In the ongoing debate over what Congress should do with Joe Biden’s agenda and the bipartisan infrastructure bill, there’s an assumption that has often gone unexamined: that what Democrats do or don’t accomplish this year will have a major bearing on the 2022 midterms, and in turn on their continued ability to govern for another two years. That presumption is actually shared by two diametrically opposed schools of thought. Most progressives hope an ambitious version of the Build Back Better legislation will energize otherwise checked-out Democratic constituencies and get them to the polls in 2022. Some centrists and nonpartisan observers believe a minimal set of legislative goals and accomplishments will satisfy an electorate that mostly just wanted to get rid of Donald Trump in 2020, without upsetting swing voters concerned about “overreach,” big spending, or inflation.

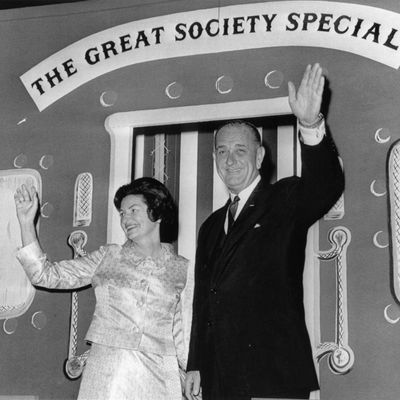

As Ron Brownstein points out, there is a lot of counter-evidence available to rebut the idea that big, bold legislative agendas tend to produce big electoral awards in midterms. Going all the way back to 1913-14, a Democratic Congress following Woodrow Wilson’s leadership enacted a federal income tax and created the Federal Reserve Board and the Federal Trade Commission. Democrats lost 61 House seats in 1914. In 1966, after Lyndon Johnson lashed his Great Society legislation (along with crucial civil- and voting-rights laws) through a Democratic Congress, his party lost 47 net House seats, four Senate seats, and eight governorships. The conservative legislative revolution begun by Ronald Reagan in 1980 also produced a midterm backlash in 1982. The enactment of Obamacare in 2010 led to one of the worst midterm rebuffs of any newly elected president, with Democrats losing 63 House seats, six Senate seats, and six governorships.

But there’s also not a lot of evidence for the idea that minimal agendas or accomplishments wear better on a midterm electorate. The systemically moderate Dwight D. Eisenhower lost ground in both the 1954 and 1958 midterms. The most conservative Democratic president of recent years, Jimmy Carter, had limited legislative success and his party didn’t do well in 1978. Mr. “Different Kind of Democrat” himself, Bill Clinton, had to abandon his boldest legislative item, a health-care reform bill, before the 1994 midterms and Democrats lost 52 House seats, eight Senate seats, and ten governorships.

The historical record suggests that barring some big realignment, the party of a newly elected president will lose some power in the ensuing midterms no matter what it does or does not do. The only exception since the 1930s was in 2002, when a post–September 11 electorate rewarded an extremely popular George W. Bush with modest gains that probably had little to do with with legislation or domestic politics generally. Given the small margins of control Democrats have in Congress right now, the odds for extending their trifecta are very low, and there is no obvious strategy for changing those odds unless Joe Biden overcomes partisan polarization to become very popular.

So what is the upshot for Democrats struggling with the electoral implications of the deal still under construction? Chill.

History aside, it does not appear that a lot of voters are tuned into the negotiations in Washington, complex as they are, involving a host of initiatives being enacted under budget procedures that maybe 100 people in the country really understand. Policies are almost invariably overrated as “voting issues”: Even when they seem to be front-and-center, as with Obamacare in 2010, it’s usually some meta-message surrounding them that’s really moving votes (e.g., “government takeover of health care,” which Democrats are going to be accused of no matter what).

So the smart thing for Democrats to do is to enact policies that they and their constituents strongly support, which will improve conditions of life in the country (maybe not right away, but eventually). That will give them a legacy they can defend when Republicans come to tear it down, or better yet, decide to leave it alone because it’s popular. If Democrats are not consumed with midterm politics they cannot entirely control, moreover, they can give themselves more time to get it right: maybe in a subsequent budget reconciliation bill next year.

A lot of the frantic behavior surrounding the current Build Back Better and infrastructure negotiations is generated by self-imposed deadlines arising from electoral concerns. One reason for Nancy Pelosi’s October 31 deadline for a House vote on the bipartisan infrastructure bill is to help Terry McAuliffe with the Virginia governor’s race on November 2. It’s not at all clear it’s going to matter. It’a often assumed 2022 will be a legislative graveyard because of the midterms at the end of the year. That’s only true if Democrats treat it that way. The only real deadline for enacting legislation is in January 2023, if Democrats do lose control of one or both chambers of Congress in the midterms. If they are smart and very lucky, they may have another two-year window and another one after that. The sky is not falling. And the next election is going to follow patterns far more complicated and far less subject to manipulation than you’d think from the talk of this or that program or bill being all-important.