America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan has yet to cost our nation a single casualty. Evacuations of U.S. citizens and allies from Kabul’s airport are proceeding at a faster pace than the White House had promised, or than its critics had deemed possible. Afghanistan’s decades-long civil war has reached a lull, if not an end. On the streets of Kabul, “order and quiet” have replaced “rising crime and violence.” Meanwhile, the Taliban is negotiating with former Afghan president Hamid Karzai over the establishment of “an inclusive government acceptable to all Afghans.”

In other words, Joe Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan has been a “disastrous” and “humiliating” “fiasco,” in the words of the mainstream media’s ostensibly objective foreign-policy journalists.

This may be an accurate description of what recent events in Kabul have meant for the president, politically. The latest polls have shown sharp drops in Biden’s approval rating, driven in part by widespread opposition to “the way” his administration handled its (otherwise popular) exit from Afghanistan. Yet this political fiasco is not a development that the media covered so much as one that it created.

The Biden administration made some genuine errors of contingency planning. It could have done (and should now do) more to facilitate the mass resettlement of Afghan refugees. But as far as conclusions to multi-decade wars go, America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan is thus far proceeding with relatively little chaos and tragedy. And it’s far from clear that the withdrawal could have been much more orderly had the White House only executed it in a better “way.”

It has long been apparent that America’s exit from Afghanistan would be tantamount to the Taliban’s victory. U.S. intelligence officials may have been excessively optimistic about the Afghan government’s staying power, but even they thought the government in Kabul would collapse within two years of America’s retreat. Simply put, there is no proud way to lose a war to a cult of heroin-dealing child rapists (especially when your side in that war featured no small number of men who fit a similar description). And there probably wasn’t a non-chaotic way of doing so, either. The Biden administration advised all U.S. civilians in Afghanistan to leave the country in May. Forcibly evacuating those who chose to stay, along with every Afghan ally who feared Taliban reprisals — before the Afghan government fell — would have been a Herculean task in terms of pure logistics. And it was an impossible task in terms of geopolitics: Before its collapse, the Afghan government had pressured the United States to limit its evacuation efforts, so as to avoid broadcasting the message that America deemed a Taliban victory inevitable. This was a reasonable concern. Few in the Afghan security forces were eager to die for a lost cause, which is one reason why the Taliban met weak resistance by the time it reached Kabul. Had the U.S. attempted to evacuate all its allies before the capital fell, the initial stages of that effort would have almost certainly expedited the surrender of the Afghan security forces and thus, left many Afghans who worked with the U.S. in the same basic predicament they find themselves in now.

All of which is to say: Ascertaining how much of the heartache in Kabul today derives from imperfections in Biden’s withdrawal plan — and how much would have occurred under any plausible U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan — is no easy task.

It is also a task that the media has felt no obligation to undertake. Mainstream coverage of Kabul’s fall and its aftermath has been anything but circumspect. Attempts to weigh the benefits of America’s withdrawal (e.g., the humanitarian gains inherent to the cessation of 20 years of civil war) against its costs have been rare; attempts to judge Biden’s execution of that withdrawal against rigorous counterfactuals have been rarer still. Instead, ostensibly neutral correspondents and anchors have (1) openly editorialized against the White House’s policy; (2) assigned Biden near-total responsibility for the final collapse of the proto-failed state his predecessors had established; and then (3) reported on the potential political costs of Biden’s actions, as though they were not actively imposing those costs through their own speculations about just “how politically damaging” the president’s failures of “competence” and “empathy” would prove to be.

Some manifestations of media bias have been overt. Declan Walsh, the New York Times’ chief Africa correspondent (a reporting position, not an opining one) tweeted shortly before the Taliban’s final victory, “Jalalabad gone, only Kabul left. For those who lamented ‘forever wars’ — is the phrase anything more than a comforting cop-out for epic failures of policy and the imagination? — here’s what the end looks like.” It is difficult to read that statement as anything but open advocacy against U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan, a policy supported by both the sitting president and a majority of the American public.

Meanwhile, Richard Engel tweeted Friday, “Biden says U.S. in constant contact with Taliban to get safe passage to airport. So, U.S. asking former enemy, the Taliban, to please allow us to get our people out while they take the country.” There were many ways that NBC News’ chief foreign correspondent could have characterized the news that Biden had secured the cooperation of Afghanistan’s reigning regime in the evacuation of U.S. citizens. He chose to portray it — dubiously — as a display of national self-abasement; in Engel’s account, Biden was “asking” an enemy to “please allow” Americans’ safe passage out of the country, as though the U.S. president were groveling at Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar’s feet, rather than threatening ruinous sanctions should harm come to U.S. nationals. This is the sort of commentary one expects from jingoists on right-wing radio, not high-ranking reporters at major networks.

At the same time, CNN’s chief foreign correspondent Clarissa Ward saw fit to present her own pessimistic hunches about the Biden administration’s future performance as established fact, reporting Friday, “I’m sitting here for 12 hours in the [Kabul] airport, 8 hours on the airfield and I haven’t seen a single U.S. plane take off. How on Earth are you going to evacuate 50,000 people in the next two weeks? It just, it can’t happen.” The U.S. evacuated about 21,600 in a 24-hour span between Monday and Tuesday; as of this writing, the U.S. has evacuated more than 82,300 people in the past 11 days.

The most audacious expression of the “straight news” media’s embrace of advocacy journalism may have come from CBS News’ White House reporter Bo Erickson, who chose to disseminate a poll showing Biden’s approval had sunk — as a majority opposed his handling of the withdrawal from Afghanistan — like so:

The media’s bias takes slightly subtler form in a Times dispatch from Kabul published Sunday:

Every death at the Kabul airport, every child with a teddy-bear backpack separated from a parent, every Afghan supporter of the United States who is marooned, reinforces the impression of an unplanned United States withdrawal that was too precipitous and based on a disastrous misjudgment of the capacities of the American- and NATO-trained government military forces. They simply melted away.

This piece is presented to readers as straight reportage, not an op-ed or even a “news analysis.” Thus, its author, Times Paris bureau chief Roger Cohen, doesn’t assert that every marooned Afghan ally reinforces the fact that the U.S. withdrawal was too precipitous; he merely asserts that it reinforces that impression. This is, of course, a thin scrim for concealing outright advocacy. Impressions are inherently subjective. Events in Kabul make no direct impression on Americans in Peoria, so Cohen is not describing something that exists beyond his own subjectivity. Rather, he is presenting his own personal impression (and/or the dominant impression among the Western journalists around him) as a disembodied, globe-spanning sense of Biden’s policy. When Cohen’s peers at CNN, NBC, and CBS do the same, the alchemy of mass media turns its subjective impression into what it purports to be: a neutral description of public opinion.

This is not to say that Cohen’s despair at the plight of Afghan translators is not well-founded, or that his opposition to Biden’s withdrawal is necessarily unreasonable. The point is merely that he is presenting editorial judgments as factual ones. In doing so, he is also opining without assuming the burdens of the op-ed columnist: to clearly state one’s thesis (e.g., “The swift collapse of the Afghan army and consequent chaos in Kabul proves that America’s withdrawal from Afghanistan was excessively rapid”); defend that thesis with evidence; anticipate opposing arguments (e.g., “The fact that the Afghan security forces had so little capacity after 20 years of training actually demonstrated the inevitability of the Afghan government’s collapse and thus, the imperative to avoid prolonging bloodshed in a war that was already lost”); and then to rebut those arguments.

I articulated my own substantive views on these matters last week (although I now think that I was a tad harder on the White House than available facts justified). Those views may bespeak the biases of a millennial progressive whose formative years were spent gawking at George W. Bush’s war crimes and reading Noam Chomsky’s lectures. I cannot always prevent my ideological commitments from blinkering my vision. But I can be transparent about those commitments, and test my biased intuitions against the rigors of reasoned argument.

The mainstream media’s most influential opponents of Biden’s withdrawal from Afghanistan refuse to do the same. This refusal may not be conscious. It can be hard to recognize one’s normative assumptions as ideological when those assumptions are commonsense among one’s peers. There is certainly some diversity of opinion within the broad universe of U.S. foreign-policy reporters. And nearly everything I know about the pitfalls of America’s occupation of Afghanistan I learned from the foreign correspondents of mainstream news outlets. Nevertheless, the widely shared ideological assumptions and personal experiences of elite U.S. foreign-policy journalists biased mainstream coverage of Afghanistan over the past two weeks. The consequent bias is neither liberal nor conservative. One might call it “imperial,” in a not wholly pejorative sense: It is a point of view that (1) assumes the U.S. can and should exert decisive influence over global events; (2) aims to lift Americans out of their parochial nationalism and into a cosmopolitan sense of moral obligation; and (3) privileges suffering caused by American inaction abroad over suffering caused by American military “engagement.”

We’ve already seen that first aspect of the bias in action: The presumption that the U.S. president has both the right and capacity to, in the words of the Times’ Peter Baker, “assert command over world events” is what allowed the mainstream media to condemn Biden’s withdrawal without scrutinizing counterfactuals. The second aspect of this bias — its missionary quest against the median American’s indifference to foreign affairs — can be gleaned from the media’s laudable attempts to put a face on the victims of the Taliban’s violence and misogyny, as well as its not-so-praiseworthy expressions of contempt for Americans who wish to bring their nation’s troops home. Personally, I find this element of elite foreign-policy journalists’ ideology partly congenial and beneficent; Americans’ widespread support for taking in Afghan refugees surely owes something to the humanitarian convictions and narrative gifts of the mainstream press. And yet, that press has ultimately fallen victim to its own parochialism. On Sunday, the great Times reporter C.J Chivers dismissed nefarious explanations for the press’s negative coverage of Biden’s withdrawal by saying, in a now-deleted tweet, “Maybe people who have worked with Afghans, and been helped and protected and welcomed by them for years or even decades, happen to give a shit about them? If these are motivations for outcry that you can’t understand, that’s on you.”

These are indeed humane and understandable motivations for using one’s influence as a “straight news” reporter to advance the cause of one interested party in a contested policy debate. But they are not justifiable grounds for doing so.

In mainstream coverage, the suffering of the U.S.–aligned Afghan translators — whom foreign correspondents have come to know as sources and friends over two decades of occupation — looms large. The suffering of the thousands of Afghan security forces and civilians who’ve been dying each year in a civil war that our government has the wherewithal to prolong but not to win, however, has been all but ignored.

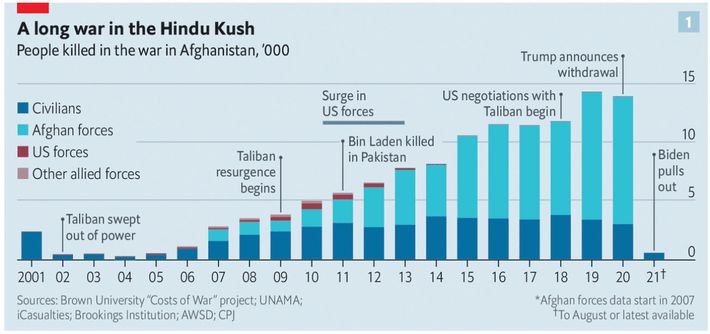

Countless reporters and commentators have cited the relatively low level of U.S. casualties in Afghanistan in recent years as proof that maintaining the status quo was a near cost-free proposition. When doing so, such cosmopolitan correspondents reveal the insularity of their moral vision. Before Biden commenced his withdrawal and the Taliban completed their victory, the 20th year of the war in Afghanistan was set to “witness the highest-ever number of documented civilian casualties in a single year” since the U.N. mission there began keeping records. Meanwhile, civilians unharmed by the war’s violence have endured “elevated rates of disease due to lack of clean drinking water, malnutrition, and reduced access to health care” as a result of the conflict, according to the Watson Institute’s “Costs of War” project. American involvement in Afghanistan has not only harmed civilians indirectly by perpetuating civil war; our nation also directly incinerated and tortured Afghans in the course of defending their freedom.

Every “child with a teddy-bear backpack separated from a parent” may reinforce the impression that America withdrew from Afghanistan too soon. Or every child killed in the course of a doomed counterinsurgency campaign may reinforce the impression that America withdrew far too late. It all depends on where one chooses to look.

The problem with the “imperial bias” of the media’s Afghanistan coverage is not that it has harmed Joe Biden’s approval rating. The problem is that it has compromised the Fourth Estate’s journalism and circumscribed its humanitarianism. One can reasonably argue that safeguarding the rights of Afghan women was worth the costs of prolonging armed conflict (costs that fell quite heavily on Afghan women). But one cannot reasonably leave those costs out of the discussion, or malign those who weigh them heavily as opponents of human rights. One can critically report on concrete failings in the Biden administration’s withdrawal plans. But one cannot presume Biden’s responsibility for every negative consequence that follows from ending a misbegotten war and deserve the title journalist. By privileging the victims of American military withdrawal over those of American military engagement — while presuming the U.S. president’s capacity to decisively shape events in foreign lands — the media has rendered itself objectively pro-war. In allowing personal attachments to dictate its humanitarian concerns, mainstream reporters have concentrated moral outrage on an injustice that the U.S. can’t resolve without resort to violence (the Taliban’s conquest of Afghanistan), while enabling mass indifference to a much larger injustice that the U.S. can drastically mitigate without killing anyone (the global shortfall of COVID-19 vaccines).

Until America’s bleeding-heart correspondents reckon with their field’s endemic biases, their reporting will routinely devolve into advocacy, if not rationalizations, for future bloodshed.