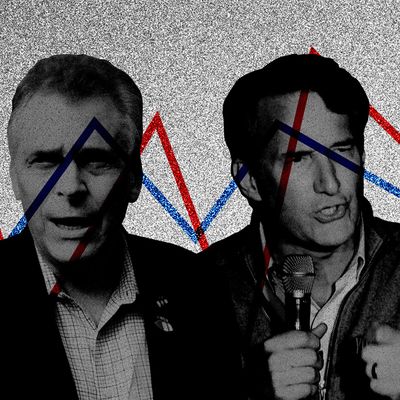

Less than a week before Virginians pick their next governor, there is a sense of frenzied uncertainty hanging over the race. That much isn’t surprising — the polling between Democrat Terry McAuliffe and Republican Glenn Youngkin is extremely tight. What many anxious voters may not appreciate, though, is that, given the state of the polling industry, there’s a good argument to be made that the freak-out should actually be much worse.

Pollsters are nearly a year into battling the four-alarm fire set by their general-election disaster in 2020 — the biggest national-level polling miss in nearly half a century. One year ago, Democrats rolled into Election Day confident that they would see a relatively easy Joe Biden victory — remember the closing-stretch Quinnipiac poll showing him up five in Florida and the CNN-SSRS survey with a margin of six in North Carolina, or the Morning Consult poll with Biden up nine in Pennsylvania? And, of course, there was the USC projection of a 12-point national gap. Trump, of course, won Florida and North Carolina and came perilously close in the Keystone State, with the margin there figuring prominently in his postelection lies about a rigged vote. To simplify a bit: Across the country, pollsters seemed to systematically undercount GOP support, despite the fact that they were trying very hard, after some issues in 2016, not to do that.

But with the political world entirely focused on Virginia, looking to glean lessons about the state of the national parties, the fate of Biden’s agenda, and Americans’ hope for the future, the pollsters — the people who give us a sense of what to expect in elections — are offering a new round of projections without ever having quite figured out what went wrong last year. That means there’s no comfort to be found in the latest numbers — for hopeful Republicans, certainly, but especially for Democrats desperate to keep Richmond blue and get reassurance about Biden’s governing ambitions.

The industry set out to resolve all the ugly questions around the disaster of 2020 in the standard manner: with a big autopsy. In July, the American Association for Public Opinion Research released its eagerly awaited (in the biz) report with the cooperation of a range of political and academic researchers. It first concluded that that year’s national-level polling error — 4.5 percentage points, on average — was the highest it could find in four decades, and that the state-level surveys were as far off — 5.1 points — as they had been since the group started tracking that data in 2000. (So, yes, it really was as bad as it seemed on Election Night.) And 2020’s mistakes were different from 2016’s, it continued: Then, pollsters had undervalued education levels in weighing their research, which led to underestimating Trump’s support. Now, though, something bigger and scarier had happened. They just still couldn’t conclude what, exactly, that was.

That discomfiting research wasn’t the only effort of its kind. Sensing doom if they didn’t address what was clearly a fundamental problem for pollsters, five rival Democratic Party polling firms — including Joe Biden’s — secretly joined forces two weeks after the election to find a diagnosis and solution. But when they revealed the collaboration in April, they still had no solid answers. One pollster involved in the Democratic effort told me the coalition was still deep in its experiments and didn’t expect to know much at all for at least a few more months, “at a minimum.”

This is all, clearly, a major issue. It’s not just that Americans — particularly dialed-in partisans, volunteers, and prospective donors — don’t know what to expect from their elections in the short run. It’s also building into a larger-scale and longer-term mistrust of polling, too. This, in turn, is hampering politicians’ confidence in the strategic decisions they’d usually make based on their numbers.

It’s also just annoying: Who wants the “you can’t trust the polls!” guy at the party to actually be right?

None of the easy fixes have cut it so far. The AAPOR report preempted one obvious question: No kind of interview — phone, text, online — clearly outperformed the others in terms of accuracy in 2020. It also ruled out the notions that 2020’s issues were caused by anything from late-deciding voters who skewed the numbers to mis-weighted demographics when pollsters tried projecting the makeup of the electorate. It couldn’t even be poll respondents’ hesitance to admit they liked Trump. The Democratic groups, for their part, said they’d fixed their (relatively small) 2016 error by increasing representation for white non-college voters in their samples, and that their polling results in 2017 and 2018 races looked good — at least before 2020 spoiled that fix and revealed that their numbers were especially bad in more Republican areas of the country.

So what’s a pollster to do? In talking to a range of nonpartisan and party-affiliated pollsters in recent weeks, I found that many dismissed, but laughed nervously about, the least scientifically sound idea of all, which unfortunately would have looked on the surface like a fix in 2020: just artificially slapping four extra points of support on Trump’s side.

When Patrick Murray, who runs the Monmouth University poll, explored his data earlier this year, he told me, he explored whether there was “any way I could have modeled my electorate on anything other than arbitrary guesses that would have gotten me closer to the endpoint. And the answer was basically no. If I had the ability to jump ahead in time and know exactly which voters that spoke to me were going to show up to vote, we still would have been off with the Trump vote share.”

Add it all up, and the liberal nerves in Virginia are not just understandable but warranted: One week before polls close, McAuliffe’s polling lead over Youngkin is down to less than one point in the FiveThirtyEight average. If you take the tongue-in-cheek advice and give the Republican four extra points, Youngkin wins.

Here’s the complicated part: Plenty of pollsters do think they know what happened; they just don’t know how to talk about it, let alone how to fix it.

The likely problem, in short, is that they simply aren’t reaching a significant number of voters activated by Trump, perhaps because they don’t know how to find them, or maybe because those voters mistrust and therefore ignore polls. And if you aren’t in any kind of contact with a voter, it’s essentially impossible to figure out what’s motivating him or her, or what distinguishes them from the people who are answering you.

“We would argue nonresponse is, by far, above and beyond, the biggest issue here,” Johannes Fischer, the survey methodology lead for progressive polling outfit Data for Progress, told me this month. If nonresponse has always been a problem, its sheer scale is what’s new now.

Fischer’s group has spent the last few months testing new ways to reach Americans who haven’t been answering its questions, like physical mail, and trying to gauge whether there’s an optimal mix between texts, calls, online surveys, and mail to weed out biases. But mostly, the group has been digging into its data to see if it can find a way to learn more about these kinds of voters. “There’s all sorts of things we can ask people in a survey that can correlate with their vote choice, and that will provide additional predictive value,” explained Colin McAuliffe, one of Data for Progress’s co-founders. In other words, it’s trying to find new ways to learn about respondents’ motivations for its future polls. For example, the way individuals answer questions about climate and racial resentment has been especially effective at predicting the difference between a Biden 2020 voter who now disapproves of him, say, and a Trump 2020 voter who now approves, said McAuliffe.

It’s a nuanced endeavor that’s circumscribed, by definition, by the fact that pollsters still don’t have their own information on the people who simply don’t respond. For that, they’re studying updated voter files whenever they’re released, and trying to match the results with their own findings. The idea is to be able to model a fuller view of the overall electorate based on more than basic partisanship and demographics — to go beyond just searching for certain kinds of Republicans with certain kinds of backgrounds in certain geographies.

Still, a more fundamental disagreement has bloomed in the scorched earth that 2020 left behind.

Some pollsters, such as Murray, have argued that the nonresponse problem appears to be Trump-specific, since the errors were far more pronounced in 2016 and 2020 than in any of the intervening or proceeding years, including the 2018 midterms. “The evidence suggests that when Trump’s name is not on the ballot itself, we don’t have a problem with missing a portion of the electorate that doesn’t want to talk to us,” he said. “The question is: Do we treat the 2020 election as something entirely brand-new, so we have to add a four-point arbitrary margin on the model for Republicans? Or do we look at when Trump has not been on the ballot and our polling has basically been okay? My working hypothesis is that’s probably the better path to take, which means our 2021 polling isn’t that different than what it was in 2017.”

Others still think that’s too rosy. “If it’s true that one person can have this wild effect on polls, then why can we not detect that in real time?” asked McAuliffe. McAuliffe didn’t raise the obvious next question: And what happens if Trump runs again?

Either way, there’s clearly still an issue to be fixed, as this year’s first big race demonstrated: Polling showed a neck-and-neck contest over the summer in California’s gubernatorial recall election, only for it to widen dramatically to 16 points in FiveThirtyEight’s final average. But Gavin Newsom, the incumbent, ended up with a 24-point win. It was another dramatic polling miss, though perhaps one that could give Democrats some hope that without Trump on the ticket, the specific kind of polling skew that worries them so much — hidden Republican support — could be far less of a problem. If that’s true, it would suggest Terry McAuliffe is still on track to breathe a sigh of relief in Virginia, and that Democratic governor Phil Murphy can also exhale in New Jersey, where polls have had him winning his own reelection easily for months, but only recently narrowed to a single-digits margin.

Still, even if all this proves true, the potential for Trump’s return is an inescapable concern, especially since pollsters’ other big worry these days is plummeting trust in their product. Some firms’ short-term answer to the trust deficit has been to crank up their transparency and emphasize that their polls aren’t predictions. Murray’s Monmouth has started releasing multiple sets of possible outcomes based on different turnout models in both the upcoming Virginia and New Jersey governors’ races.

But this is the optimistic solution. A more drastic alternative does exist.

After Barack Obama’s reelection in 2012, Gallup announced it was getting out of the election game altogether. The horse-race surveys just weren’t worth all the political and reputational shit flying the company’s way, especially since there was no reason to believe issue polling was facing the same problems as candidate head-to-heads. (This remains true, as Murray pointed out: Asking people whether they’ve gotten a COVID-19 shot tends to produce results that match up with government vaccination data, for instance.) This summer, Politico reported that The Wall Street Journal and NBC were giving up on their three-decade-old polling collaboration, too.

Multiple pollsters that I talked to said they were loath to throw their hands up entirely. But, a few admitted, a whispered question has been getting a little louder in their professional circles in recent months: Is it still worth it?

That question may get a clearer answer on Tuesday.