A president’s legacy is rarely defined by any single legislative defeat. Barack Obama failed to shepherd climate legislation through Congress, but that did not stop him from passing a landmark health-care law. Donald Trump couldn’t repeal Obamacare, but he still secured a historically large corporate tax cut.

Joe Biden may have less room for error.

The president is on the cusp of achieving the largest expansion of the American welfare state in many decades, the largest investment in climate-change mitigation in U.S. history, the first pro-union revision to American labor law in a generation, drug-pricing reforms that eluded his Democratic predecessors, a large progressive tax increase, bipartisan infrastructure investments, a major expansion of public education, and much else besides.

And yet: The fate of all these measures rests on the passage of a single solitary bill.

This bizarre circumstance is the product of arcane Senate conventions, thin Democratic majorities, and blue America’s unfavorable odds of retaining Congress past 2022. Moderate Senate Democrats are committed to preserving the legislative filibuster, which has established a de facto 60-vote threshold for the passage of major bills. But there is one big exception to that rule: Once every fiscal year, Senate majorities can pass a single package of measures that concern the federal budget without having to overcome a filibuster. For this reason Democratic leaders have been forced to stuff the bulk of their party’s partisan priorities into one $3.5 trillion bill.

Then, the thinness of Democratic congressional majorities forced the party to put even more eggs into that basket. Biden was able to strike a bipartisan infrastructure agreement with a critical mass of Senate Republicans. But House progressives have enough votes to kill that bill — and have threatened to do so, unless their moderate co-partisans vote for the $3.5 trillion “Build Back Better” bill first. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi has endorsed the progressives’ demand, declining to hold a vote on the bipartisan bill until the bigger legislation is ready. The gambit here is straightforward. In order to squeeze Biden’s agenda through narrow congressional majorities, Democratic leaders are forcing their members into a binary choice: Support all the president’s priorities or none of them.

This is a risky play. And in different political circumstances, Democrats might be charting a less dicey course. If the party expected to expand its majorities next year, then it could knock out a flurry of (relatively) small-bore reforms that moderates and progressives unequivocally support. But that is not the party’s expectation. Presidents almost always lose seats in midterm elections, and this year redistricting will give Republicans further advantage. For this reason, Democrats are extremely likely to lose the House come 2023. Meanwhile, the GOP’s dominance in rural areas, which are heavily overrepresented in the Senate, means that some Democratic analysts believe the party will not reclaim full control of government for a decade following next year’s likely defeat. It is therefore difficult to pacify Democratic interest groups by telling them, “We’ll get to your thing next time.”

If this “now or never” ethos has led Democrats to bet Biden’s legacy on one reconciliation bill, it has also made negotiations over the precise size and shape of that bill exceptionally contentious.

The biggest division among congressional Democrats lies, of course, between progressives and moderates. The former view the reconciliation bill’s $3.5 trillion price tag as a compromise; many of the latter see it as exorbitant. Over the weekend, Joe Manchin vowed to vote against a $3.5 trillion bill, citing concerns about the impact of such spending on the deficit — or, if financed by tax increases, the competitiveness of America’s corporate sector. Bernie Sanders, for his part, threatened to vote against the Manchin-brokered bipartisan infrastructure deal if the West Virginia senator does not fall in line. If neither of these senators blink, Biden’s legacy will drastically shrink.

As House committees have begun drafting the fine details of the reconciliation bill, however, it’s become clear that “progressives versus moderates” is only one of several divides within the Democratic ranks. And some of these divisions complicate popular narratives about blue America’s burgeoning civil war.

Here is a quick rundown of three under-discussed, intra-Democratic divides that threaten to derail the Biden presidency:

Moderates who fear public opinion versus moderates who fear private power.

In the traditional narrative, moderate Democrats craft policy with an eye toward pleasing the median voter while progressives tailor legislation to the tastes of the ideological fringe. It isn’t hard to find contexts in which this dynamic prevails (e.g., on the issues of decriminalizing illegal border-crossing, defunding the police, and extending voting rights to the incarcerated, Congress’s most progressive members side with a minority of U.S. voters). But as I’ve written many times before, it’s just as easy to find instances in which self-styled centrists put ideological purity (and/or plutocratic prerogatives) above popular opinion.

The present fight over the reconciliation bill has produced some textbook examples.

Not every provision in the reconciliation bill’s framework enjoys overwhelming public support. So, one might expect ruthlessly pragmatic centrists to oppose a few of Biden’s least-loved provisions, if only to demonstrate their relative moderation to swing voters. In actuality, however, the party’s most disagreeable moderates have taken aim at the president’s most popular ideas.

On Monday, the Ways and Means Committee unveiled a draft proposal for empowering Medicare to negotiate drug prices with insurers. A Kaiser Family Foundation poll taken in June found that 88 percent of voters approve of that policy; among Republican voters, support stood at 77 percent.

The political utility of using Medicare’s buying power to force down drug prices goes beyond its congenial poll numbers. In addition to being ideologically palatable to the median voter, drug-price reform is also (1) salient to a high-turnout voting bloc (senior citizens); (2) anti-inflationary; and (3) a “payfor” that can be used to offset other spending. According to The Wall Street Journal’s Richard Rubin, the drug-price reforms in the House Ways and Means Committee’s draft proposal would yield an estimated $700 billion in government savings (a de facto tax on price-gouging drug companies).

Nevertheless, House moderates have mobilized in opposition to the policy. On Friday, Representatives Scott Peters and Kurt Schrader introduced a watered-down version of the leadership’s drug-pricing proposal. Under their scheme, Medicare would only be allowed to negotiate over the price of drugs that are not under patent and that lack market competition. In other words, it would allow Medicare to crack down on generic-drug monopolies, but forbid it from forcing more widespread deflation in the pharmaceutical sector. In May, some moderates took an even more reactionary stance, vowing to vote against any drug-pricing reforms that lacked bipartisan support in Congress.

Not all moderates are indifferent to the popularity of drug-pricing reform. In July, a group of “frontline” Democratic House members — lawmakers whose districts are, on average, more red than blue — demanded that such a policy be included in the reconciliation bill.

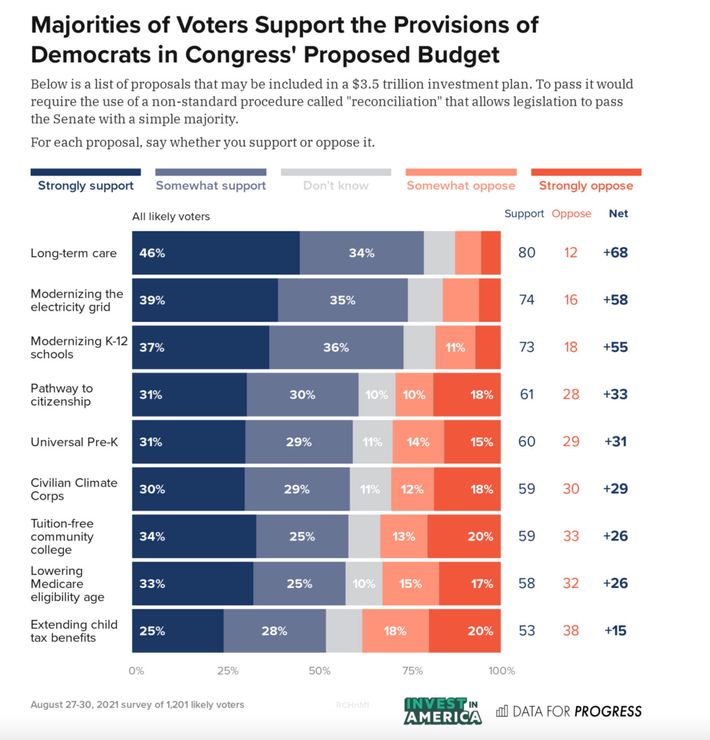

A similar dynamic has surfaced on the issue of long-term care for the elderly. Biden has proposed investing $400 billion into such care, so as to both boost the wages of home health aides and clear the Medicaid waiting list for at-home care. In August, the progressive firm Data for Progress (DFP) polled a long list of provisions in the reconciliation bill. None attracted more support than long-term care for the elderly.

And yet, Joe Manchin has reportedly named long-term care as one of the provisions he wants to cut most, despite the fact that West Virginia is the third-oldest state in the nation. Meanwhile, consummate House moderate Conor Lamb has been a leading proponent of the policy.

These divides highlight the limits of the catchall term “moderate Democrat.” As Matt Yglesias has observed, there are many different ways for lawmakers to pursue political safety. Catering to public opinion is one; nullifying threats to business groups with big pockets — such as the pharmaceutical industry or a chamber of commerce that’s less worried about elder care than inflation — is another. On several key questions, the reconciliation bill has split moderates who favor the former strategy from those partial to the latter.

In its draft text Monday, the House Ways and Means Committee appeared to split the difference between them on the issue of drug pricing: Although the committee’s proposal would empower Medicare to negotiate prices, the government would not attain that power until 2025. The point of this phase-in is unclear as of this writing. But if one were trying to secure the projected revenue that drug-pricing reform provides without alienating the drug-company stooges in one’s caucus, this might be a logical end point. The CBO scores proposals based on their expected budgetary impact over ten years. So starting the program in 2025 still gets you a decent chunk of change. Yet it also helps pro–Big Pharma Democrats vote for the reconciliation bill, secure in the knowledge that their favorite lobby will have plenty of chances to kill the proposal before it actually takes effect.

Bernie Sanders versus Nancy Pelosi.

For the most part, the Democratic Party’s leadership and its left flank have been working hand in glove on the reconciliation bill. But there is one notable conflict. And it’s one that doesn’t map that well onto traditional ideological battle lines.

If Senate Budget Chairman Bernie Sanders had his druthers, the reconciliation bill would have a $6 trillion price tag. But he agreed to a $3.5 trillion budget resolution after securing a promise from Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer: The final legislation would include $380 billion for adding hearing, vision, and dental coverage to Medicare.

But Democrats are struggling to find the fiscal space necessary for both Sanders’s ambitions for Medicare and Nancy Pelosi’s vision for the Affordable Care Act. And that’s put the two octogenarian reformers into tension. As the Washington Post reports, the democratic socialist sees improving Medicare as a potential capstone to his long career fighting for high-quality public-health insurance in the United States. Pelosi, meanwhile, wishes to fortify the ACA, a program she did more than anyone to bring into law. Alas, since the budget for the reconciliation bill’s health-care provisions is finite — and moderates are liable to force some cuts to that budget — there likely won’t be enough funding for both lawmakers’ priorities.

The Post characterizes this conflict as one between “a liberal faction that has pushed for a system in which the government, not insurance companies, provides health coverage” and Pelosi’s more moderate contingent of ACA defenders. But the substance of the dispute doesn’t fit that seamlessly into a conventional “progressive versus moderate” frame.

After all, Sanders supports beefing up ACA subsidies, and Pelosi backs expanding Medicare beneficiaries’ benefits. The issue is just one of priorities. And the Vermont senator’s priority is to enhance the health-insurance benefits that a disproportionately middle-class constituency currently enjoys, while Pelosi’s is to extend publicly subsidized health insurance to Americans who presently lack any decent coverage option (because they earn too much to qualify for Medicaid or ACA subsidies, but too little to afford quality insurance on the private market). Sanders’s priority is likely the better political play, as it would benefit a much larger and more politically engaged voting group. And expanding benefits via Medicare is also more cost-efficient than doing so through the ACA’s Rube Goldberg mechanism of subsidizing the purchase of private insurance. Still, it’s not obviously more progressive to prioritize improving Medicare benefits over making some form of basic health coverage affordable for Americans who do not currently qualify for any form of subsidized insurance.

It’s perverse that these two objectives have been put into competition. In Sanders’s ideal world, of course, Medicare would be extended to everyone. In the world we live in today, though, the democratic socialist is reportedly prioritizing the popular, cost-efficient health-care initiative, while the establishment Democrat is arguably prioritizing the more distributionally progressive one.

At the moment, Democrats appear inclined to give each lawmaker a half-loaf. The Ways and Means Committee’s proposal this week scaled back the cost of Medicare expansion by delaying the implementation of dental coverage until 2028.

The SALT caucus versus everyone else.

Finally, there is the divide between Democrats who want to slash taxes on affluent property owners in deep-blue states and … everyone else in the party.

To help offset the cost of their corporate tax cut in 2017, Republicans put a $10,000 cap on the amount of state and local taxes that Americans can deduct from their federal tax bills. The cost of this change fell overwhelmingly on high-income individuals in blue states, which tend to have higher property and income taxes than Republican ones.

In the 2018 midterms, Democrats were able to capitalize on the ensuing backlash: In New York, New Jersey, and California, affluent, historically Republican suburbs broke for Democratic candidates who promised to reverse Trump’s dastardly increase to their cost of living.

Now, a 30-member SALT caucus is threatening to vote against the reconciliation bill unless it includes relief for their states’ long-suffering, single-digit millionaires.

If fiscal space weren’t precious, progressives might be inclined to indulge this demand (in fact, some very left-wing lawmakers support its repeal). Since the SALT cap insulates the wealthy from high state-level taxes, it arguably makes it easier for Democrats to implement state-level social-welfare programs without incurring backlash.

But as we’ve seen, fiscal space is tightly limited. In deference to their caucuses’ deficit phobia, Democrats have been searching for politically palatable ways to offset $3.5 trillion worth of spending. The Ways and Means Committee could only come up with about $2.9 trillion worth this week. Add a full repeal of the SALT cap to the reconciliation bill, and its tax changes would only net Democrats $2.5 trillion in net revenue.

Thus, progressives oppose SALT cap repeal because it threatens to suck funding out of climate and social-welfare spending. And corporate Democrats who represent low-tax states have no stake in fighting for the policy. Yet the SALT caucus sees the policy as an existential priority. Absent the cap’s repeal, they believe that their high-tax states will struggle to compete for capital investment and high-skill labor, while they will personally struggle to compete for reelection.

As of this writing, it sounds like the Democratic leadership will try to pacify this contingent by raising the cap instead of repealing it completely. Yet to do so, it will become even more difficult to bridge all of the party’s other divides.

Democrats will need to find some way of closing those chasms — or else, Joe Biden’s legacy will fall right through them.