New Yorkers appeared caught off guard by the Omicron variant ripping through the city this week, but medical centers say they are better equipped to handle what may come than they were at the beginning of the pandemic.

The state and the city reported record-breaking case counts two days in a row thanks to Omicron, and this is likely to be only the beginning of the onslaught. How much that translates into severe illness that hospitalizes people or worse is an open question. Hospital leaders predict they will treat an increase of patients carrying the highly contagious variant this winter but said there is enough room in their facilities to care for severe cases and avoid the need for drastic measures. If anything, their concern is a shortage of health-care workers.

On Wednesday, the heads of Mount Sinai, New York-Presbyterian, Montefiore Medical Center, and Northwell Health discussed strategies for handling the variant on a conference call convened by Greater New York Hospital Association president Ken Raske. No one indicated they were worried they would run out of beds or protective equipment as happened during the first COVID wave, according to Northwell Health CEO Michael Dowling.

“We do anticipate the number will increase after Christmas because people will get together for Christmas celebrations and may not take precautions, but we don’t have a capacity problem at all,” Dowling, who heads the state’s largest hospital network, told Intelligencer. His prediction is based on data from South Africa’s most populous province showing Omicron cases there have been milder compared to other waves in the country. Experts have cautioned against extrapolating one country’s experience to another, and hospitalizations lag new cases. “The fact that people are getting positive out there, if they feel discomfort and they’re not in the hospital, they can deal with it,” he said.

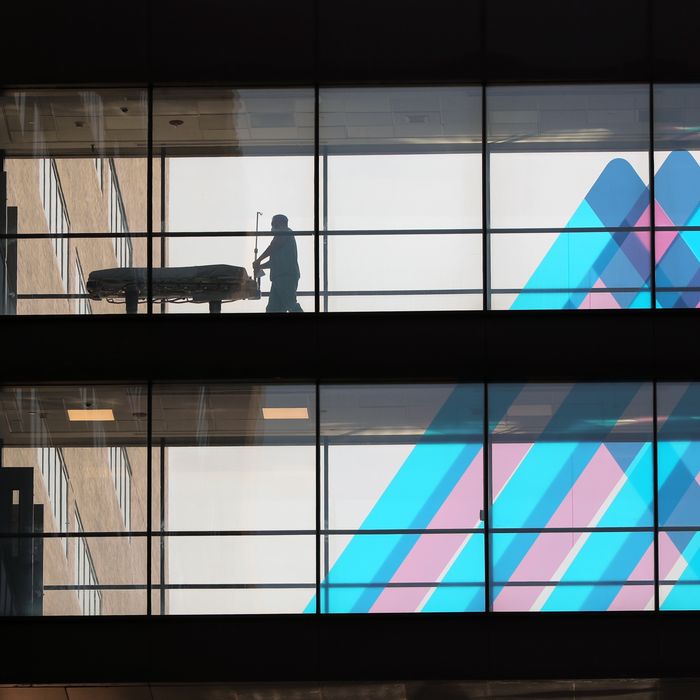

The city’s public hospitals, which treated 4,000 patients largely from disadvantaged communities in the spring of 2020, have less flexibility to add beds and health-care workers than private ones. Private hospital leaders insist there will be better coordination to ensure no one location fills up with COVID patients. The city’s current rate of hospitalizations for COVID patients is low, although people with COVID-like illnesses in hospitals nearly doubled from 116 patients on December 3 to 214 patients by December 16, city health data shows. At Northwell Health, there were 386 COVID patients on Friday across its 22 hospitals and ambulatory care centers, compared to 3,500 in April 2020.

The current portrait statewide is less sanguine. “We are in the midst of a Delta surge,” State Health Commissioner Mary Bassett said Thursday in a press conference. “We have Omicron in the wings. It’s been identified here in New York State. And we also can’t forget that with winter comes seasonal influenza.”

Delta has already pushed hospitalizations in the state up 70 percent since Thanksgiving, Governor Kathy Hochul said on Thursday. Medical centers have been filling up for weeks in the regions of Western New York, Finger Lakes, and North Country. There has been a 10 percent decrease in hospital capacity upstate, prompting Hochul to call on hospitals above 90 percent full to cancel elective surgeries.

The state has about 50,000 hospital beds with another 15,000 beds that can be made available when elective surgeries are canceled. “Staying below the 15,000 number is crucial and as long as the rate of growth is slowed, it will give time to load balance between hospital systems,” Gareth Rhodes, a former member of the state’s COVID-19 task force, said in an interview. “At the current rate of growth in hospital numbers, it would take months to overwhelm the state’s hospital system and the battle now is getting through the holiday season until January when you will likely see the numbers start to go down.”

The more immediate concern for hospitals are staffing shortages. Nurses, lab technicians, and support staff have steadily left the industry during the pandemic. A small number of health-care workers left the workforce due to the state’s vaccine mandates, but most appear to be quitting due to burnout.

Nurses in particular are in demand. City hospitals are experiencing a 13 to 14 percent turnover rate (the usual rate is 4 to 5 percent) and competition from travel nursing agencies, which pay substantially higher wages, contributed to the labor shortage. New York-Presbyterian is recruiting about 250 nurses a month, Bloomberg News reported in November. And nurses at Mount Sinai demanded the hospital step up hiring and fill 100 open positions at an early December rally.

Even if hospitals have enough beds, the nurses who remain will have more patients to manage. “When we talked about bending the curve, one of the primary concerns we had was a fear the hospital system would be overwhelmed,” Bill Hammond, a senior fellow of health policy at the Empire Center, an upstate think tank, said. “People get sick and die all the time but the difference is if they get sick and die at a rate hospitals can’t keep up with it. That’s a scary situation.”

The speed of Omicron’s spread appeared to catch city and state leaders by surprise. Cases doubled in a week and then again in two days. The de Blasio administration scrambled Thursday to respond, announcing the city would distribute 1 million free KN95 masks and 500,000 rapid at-home COVID tests, extend hours at testing sites to seven days a week, and increase inspections ensuring businesses follow indoor mask requirements. “It is clear that the Omicron variant is here in New York City in full force,” Mayor Bill de Blasio said.

New Yorkers waiting for hours at COVID testing sites did not need a reminder. Long lines have snaked around the block at urgent-care clinics and NYC Health and Hospital locations across the city for several days, due to a doubling of demand, according to a top H+H official. The de Blasio administration also closed 20 city-run testing centers in November as federal funding for test and trace efforts was cut in half, The City found.

The Omicron wave is already shaping up to be the first challenge of mayor-elect Eric Adams’s new administration when it begins in less than two weeks, but his plans remain vague. Adams’s health transition committee had its first meeting Friday, according to members of the committee, where they discussed a response to Omicron. The day before, he announced Thursday he would build a COVID command center in downtown Brooklyn, but when a reporter asked about hospital staff shortages, Adams said he would convert the Javits Center to a field hospital again, which didn’t address the nursing crunch. Adams supported the state’s indoor mask requirements but has expressed concern about de Blasio’s pending vaccination mandate for private-sector workers, saying his own team would analyze the data before he makes a decision. Adams will likely keep NYC Health and Hospitals CEO Mitchell Katz, who has run the city’s COVID-testing program, a person familiar with Adams transition team told Intelligencer, but replace city health commissioner, Dr. Dave Chokshi. (Other reports have said Adams would keep Chokshi and Politico also reported Katz would likely stay on.)

Adams has resisted more aggressive measures at curbing COVID, saying, “It’s going to take a lot for me to lock down the city, it’s going to take a lot.”

The incoming mayor may be right that the political support doesn’t exist for citywide lockdown measures, even as New York University moved final exams online and several Broadway performances and restaurants announced closings due to COVID cases.

“The reality is there are social and economic concerns the mayor and governor are balancing as well,” Rachael Piltch-Loeb, an emergency preparedness fellow at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health, said. “That’s why tying this to a severity indicator, like something going on with the health care system, versus a case count or case positivity rate, could be a happy medium.”

More on omicron

- What to Know About the New COVID Booster Shots

- The Dismantling of Hong Kong

- What We Know About All the Omicron Subvariants, Including BA.2.12.1