well-fed constituents who spent years lying to them about progress in Afghanistan in order to effectively advocate — despite being people who are supposedly impartial — for having sent more American service members into Afghanistan to fight and die to stop another Taliban offensive.”

Withdrawal is an outcome supported by a significant majority of the country after 20 brutal years, and Biden himself has been especially proud of that, particularly in the time since it became clear he would be the president to finalize the exit. “I stand squarely behind my decision,” he said on Monday. “After 20 years, I’ve learned the hard way that there was never a good time to withdraw U.S. forces.”

But the clarity of Biden’s goal and administration officials’ insistence that he faced a binary choice with one clear, popular option did little to explain the images of thousands of Afghans crowding onto the Hamid Karzai International Airport tarmac, desperate to get out. “Their calculation” — that Americans support withdrawal, no matter what the John Boltons of the world say on TV — “was correct,” one senior Senate Democratic aide close to the administration told me after Biden addressed the nation. “But once you’ve got images of people clinging to wheels of C-17s and falling to their deaths, that will linger.”

Only after Biden’s speech on Monday did this reality fully settle in at the White House. First, Biden authorized $500 million to support more visa applicants and other Afghans, such as interpreters, who’d helped American forces. Then aides girded for the kind of predictable but grim Washington blame game they once thought they could avoid: military officials blaming the State Department for not being prepared for chaos in Kabul; diplomats pointing at executive-office dithering over how to extract Americans; strategists wondering aloud about the quality of the intelligence on the Taliban’s strength; and the intelligence community inevitably leaking its top-line findings. “Contradicting Biden, Reports Warned of Rapid Collapse,” blared the New York Times’ front page on Wednesday. (“Suuure,” one person close to Biden eye-rolled to me later that morning. A senior intelligence official was, soon after, more diplomatic: “We consistently identified the risk of a rapid collapse of the Afghan government. We also grew more pessimistic about the government’s survival as the fighting season progressed. This was less an issue of Afghan military capabilities and more a reflection of Afghan leadership, cohesion and willpower. That said, the Afghan government unraveled even more quickly than we anticipated.”)

People close to Biden have spent recent days insisting they knew the final stages of withdrawal could get complicated — the National Security Council had met three dozen times on Afghanistan alone since Biden announced the withdrawal in April, said a senior administration official, and the White House led planning meetings in Kabul this summer that included simulations of evacuation scenarios. The State Department, meanwhile, sent nine travel and security alerts for the country between late April and mid-August. On Monday, the White House distributed talking points to lawmakers insisting: “The administration knew that there was a distinct possibility that Kabul would fall to the Taliban. It was not an inevitability. It was a possibility,” [emphasis original] according to a copy obtained by New York.

But those same talking points raised the ire even of Democrats supportive of Biden and the withdrawal. Of particular concern was a line claiming: “Many have asked why we did not evacuate more Afghanistan civilians, sooner. Part of the answer is that many did not want to leave earlier: Many Afghans to whom we gave visas to come to the U.S. chose to stay in their country, still hopeful.” There was a crush of Afghans trying to get out, and no one should have been surprised, these lawmakers say. Senate Intelligence Committee leaders Mark Warner and Marco Rubio had also sent the White House a letter a month ago urging quicker help for Afghans who’d helped the U.S. war effort. Many more representatives and senators with military or foreign-policy experience reported being suddenly slammed with requests for help. (“Anyone writing goddamn talking points should get on the visa line,” New Jersey Democrat Tom Malinowski told CNN.)

Undergirding some fellow Democrats’ frustration, in particular, is a fear that the administration is so worried about the possible political fallout ahead of next year’s midterms that they won’t admit enough refugees. On this front, the Vietnam comparisons that Barack Obama once banned from his administration’s discussions of Afghanistan have been ubiquitous. And while Biden’s aides insist he is on the right side of public opinion about ending the war, they are also largely careful to avoid saying he is thinking about the crass politics of a mass refugee resettlement. Still, some staffers in recent days have been sharing stories about how, in the words of my colleague Ed Kilgore, “the fall of Saigon didn’t end Gerald Ford’s presidency.”

Biden has, in fact, been thinking about the broader politics of a moment like this for over a decade. In 2019, the author George Packer reprinted a section from Richard Holbrooke’s diaries in Our Man, his book about the foreign-policy grandee. It recounted a 2010 conversation with Biden:

Joe took the position, plain and simple, that we have to get out of Afghanistan. I reminded him that the president and Hillary and indeed, I think, Joe himself had talked about a residual presence like Iraq, which he said he’d been working on most of the last year, that we would need congressional appropriations to train the army and the police and give economic assistance, we wouldn’t get any of that if women were sent back to the black years and the dark ages. He said it ain’t going to happen, he said I don’t understand politics, he said we’re facing a debacle politically, he said we’re going to lose the presidency in 2012 if unemployment remains high, and Afghanistan was the other issue that could pull us down and we have to be on our way out, that we had to do what we did in Vietnam.

This shocked me and I commented immediately that I thought we had a certain obligation to the people who had trusted us. He said, “Fuck that, we don’t have to worry about that. We did it in Vietnam, Nixon and Kissinger got away with it.”

After receiving reports from Kabul and watching national attention shift to the chaotic scene there on Monday, Biden returned from Camp David ahead of schedule with National Security Council chief of staff Yohannes Abraham, and gave his speech. He not only reminded Americans that he’d opposed counterinsurgency in Afghanistan since 2009, but insisted that it was his predecessor’s decisions that had laid the specific groundwork for this kind of withdrawal. Before leaving the White House and returning to the presidential retreat for one more night with longtime adviser Steve Ricchetti in tow, he issued a reminder. “When I came into office, I inherited a deal that President Trump negotiated with the Taliban,” he said. “The choice I had to make, as your president, was either to follow through on that agreement or be prepared to go back to fighting the Taliban in the middle of the spring fighting season.”

Even before Biden spoke, some Democrats tried laying the blame for the mess on the shoulders of Trump and his allies. Virginia representative Gerry Connolly, a senior member of the House’s Foreign Affairs Committee, tweeted: “Trump & Pompeo undermined the Afghan military and government by: 1. Agreeing to elevate the Taliban as a legitimate entity 2. Agreeing to exclude Afghan government from negotiations with the Taliban. 3. Agreeing to allied withdrawal by May 1. This tragedy is their doing.”

Still, as more scenes from the airport in Kabul hit cable news, frustration simmered as they couldn’t make this case more clearly: “There’s no good way to talk about it, and there’s no good way you can describe this as anything other than Afghanistan’s version of the fall of Saigon. It’s mortifying,” said a second senior Senate Democratic aide. “It’s what we’ve always wanted, to end this endless war, and it does seem like there are no Americans being threatened,” said a third. Now, he said, “Obviously everything else is fucking awful as shit. But what are we supposed to do? Stay there forever?”

This crowd was, finally, buoyed on Tuesday — first by news circulated by the White House that the airport in Kabul was ramping up evacuations again, and then by a conference call for Hill staff where administration officials revealed that they now expected to get one plane of evacuees in the air each hour.

Shortly before Biden returned to the White House from Camp David yet again on Tuesday night — this time joined by both Abraham and Ricchetti — people at the top of the administration appeared to be breathing slightly easier. At this point, I got Jake Auchincloss, a 33-year-old Massachusetts representative who served as a captain in Helmand Province in 2012, on the phone. “We’re talking about winding down a two-decade effort in a country whose moniker is ‘the graveyard of empires.’ The withdrawal was never going to be smooth sailing,” he said. “More salient to me than the horsepower of the Taliban advance or the firepower that wasn’t there from American close air support is the lack of willpower on behalf of Afghan security forces. Their cratering was the exemplar for why counterinsurgency could not compete in Afghanistan.”

This was Biden’s point, too, and by late Tuesday, people at the top of the administration appeared to be breathing slightly easier. The White House offered another update: They’d gotten 3,200 people out of the country, had moved 2,000 Afghans to the United States already, and were expecting the flow to accelerate.

No one, though, can fully exhale. There is still little clarity about how Americans elsewhere in Afghanistan can expect to get to Kabul for evacuation at this point. Before Biden returned from Camp David for a second time on Tuesday, Senate Foreign Relations Committee chairman Bob Menendez — a Democrat with Biden’s old job atop the panel — promised it would now “seek a full accounting” of “the Biden administration’s flawed execution of the U.S. withdrawal.” A few hours later, Nancy Pelosi said a House probe would focus on “the highest-level officials in the Biden administration.” It would start, she said, as early as next week.