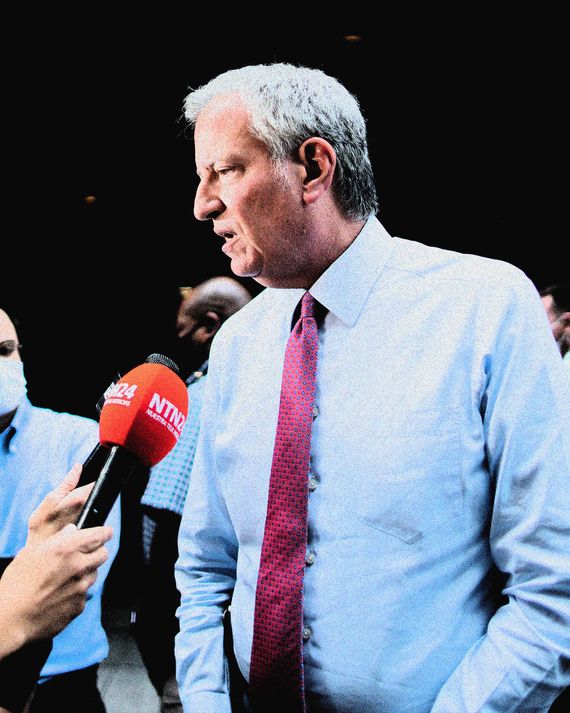

With fewer than 80 days left in his term, Bill de Blasio still has a chance to bring about extraordinary, lasting change in our city — but only if he gives up on the idea of running for another office.

The mayor, despite what the naysayers might tell you, is a talented and ferociously competitive politician. He has held elected office continuously for 20 years, winning three consecutive citywide elections against formidable opponents in the shark tank of New York politics.

He has a better chance of becoming governor than you might think. More on that below.

But first, consider what an unshackled de Blasio could do. A mayor who knew — and publicly announced — that he had run his final race could bring a level of political fearlessness to an already powerful position. With no need to curry favor with particular voting blocs, de Blasio would be able to do things politicians rarely even attempt: taking on entrenched interests, speaking inconvenient truths, rebuffing donors, and walking away from alliances that have outlived their usefulness.

Earlier this year, it looked like de Blasio might embrace the opportunity. He had been loosening up at his sometimes tense briefings, showing up at events like the Met Gala and generally having fun during what his aides dubbed the “Summer of Bill.”

In addition to having fun, the mayor took advantage of his lame-duck status to push forward with controversial policies that have drawn harsh criticism and lawsuits.

He ordered the city’s kids back into the classroom, specifically refusing to continue to offer the option of remote learning. Around the same time, he required that teachers and other school personnel be vaccinated or risk termination and quickly expanded the mandate to include health workers and anybody wishing to dine indoors.

De Blasio, a dedicated friend of organized labor, openly battled the correction-officers union over mass absenteeism and deteriorating conditions on Rikers Island, going so far as to sue the union (the lawsuit was later dropped).

And after years of delay, he has pushed for a rezoning that would add lower-income housing to wealthy neighborhoods like Soho and Gowanus.

Tough decisions from a soon-to-be-ex-mayor. So far, so good.

But the unexpected implosion and resignation of Governor Andrew Cuomo, de Blasio’s longtime nemesis, changed everything. Cuomo’s sudden departure left a power vacuum in the state capital that de Blasio believes he can fill. All of a sudden, Bold Bill has been replaced by Cautious, Calculating Bill, as de Blasio goes back to what he knows best: courting supporters and building the specific alliances needed to win the next election.

“I’ve talked to a number of people to say I want to continue in public service. There’s a lot to do,” the mayor told reporters in early October, responding to stories in the New York Times and elsewhere about his all-but-announced decision to run for governor. “I’m very proud of what this city government has done to fight COVID and move us forward. I got a lot to offer. I want to do more in public service. How that’s going to play out there’s time to figure out. But that’s my goal.”

A moment of clarity arrived at 4:59 p.m. on September 17, the close of business on a Friday evening, the day after Yom Kippur. That’s when the administration chose to release the final Mayor’s Management Report of de Blasio’s term — a time guaranteed to draw the least possible news coverage and commentary.

The MMR, a statistical compendium of more than 2,000 measurements of how city services are being delivered, is required under the City Charter. In the past, various mayors — including de Blasio himself — have held long press conferences to chew through the numbers and talk about the ups and downs of city management.

But de Blasio chose to bury the final report card of his administration — exactly what a guy thinking about his next campaign would do.

Not all the news in the MMR was bad. De Blasio’s eight years in office include outstanding achievements like the creation of universal pre-kindergarten and a higher graduation rate. But there have been some notable lapses, too.

Stabbings and slashings at city jails have skyrocketed by more than 100 percent over the last year, from 123 to 246. The Department of Sanitation reports that the number of streets it rates as “filthy” increased by 500 percent over the past year, even as the number of tickets issued for dirty sidewalks fell by 25 percent.

The mayor, who began his first term with an ambitious plan to end pedestrian deaths, has in reality seen a sharp increase. Some of his attempts to improve mass transportation have foundered: De Blasio created more bus lanes, but the mass-transit advocacy website Streetsblog notes that “buses have actually gotten slower in the de Blasio era, dropping from an average speed of 9.8 miles per hour in January 2015 to 9.2 miles per hour in August 2021. Local buses have similarly not budged, from 7.7 miles per hour in January 2015 to 7.7 miles per hour in August 2021.”

De Blasio chose to downplay this mixed record. And his final opportunity for sweeping change was similarly muted: the long-delayed announcement that the city will aim to reduce racial segregation in the schools by radically overhauling the procedures and curriculum for Gifted and Talented programs was quietly announced — on a Friday. The announcement included the caveat that the administration will take public comments on the plan for a couple of months, meaning actual implementation (or cancellation) will fall to the next mayor.

As for the question of whether de Blasio has a decent shot at winning the race for governor, the answer is “yes.” Jostling around as an unlikely winner in the rear of the pack, before making a late surge to the front, has been de Blasio’s sweet spot in the past.

Back in 2009, when he ran for public advocate, polls taken two weeks before the Democratic primary showed de Blasio trailing 14 percentage points behind the better-known Mark Green, a fixture in New York politics since the 1980s who had twice been elected to the post. De Blasio finished two points ahead of Green, then won a blowout victory against him in a runoff later that month.

In 2013’s crowded Democratic primary for mayor, de Blasio was polling in a distant fourth place as late as July before beginning a steady climb that led him to the front of the pack as other candidates — notably Anthony Weiner — publicly imploded.

It’s not a foolproof strategy, of course, as de Blasio learned during his disastrous run for president in 2019, when he joined the race late and failed to get traction. Polls showed 76 percent of New Yorkers didn’t want him to run.

But the latest Marist College poll shows incumbent governor Kathy Hochul with 36 percent support in a hypothetical matchup against Attorney General Tish James (24 percent), Andrew Cuomo (19 percent!) and Public Advocate Jumaane Williams (9 percent). Two other suburban candidates not included in the poll are considering entering the race: Suffolk County executive Steve Bellone and Congressman Tom Suozzi.

If the field for governor begins to look like the 2013 race for mayor — including the possible presence of a scandal-scarred candidate trying to make a comeback, with Cuomo playing the role of Weiner — de Blasio could see the kind of race he has already proved he can win.

A run for governor might be good for de Blasio, but it would likely doom any hope of seeing the mayor take political chances or make ambitious and controversial moves in his final months.

One bold move worth taking would be to fight fearlessly for a replacement of Gifted and Talented accelerated learning and other proposals first given to him by his own School Diversity Advisory Group in 2019. The task force called for, among other things, an immediate, focused effort to move 50,000 students — less than 5 percent of overall enrollment — into more racially integrated schools. The task force also recommended creating a position of “chief integration officer” that would report directly to the chancellor.

Another big step de Blasio could take would be to push the City Council to pass a law banning co-op boards from rejecting applicants without providing a reason for the denial — an exemption from fair housing laws that allows boards to engage in racial discrimination without consequence. A bill to close that loophole has been kicking around the council since de Blasio was a member.

And he could drop the city’s long-standing legal opposition to a lawsuit challenging the city’s community-preference rules, in which access to scarce, newly built city-subsidized apartments are determined by a lottery — one that deliberately gives an overwhelming mathematical advantage to people who already live in the area where a new subsidized development is built. Giving first crack at new apartments to the same people already in the area entrenches the racial segregation of our neighborhoods, according to the civil-rights organization that sued the city years ago. De Blasio should have settled the lawsuit long ago.

The city’s property-tax system is an unholy, unfair mess that allows the owners of multimillion-dollar mansions in gentrifying areas to be taxed at a much lower rate than modest middle-class homeowners pay. De Blasio vowed to tackle the thorny issue this year but never got around to it — and now, perhaps, never will.

A timely, aggressive, all-out campaign to rezone more of New York and desegregate our schools and neighborhoods would change our city. Instead, we have a mayor, eager to hit the campaign trail, who wants to change the subject.