Overstretched supply chains have been the bane of the Biden economy. This year, the United States has enjoyed one of the fastest post-recession job recoveries in history, a long-awaited spike in business investment, rising wages, falling child poverty, and record household wealth. But shortages have caused rising prices, which have eroded the real value of Americans’ paychecks. Together, inflation and the supply-chain crisis have darkened consumers’ perception of the recovery. One gauge of consumer sentiment found that Americans were more pessimistic about their nation’s economy at the start of this month than they’d been at any time since the COVID-19 pandemic began.

Today’s inflation has myriad causes. But the fundamental problem is that the 2020 crisis — and the fiscal policies pursued in its wake — had three massive, contradictory consequences for the global economy: (1) As consumers spent more of their time sheltering at home, they started devoting a greater share of their incomes to purchasing goods relative to services; (2) robust stimulus programs left consumers with more disposable income to spend; and (3) pandemic lockdowns and their ripple effects snarled the global supply chains that facilitate the creation and disbursement of consumer goods.

Put these together, and you get a giant mismatch in supply and demand — and with it, clogged ports, scarce semiconductors, energy rationing, and rising consumer prices.

One way to resolve this mismatch would be to reduce demand, which is to say, to pursue policies that lower the amount of money that Americans have to spend on stuff (e.g., raise interest rates to increase the cost of credit, cut social spending to reduce households’ disposal incomes, etc.). That route would ease inflation at the cost of slower economic growth and higher poverty.

Alternatively, policymakers could let the economy run “hot” for a bit and hope that supply eventually rises to meet demand, as major manufacturing centers return to full capacity and firms expand production to keep up with consumer appetites. This approach comes with a higher risk of inflation, but also better prospects for growth and employment.

Over the past week, the case for the latter option has grown stronger. The global supply-chain crisis is far from over. But there are signs that the worst of it is now behind us. Recent reports from Bloomberg and The Wall Street Journal spotlight six encouraging developments:

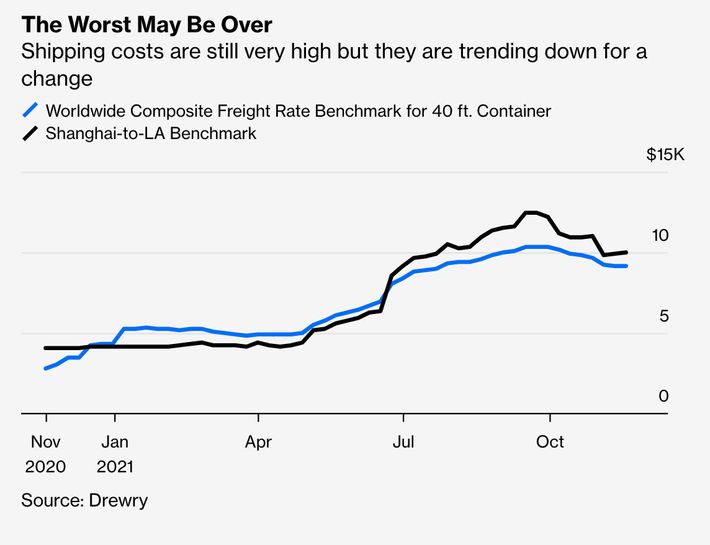

1) Shipping freight rates are falling.

If you want to secure yourself a 40-foot shipping container today, it’ll cost you about 20 percent less than it would have earlier this month. The average global freight rate has fallen for eight consecutive weeks.

And there’s reason to hope that this (slow but steady) decline will persist even as Christmas draws near, since:

2) Major U.S. retailers have already stockpiled the goods they expect to sell over the holiday season.

The potential for the holiday season to turbocharge the global supply-demand mismatch, as households across the Christian world simultaneously increase their goods spending, has long worried analysts. But America’s big-box stores saw this crunch coming from nautical miles away, and they’ve been steadily building up inventory in anticipation. Last week, Walmart, Home Depot, and Target all told investors that they’re fully stocked for the holidays. And the firms’ balance sheets lend credence to those claims. Despite robust retail demand, Target is sitting on $2 billion more in inventory now than it held at this time last year, thanks to the company’s pre-Christmas preparations.

3) Backlogs at major ports are down a bit from record highs.

The ports are still a mess. Last Friday, there were 71 container ships anchored offshore outside the ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. That figure is approximately 71 ships higher than the typical number of vessels forced to anchor offshore before the pandemic.

If the lines at ports remain historically long, though, they are starting to move at a brisker pace: The number of container ships that have lingered at the Port of L.A. for longer than nine days has dropped by about one-third since October, when the port started threatening to fine dawdling vessels.

Analysts expect the strain on ports to ease considerably by February: Once the December holidays have passed (and China’s manufacturing sector takes a week off for Chinese New Year), demand for shipping containers should fall considerably, even as investments in expanded freight capacity start to come on line.

4) Chinese manufacturing is powering up.

In China, the government has long capped the prices that utilities can charge consumers for electricity. This year, as the global recovery elevated energy prices, that regulation pushed many Chinese utilities to the brink of insolvency. With the cost of coal skyrocketing, and consumer price caps fixed, power plants were forced to choose between operating at a loss or shutting down. As a result, utilities started rationing electricity between households and the manufacturing sector, forcing Chinese firms to scale back production. This exacerbated the global shortfall in the supply of goods.

But in recent weeks, as the government has empowered coal-fired plants to charge higher prices, the electricity crunch has eased and manufacturing has returned to something resembling normal capacity.

5) COVID-related factory closures have let up in Southeast Asia.

Earlier this year, COVID-19 outbreaks in Malaysia and Vietnam forced authorities to limit production. That took a toll on the global supply of textiles and semiconductors. But output at factories in Southeast Asia rebounded over the past month, as case counts fell and normal production resumed.

6) Car production is revving up.

In October, U.S. manufacturing output reached its highest level since March 2019, a surge driven by an 11 percent jump in the production of automotives and car parts. Meanwhile, Toyota has set a December output target that exceeds the Japanese firm’s pre-pandemic norm. These developments suggest both (1) the global supply of motor vehicles is in the process of catching up to demand, and (2) the global shortage of semiconductors is easing somewhat, since chip shortfalls had previously been restraining automotive manufacturing.

All this said, it isn’t hard to see how the global supply chain’s fledgling recovery could be undone. Existing progress is highly limited; the global benchmark shipping rate is still 200 percent higher than it was this time last year, indicating there’s still a supply crunch in shipping capacity. Labor shortages are still hindering production the world over. While developed countries struggle to muster an adequate army of truck drivers, developing ones are still waiting for rural migrant workers who fled urban centers at the pandemic’s onset to return from their ancestral villages.

What’s more, the wealthy world’s mindless refusal to finance a rapid global-vaccination campaign has left key production nodes especially vulnerable to new outbreaks; only about a quarter of Vietnam’s population is fully vaccinated, and cases there have risen sharply in recent weeks. Meanwhile, even in the West, vaccine hesitancy combined with winter’s return is breathing new life into the pandemic. Germany, a major global exporter, is mulling another lockdown as COVID tests its hospitals’ capacity once again.

In the short term, COVID’s resurgence could ease commodity crunches in some sectors. Locked-down economies use less energy than open ones, and thus, as case counts have climbed in Europe, oil prices have fallen.

Ultimately, though, supply chains cannot fully recover until vaccines and antivirals render COVID a rarer and less serious ailment than it remains today. The best macroeconomic policy may therefore be a sound, global public-health policy. Vaccinating the world will do more to ease price pressures than raising interest rates or slashing spending.