Established by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in September 2020, the federal eviction moratorium was designed to halt evictions due to missed rent because of surging unemployment and the reality that forced removals “threaten to increase the spread of COVID-19.” And while the more contagious Delta variant is spreading at an alarming rate throughout the United States, the protection expired at the stroke of midnight on Sunday, requiring hundreds of thousand of renters to pay back rent that accrued during the pandemic, or potentially face removal from their homes — and increased risk of being exposed to the virus. Below is a primer for the developing crisis, how it is affecting tenants whose income has been impacted by the virus, and how it may affect the pandemic.

What happens to tenants who owe back rent?

In addition to the rent due for August 1, tenants must pay any additional months they missed during the pandemic, except in states where extended protections are in place: Hawaii (August 6), Maryland (August 15), New York (August 30), Minnesota (September 12), California (September 30), Washington (September 30), and New Jersey (the official end of the public-health emergency designation plus two months). Several federal agencies — including the Federal Housing Finance Agency, the Department of Agriculture, the Department of Housing and Urban Development, and Veterans Affairs — have also extended their moratoriums until September 30. Renters in many states are also required to pay late fees for payments they have missed.

While it’s difficult to determine how many Americans could lose their homes, according to a U.S. Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey conducted on July 5, around 3.6 million people said they could face eviction in the next two months. Another recent survey by the Census Bureau found that an estimated 11 million adult tenants are considered seriously delinquent on rent.

Courts throughout the United States could be hit with a large number of eviction filings in the early days of August. Meanwhile, some 450,000 eviction cases have already been filed since the beginning of the pandemic in March of last year — cases that could now move more quickly through the courts because they are already in motion.

What are the Biden administration and Congress doing to address the crisis?

Following a 5-4 Supreme Court ruling in June — which barred the CDC from further extending the ban without a bill passed by Congress — the Biden administration requested last Thursday that lawmakers approve a one-month addition to the moratorium. “Really, we only learned about this yesterday,” Speaker Nancy Pelosi said last Friday. Frustrated by the short notice, Democrats were not able to pass the bill through the House in time. And while the eviction process began ramping back up on August 1, that date marked the beginning of vacation for representatives, whose recess lasts through the entire month. Shortly before the order expired, President Biden ordered the federal agencies mentioned above to extend eviction and foreclosure moratoriums until the end of September.

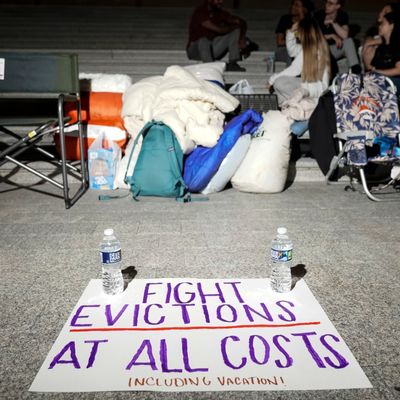

To protest against the failure to extend the moratorium, Missouri representative Cori Bush — who has faced evictions and homelessness prior to her time in office — slept on the steps of the Capitol. While encamped there, she urged Congress to reconvene “to reinstate the eviction moratorium to put an end to the eviction emergency.”

And while lawmakers have secured $47 billion for relief as part of the Emergency Rental Assistance program, logistical issues have resulted in only about $3 billion of the funds actually being distributed to around 600,000 tenants.

How might the end of the moratorium affect the pandemic?

Just as the Delta variant has upended many of the pandemic calculations made earlier this year, the plan for the moratorium to expire, with widespread vaccine access significantly slowing the spread of the virus, has been frustrated by the recent surge in cases. In the past seven days, cases have shot up by 53 percent to a daily average of 66,606. (Showing the effectiveness of vaccines to prevent serious cases, hospitalizations are up 31 percent and deaths just 8 percent.) But as Dr. Anthony Fauci warned on Sunday, “things are going to get worse” before the Delta surge collapses in the U.S.

If evictions move forward in large numbers, it’s possible that travel associated with moving, increased reliance on shelters, and more family members living in close quarters could increase the risk of transmission for those who have been forced from their home for failing to pay back rent. Just because the federal moratorium has expired, it does not mean that the science behind the CDC’s determination that evictions can spread COVID has lapsed with it.