Last month, Facebook and Instagram removed one of Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro’s trademark “live” broadcasts from their servers because he suggested there was a link between taking a COVID-19 vaccine and getting AIDS. It was the first time that Mark Zuckerberg’s companies took the extreme-right politician off the web for violations, but it may not even have been his most outrageous entry into anti-vaxx discourse. Last year, he famously remarked that “if you take the vaccine and turn into an alligator, that is your problem,” after saying he would not get the shot himself and pointing out that Pfizer would not take responsibility for any unknown side effects. In September, Bolsonaro shook U.K. prime minister Boris Johnson’s hand, then shocked everyone in the room by saying he had “not yet” been vaccinated.

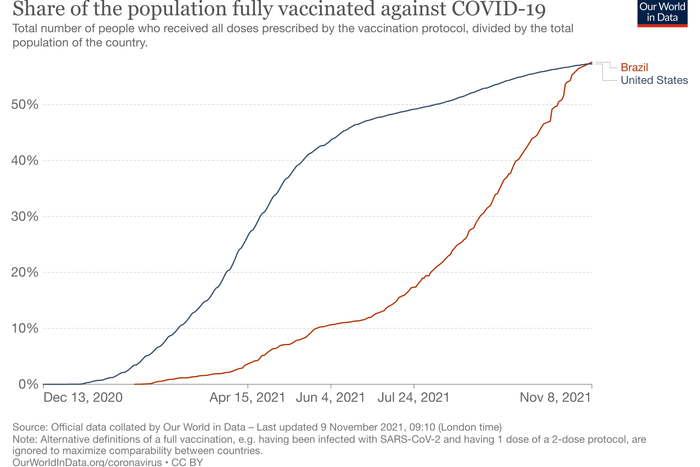

The vast majority of Brazilians, however, are taking the shots as soon as they can get them. Here in São Paulo, the most populous state, the government is reporting that 100 percent of adult residents have received at least one dose. This is likely a little higher than the real figure, owing to population growth since the last Census and “vaccine tourists” who came to the country’s richest state to get their shot, but national surveys point to a vanishingly small anti-vaccine population. In July, only 5 percent of respondents told the pollster Datafolha they did not plan to get the vaccine, and the number may have gone down since then. In a September Ipsos poll, Brazilians showed the strongest support for booster shots among all the countries surveyed. Despite the fact that vaccines have arrived in Brazil much more slowly than they did in the U.S., far more Brazilians have received a shot than Americans have.

That means that a whole lot of Bolsonaristas are choosing to get vaccinated, no matter what their president says. Two things explain this apparent contradiction, experts say. First, Brazilians have deep trust in their public-health system, and especially its vaccination programs, which was built up over several decades. And second, Bolsonaro is unable, or unwilling, to modify his political tactics in the face of failure.

“Bolsonaro supporters are getting vaccinated, even if they might speak out against some aspect of the programs. Brazilians have a long tradition of getting vaccinated, for free, and the vaccinations are seen as a right, not a duty,” explains Natalia Pasternak, a microbiologist and president of Instituto Questão da Ciência. “This goes back to the end of Brazil’s dictatorship, a very audacious public-health-care system, and some very good immunization campaigns.”

In 1988, Brazil’s new Constitution gave rise to the Sistema Único de Saúde, or SUS, a single-payer universal health-care system modeled on Britain’s NHS. Now almost every Brazilian knows where they can see a doctor for free, even if rich people pay for private health care. The public system is supported by 78 percent of the population. When people complain about SUS — even people on the far right — they usually ask for more investment into it, and better free services, rather than dismantling. And Brazilians of all ages remember Zé Gotinha, an iconic cartoon that has promoted vaccination programs over the years. Perhaps best translated as “Johnny Droplet,” he was created (by the government) to assure people that vaccinations are safe, or even fun. When it came time to get a COVID-19 vaccine, most people knew exactly where to go.

“Dealing with SUS just makes everything easy,” says Renato, a small-business owner on the São Paulo coast who voted for Bolsonaro but got two vaccinations as quickly as he could. He says he goes every year to get his free checkup in the public system, even though he could afford private care. Not far from his home, Bolsonaro mounted a new anti-vaxx stunt recently. On a long holiday weekend, the president showed up to attend a game at Santos Football Club — where both Pelé and Neymar became famous — only to be barred at the entrance since he hadn’t been vaccinated. It made a splash in the media, which often seems to be the point of Bolsonaro’s antics.

Renato is close to the ideal type of Bolsonarista — male, comfortably middle class, white, educated but outside the often-progressive urban cultural elite — and his social circle consists of a lot of other Bolsonaro voters. For this reason, he asked that his last name not be used in this article. “I just think Bolsonaro is wrong about this one, and a lot of people know it. A lot of my friends that were saying over the last year on Facebook and everywhere else that they weren’t going to get vaccinated. And now they are all vaccinated.”

In September, Bolsonaro’s approval rating hit its lowest point since he took office in January 2019 with 53 percent now disapproving of the president. Both his disastrous handling of the pandemic and his repeated threats to carry out a coup d’état have proved unpopular with voters. But 24 percent ranked his performance as “average” and 22 percent said he is doing a good or great job.

An obvious explanation for Bolsonaro’s defiant anti-vaxx posture is that he is playing to his (shrinking) base. But there is also an international element to consider, says Gerson Salvador, an infectologist and public-health expert at the University of São Paulo hospital. “He is not just speaking to Brazilians; he is speaking to the global right. His discourse is very similar to that put forward by the Trump movement, and he has always seemed to be influenced by Steve Bannon. He is interested in maintaining some relevance among global right-wing and anti-democratic forces.” It seems that anti-vaxx sentiment is one North American import that has not taken off among the Brazilian population, but that does not mean Bolsonaro’s posture had no consequences. Last year, Bolsonaro repeatedly declined to acquire doses of vaccine despite repeated offers from Pfizer. One researcher calculated that decision alone could have led to 100,000 unnecessary deaths.

So far, just over 75 percent of Brazilians have received at least one shot of a COVID vaccine, compared to 66.6 percent of people in the U.S. The percentage of Brazil’s population that is fully vaccinated — 57.6 percent — is also now higher than in America. Both numbers continue to rise steadily as less populated and poorer Brazilian states are still catching up with the economic powerhouses of Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. In 2021, most of the world’s COVID-vaccine doses went to rich countries, especially the U.S. In Brazil, vaccinations began in January, but there were very few doses available in the country, partially because of Bolsonaro’s decisions. There are many people still eagerly awaiting the chance to get their first or second shot, very much unlike in the U.S., where vaccines have been fully available to most people for several months.

Brazil’s position in global health debates has changed under the extreme-right president. Two decades ago, Brazil led a successful charge to break patents on HIV/AIDS treatments, as countries in the global South argued their public-health concerns took precedence over the profits of pharmaceutical companies. But last year, Brazil lined up with rich countries to oppose waiving patents for COVID-19 vaccines, once again putting Bolsonaro in lockstep with the U.S. and Donald Trump.

Domestically, Bolsonaro’s constant flirtation with the global anti-vaxx movement may not be doing him any good. But that does not mean it is not fitting with his political orientation, says Flávia Biroli, a political scientist at the University of Brasília. During his entire political career, he has taken violently provocative positions and fundamentally rejected democracy — including the idea that the state owes any kind of responsibility to its citizens. He has been constant on these points for decades, beginning with the TV appearance in the 1990s where he called for the murder of tens of thousands of Brazilians. “On the question of vaccines, it seems to be that he’s doubling down on an error, and he has not been able to get out of the corner that he painted himself into,” says Biroli. “But that is simply who he is. For a few years, he found himself in a country where his long-established antagonistic and irresponsible posture worked to deliver him political victories. It was unlikely that he could build an entirely new political project, and become a man that adapts to popular opinion, just because the situation in the country changed.”

Coronavirus deaths have been declining steadily in Brazil for months. An average of less than 240 people have lost their lives to COVID here over the past seven days, compared with more than 1,100 in the United States.

This post has been updated.