This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

Over the course of what must have been several uncomfortable days for her in the summer of 2017, Elizabeth Holmes sat in a San Francisco conference room and answered questions asked by lawyers from the Securities and Exchange Commission. They were deposing her about her actions as the founder and CEO of Theranos, the once-lauded start-up that unraveled in spectacular fashion following a Wall Street Journal investigation revealing that it had lied to the world about its progress for years on a blood-testing technology.

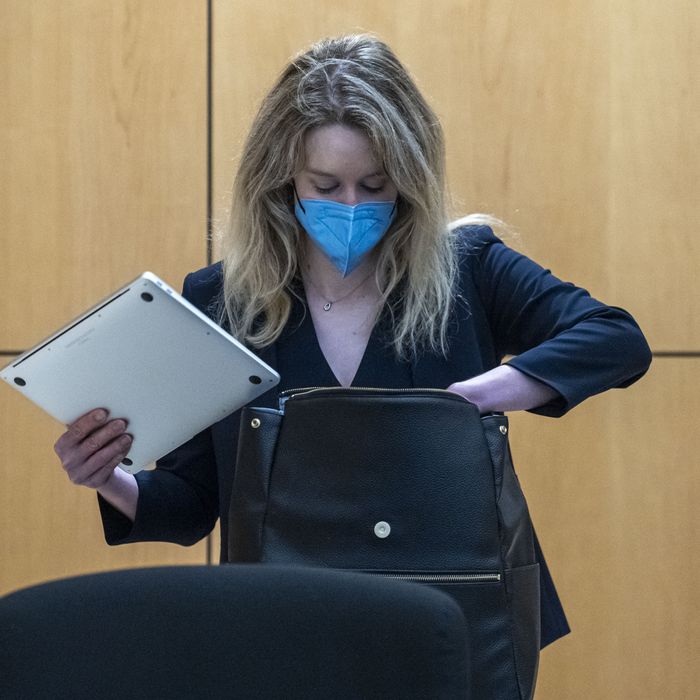

In the deposition, Holmes attempted a transformation. She had ditched the black turtleneck that had once been her trademark (one that she had lifted from Steve Jobs) and wore more federal-investigation-appropriate attire — a collared, button-down shirt under a jacket. More ambitiously, Holmes, who had been the face of Theranos, claimed that she had not, in fact, been responsible for entire swathes of the company’s operations — its sales force, its financial projections, its pitches to investors, or its relationships with its largest customers, which, at one time, included Walgreens and Safeway. When asked about some of the company’s projections for its Walgreens business, Holmes said, “I don’t know what was behind these numbers and this model.” On another day, Holmes was asked about how other lab companies drew blood and answered, “I don’t know what other blood companies use,” seemingly indifferent to the notion that she might actually know what her competition was doing. At one point, following a series of answers from Holmes in this vein, a lawyer for the SEC asked, incredulously: “So what were you responsible for?”

It was not a successful strategy for Holmes four years ago — she ultimately settled with the agency for $500,000. But it is nonetheless one that she is likely to repurpose over the course of a federal criminal trial on wire fraud charges that begins in earnest this week in San Jose. In the days leading up to jury selection, previously sealed court records revealed that Holmes may attribute her involvement in the Theranos debacle to a decade-long, allegedly abusive relationship with her onetime boyfriend Ramesh “Sunny” Balwani — also the company’s president and chief operating officer, who is scheduled to go on trial separately early next year — and that she will likely take the stand in her defense. The trial is the latest chapter in a remarkable story — the cinematic rise and fall of Holmes — that has played out in unusually public and entrancing fashion over the better part of a decade, and that has proved a seemingly endless source of fascination for the media and public alike.

The peculiar alchemy that creates a trial of transcendent public interest is unpredictable — after all, recent criminal prosecutions of health-care executives whose conduct was at least as bad, if not significantly worse, have drawn little attention. When it happens though, it tends to be when the underlying events provide a dramatic stand-in for a broader public debate. This is definitely not the O.J. Simpson prosecution in the scale of its public reach and engagement (I watched the jury deliver its verdict live in a packed school library at the time). But much like that case seemed to encapsulate questions about race and policing in the 1990s, the Holmes prosecution seems well-positioned to provide a forum in miniature on a few big questions of our moment: on the limits of ostentatious fakery in public life; on the seeming immunity of the rich and powerful to criminal punishment for even the most flagrant misdeeds; and on the dubious abilities of our nominally elite classes — including major media outlets, wealthy investors, government officials, and white-collar lawyers — to competently mediate the difference between artifice and reality.

Before the fall, Holmes and Theranos offered a deceptively simple pitch: that the company had developed technology that would allow hundreds of varieties of medical tests to be run from a few drops of blood taken from a fingertip. Holmes founded the company in 2003 as a 19-year-old student at Stanford, and by 2015, Theranos was offering its services at walk-in clinics in some Walgreens stores while claiming that its proprietary box might ultimately be placed in people’s homes. The premise — that widespread self-testing would be a net positive for the health-care system — was itself dubious, but that turned out not to matter much.

Holmes obtained hundreds of millions of dollars in investments — from Betsy DeVos’s family, the Walton family, Rupert Murdoch, Carlos Slim, and Robert Kraft, among others — using a preternatural skill for ingratiating herself to and impressing powerful people. The company’s board of directors included a roster of prominent former government officials — among them former secretaries of State George Shultz and Henry Kissinger, former secretary of Defense William Perry, former U.S. senators William Frist and Sam Nunn, and Jim Mattis, who would become Trump’s Defense secretary. (They all shared an affiliation with the conservative Hoover Institution, a think tank with an ill-defined relationship with Stanford.) The company’s valuation would eventually reach $9 billion.

In the process, Holmes herself become a public icon — the result of some undefinable combination of the appeal of Theranos’s ambition (in theory, democratizing health care and providing people with greater control over and knowledge of their health), her telegenic and self-assured presence, her anointed status as “the youngest self-made female billionaire in the world,” and, perhaps most importantly, a self-reinforcing loop of attention from elite media outlets and public figures. There was — among many other examples — a now-infamous cover story in Fortune, a Q&A with Holmes in the Journal’s opinion section, a flattering profile in the The New Yorker, and a slew of media distinctions that reside somewhere in the space between actual journalism and advertiser-friendly gloss.

In 2015, Barack Obama selected Holmes as an Ambassador of Global Entrepreneurship, and she attended a state dinner at the White House with the prime minister of Japan. During a visit of one of Theranos’s facilities, then-Vice-President Joe Biden called it a “laboratory of the future.” Later that year, Holmes spoke onstage with former president Bill Clinton at the annual meeting of the Clinton Global Initiative.

In fact, things had already begun to unravel in February of that year, after John Carreyrou, then a reporter at the Journal who had just read The New Yorker’s story, received a tip from a source who was skeptical of what Theranos had been saying. In October, Carreyrou published the first in a series of stories that systematically dismantled the company’s claims. As it turned out, the company actually relied on standard intravenous draws and commercially available machines to run most of its tests, while its proprietary technology handled just a small number of them — and not well. Shortly after the article came out, Holmes and Balwani convened a company-wide meeting during which Holmes claimed that the story was inaccurate and rallied her employees. At one point, the group chanted, “Fuck you, Carreyrou!” in unison. But that defiant spirit could not stave off what was to come. Investigations by the SEC and the Department of Justice followed, and the company eventually voided two years of results from its device. In June 2018, the government indicted Holmes and Balwani. Theranos dissolved later that year.

Holmes’s fall has provided just as much media fodder as the rise. Carreyrou went on to publish a widely praised book — a page-turner that provides remarkable details about Holmes and the company (at one point, she enlists Mattis to tamp down concerns about the company’s compliance with federal regulations), as well as their efforts to stop Carreyrou’s reporting (among them an unsuccessful attempt to personally lobby Murdoch to kill the story). Alex Gibney produced a documentary for HBO, ABC News produced a podcast, and a movie and television show are in the works. Carreyrou himself just launched a podcast that will follow the trial.

I asked him what it felt like to see Holmes’s case head to some sort of resolution after all this time. He expressed “relief that we’re finally getting close to this denouement.” “This thing has gobbled up six years of my life,” he told me, and “a small part of my life has been in limbo as a result.” He went on to acknowledge that he is “supposed to be objective as a journalist,” but said that he would like to see her “answer for her wrongdoing” and hopes that “justice is served.”

Holmes’s case wound up in the hands of prosecutors in the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California — home to Silicon Valley and Theranos before its demise. The judge has set aside four months for the trial, with three trial days a week. The parties have identified upward of 250 witnesses.

This might suggest a bit of a slog or circus, but the government’s indictment — a very general road map for the trial — is an unusual model of prosecutorial reserve, clarity, and concision, all the more so since the risk of prosecutors performing for media attention in a high-profile case is not insignificant. The core of the indictment runs just ten pages and alleges that Holmes and Balwani engaged in two different schemes: one to defraud Theranos’s investors and the other to defraud Theranos’s patients. The government claims that the two made a variety of misleading statements about the company’s technology and operations to their investors — most notably, that Theranos’s proprietary analyzers actually worked, and that the company was using them to perform its tests. The alleged scheme to defraud Theranos’s patients is premised on the company’s claims that they could provide — as the government puts it — “accurate, fast, reliable and cheap blood tests and results.”

Based on these allegations, the indictment charges Holmes and Balwani with 12 crimes, each counts either of wire fraud or conspiracy to commit it. The crime of wire fraud is essentially a scheme to obtain money or property from someone else through the use of materially false or misleading statements that also involves so-called “interstate wires,” which can be pretty much any kind of electronic communication from a phone call to an email to a bank transaction. The conspiracy, of course, is just the agreement — even an informal one — to commit that act.

In this case, the two conspiracy counts and the ten substantive counts are based largely on the same core conduct, but they offer a bunch of distinct pathways to a conviction for the government. It is clear that prosecutors intend to prove that Theranos’s business model was essentially a fraud — that they had not revolutionized blood testing and were nowhere close to doing so, despite having rolled out their services to the public. But if, for instance, all that they manage to do is convince the jury that Holmes and Balwani misled investors about Theranos’s relationship with Walgreens — that it was supposedly “expanding,” when, in fact, it had “stalled,” as the indictment alleges — that could yield multiple guilty verdicts by itself.

The various counts in the indictment also allow prosecutors to tell different parts of the Theranos story. Three of the government’s wire fraud counts, for instance, relate to results received by three different patients, each of whom will take the stand. This is testimony that a jury is likely to find highly sympathetic, and that Holmes fought vigorously — and unsuccessfully — to prevent. Ultimately, prosecutors plan to present testimony from approximately 11 patients who received faulty results, along with nine treating physicians.

The list of other potential witnesses includes some intriguing possibilities — among them Kissinger, Mattis, Frist, Nunn, and Murdoch. Onetime super-lawyer David Boies, who represented Theranos using some rather unseemly tactics — including threatening to sue former employees who spoke out against Theranos — could also land in the witness box. Whether these people will actually testify remains to be seen, but they are likely to be far less important to the government’s case than former employees who could actually describe how Holmes may have lied about the business. Some of those people have already spoken with journalists — like George Shultz’s grandson Tyler, a former employee at the company who was a crucial first source for Carreyrou and who went on to rack up more than $400,000 in legal fees dealing with Boies’s team — but others have not. For instance, Kingshuk Das, who oversaw Theranos’s lab in its last years, told the government that the machines did not meet the standards for clinical testing.

Holmes and Theranos’s interactions with federal regulators will also be an important part of the government’s case. Prosecutors intend to present the results of an inspection in late 2015, conducted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, that concluded that Theranos had violated a number of legal requirements and posed “immediate jeopardy to patient health and safety,” as well as earlier, more limited reports identifying possible violations by the Food and Drug Administration and the California Department of Public Health.

Holmes’s lawyers have tried to call the integrity of the federal inspections into question on the theory that they were improperly motivated by negative press coverage. But even if this were true, it is hard to envision a jury caring much.

If anything, the question that jurors are likely to have — one, at least, that I had — is why federal regulators did not catch on to Theranos’s problems earlier, given the brazenness of the alleged scheme, the heavily regulated nature of the medical industry, and the considerable stakes of erroneous blood testing. When I posed this question to Lars Noah, a law professor at the University of Florida who specializes in the regulation of pharmaceuticals and medical devices, he likened it to how the Internal Revenue Service can only test the veracity of a small number of tax returns through audits, adding, “I don’t think there were any real red flags early on where CMS missed an opportunity to come knocking.” In this case, the government’s absence appears to have had more to do with a broader failure to fund critical federal services than a unique government oversight — which is perhaps even more disturbing than a discrete lapse.

There is, of course, a deep irony to Holmes’s effort to blame the media for government agencies’ intervention, considering just how important her courting of the press was to the ascendance of Theranos and Holmes in the first place — a story that will itself be on display during the trial. The government intends to call Roger Parloff, the author of Fortune’s laudatory 2014 cover story on Holmes, as well as Dr. Eric Topol, who published an interview with her in November 2013 at the website Medscape. And it will present the jury with Ken Auletta’s profile for The New Yorker. All three men have been admirably reflective about their work since the Theranos story unraveled, though media critics have generally not been kind to these and similar pieces from that period. (Vanity Fair described “the Silicon Valley tech press” and its coverage of Theranos as “one of the more insidious culprits” in the company’s rise.)

The trial may provide some mitigation, if not exactly exoneration, for those who took the bait on Holmes’s story. The government has said that it will show how Holmes and others at Theranos used the media to disseminate false claims about the company’s technology. Likewise, Carreyrou, who has emerged as something of a journalistic hero at a time when public trust in the media is at record lows, told me that he had gotten to know both Parloff and Auletta and thought they were “terrific guys” who “were just misled and lied to,” and that a lot of the criticism amounted to “schadenfreude.” Indeed, Carreyrou credits Auletta — whose piece did, in fact, have some notes of skepticism about the lack of peer-reviewed studies to validate Theranos’s claims at the time — with getting “a lot closer to calling her bullshit” than people realize and said that his podcast will explore how Auletta’s work “opened the door for me.”

To address this, Holmes’s lawyers have said that they will show that it is not unusual for start-ups to use exaggerated claims to attract investments and media attention. You would not be wrong to think that this sounds like a defense of lying, but it is a variation on a common defense strategy in white-collar prosecutions that appear to be the first of their kind in a particular economic sector or market — that lots of people were engaged in the sort of conduct at issue, and that everyone in the market knew it.

Sometimes this works. Several years ago, a former Barclays foreign-exchange trader persuaded a judge to throw out his case in the middle of the trial on the theory that his alleged misrepresentations could not have been “material” — a necessary element of a wire fraud charge — since everyone in the market was effectively “BS-ing” each other. (While at the Justice Department, I worked on that investigation for a few months near its inception, but I was not involved in the decision to bring the charges or in prosecuting the case.)

This would be harder for Holmes to pull off, given the number of alleged misrepresentations at issue and their significance. Megarich investors tend not to be a particularly sympathetic lot, and the jury’s sympathy for their plight may be limited, which is why the government’s patient-related charges are crucial. But at least as a legal matter, the government can establish the materiality of these misstatements if investors — including potentially Murdoch and DeVos’s son Rick, who is also on the witness list — take the stand and persuasively explain that they expected the truth from Holmes and Theranos, and that the truth would have affected their decisions to invest.

All of this suggests that Holmes, like most federal criminal defendants, faces an uphill battle. About 85 percent of all federal criminal cases — and about 90 percent in the subset of fraud cases — result in a conviction, though the Justice Department has fared worse in its highest-profile prosecutions. A recent analysis by the Journal put the conviction rate in Wall Street cases at about 80 percent. When things go wrong, they tend to do so in rather spectacular fashion — still, in any given federal criminal trial, the likely outcome is a conviction.

In the weeks leading up to jury selection in Holmes’s trial, there was a good deal of justifiable speculation about whether Holmes would take the stand in her own defense, which seemed like an unambiguously bad idea by standard legal thinking. It is unusual in any criminal prosecution for the defendant to testify, but one significant impediment for Holmes in particular is the voluminous public record of statements that she has already given in the form of media interviews and other taped appearances, which create an unusually large reservoir of material with which prosecutors can cross-examine her if she takes the stand and tries to distance herself from certain assertions or suggest that she did not understand what she was doing.

Holmes’s answers over the course of her SEC deposition also seemed to lock her in to some eyebrow-raising positions that she could not easily abandon. While discussing Parloff’s Fortune story, for instance, Holmes attempted to defend the various misrepresentations about the company’s work by arguing that her claims reflected the company’s “aspirations” rather than its “operations” — in other words, not the company’s technology as it actually existed, but what they hoped that they would one day achieve. “At that time, I did not think about it in the context of describing the operations of the company,” she said, in an assertion that is as hard to believe as it sounds. More broadly, Holmes’s repeated claims that she did not remember key events and did not know important facts seem to foreclose the option of taking the stand and suddenly recalling exculpatory details.

That assessment got even murkier with the revelation that Holmes’s lawyers may claim she was the victim of an alleged “abusive intimate-partner relationship” with Balwani, in which he subjected her to psychological, emotional, physical, and sexual abuse for “over a decade” that, in turn, led to post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, and anxiety. According to court filings, Holmes has claimed, among other things, that Balwani controlled what she ate and how she dressed; that he monitored her calls, texts, and emails; and that he threw what are at one point described as “hard, sharp objects at her.” In addition to providing expert testimony on the subject, Holmes’s lawyers said that she is “likely to testify herself to the reasons why she believed, relied on, and deferred to Mr. Balwani” in order to demonstrate that “she lacked the intent to deceive because, as a result of her deference to Mr. Balwani, she believed that various representations were true.”

There had been suggestions of a defense along these lines in the public court filings beforehand, but they contained virtually no details. At the time, I asked Carreyrou what he thought of the possibility that Holmes was somehow under the sway of Balwani, and he dismissed it as “absolutely laughable.” Balwani, he said, “was a terrible influence in general,” but “they were very much running the company together.” “They were constantly in touch, but at the same time, he deferred to her when there was disagreement. She was the ultimate decider.” After the newly released filings became public, a forensic psychiatrist interviewed by the Journal expressed skepticism about the defense, telling the paper that PTSD can impair behavior for short and discrete periods but that it would be harder to explain alleged misconduct “over the span of a great deal of years.”

It remains to be seen whether Holmes will go through with this defense, and it will presumably depend on whether her lawyers think they have done enough to undermine prosecutors’ argument by the time the government rests its case months from now. The persuasiveness of the defense would rely heavily on the credibility of Holmes’s testimony, and whether her lawyers can present any contemporaneous corroboration of her claims. (Balwani has vigorously denied the allegations, calling them “deeply offensive” and “devastating personally.”) It would also present the government with a difficult strategic decision given the sensitivity of the allegations — whether to suggest that Holmes is fabricating the claims of abuse in a last-ditch effort to evade responsibility, or whether to take the position that she may be telling the truth about Balwani but that she is still responsible for her role in their alleged scheme.

Suffice to say that there is a considerable risk that the jury will not find this persuasive — and that it could even backfire if they conclude, in the worst-case scenario, that it is more evidence that Holmes is a serial and unrepentant liar. That said, her odds of convincing everyone on the jury may seem low, but she would only need to convince one person to hang the jury, which would be tantamount to a victory.

If that were to happen, it would not do much to resolve the broader, prevailing cynicism about the performance of the country’s elite sectors in this age of political and informational uncertainty — a lack of confidence for which the Theranos saga seems to provide new and potent evidence. It would, however, be Holmes’s most remarkable accomplishment yet.