The 21st century has made clear the inadequacies of various institutions that were once the bedrock of American society. In government, in business and in media, there has not just been a collapse in trust, but a sense that the systems we’ve got in place cannot cope with our present challenges.

The perfect microcosm of all this is the Baseball Hall of Fame.

A nearly century-old institution in bucolic upstate New York, the hall was founded on a durable, very American myth: Its location is the result of a fable that baseball was invented in rural Cooperstown by a teenage boy who later went off to become a minor Civil War hero. It quickly cemented itself into baseball lore at a time when the “national pastime” was truly the national pastime. Its first class of five inductees can still be recited with little effort by casual baseball fans, and the question of which players should be enshrined has been the inspiration for countless barroom arguments (and more recently Twitter fights).

Yet for a long time, the debates focused mostly on the merits of each candidate’s career. There were shocking snubs — Cubs great Ron Santo fell short year after year — and some bizarre inductions — the Veterans Committee somehow decided George “High Pockets” Kelly was worthy. But these fights largely focused on traditional measures of distinction like home runs and World Series victories, as cranky beat writers and new-school number crunchers bickered over what statistics best define baseball greatness.

But as with so many facets of American life, things have descended into murkier territory.

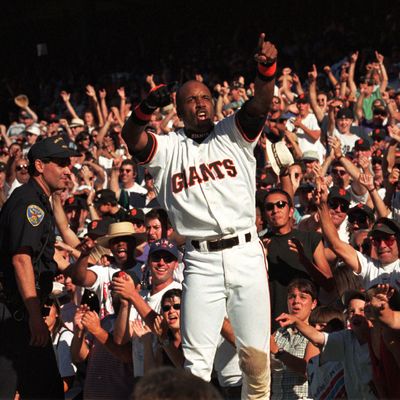

There is no question that, measured by talent alone, Barry Bonds is a Hall of Famer. By that metric, there’s also no question that Roger Clemens is a Hall of Famer. Ditto for Curt Schilling, Manny Ramirez, and Alex Rodriguez, for that matter. Yet none of them was elected on Tuesday.

In fact, Bonds, Clemens, and Schilling all officially fell off the ballot. After ten years of consideration, none of them had received the 75 percent vote required to be enshrined. Under Hall of Fame rules, veterans committees will consider their candidacies in future years, but that means getting in through the back door. Bonds has more home runs than anyone else in the history of the sport; Clemens has more strikeouts than all but two others. Yet they didn’t make the cut.

Their decade-long snub came for a simple reason: performance-enhancing drugs. Both men were linked to steroids, and both faced federal perjury charges for their denials of having juiced. Both also had late-career surges that now look artificially enhanced, with Bonds putting up some of the most eye-popping numbers in baseball history in his late 30s.

But their sins must be put in context. The two men had Hall of Fame résumés even before there was the slightest hint that they’d cheated. And Bonds and Clemens used PEDs in the middle of what was a Wild West era in the sport during which drug-testing didn’t exist, as baseball tried to recover from a season-canceling strike in 1994 by serving up a barrage of home runs. The era was immortalized in 1998, when Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa captivated the country with their home-run chase. (Both set single-season records, both used steroids, and neither has come close to being voted into Cooperstown.)

It should be said that even once baseball cracked down, beginning in the mid-2000s, players continued to cheat. Manny Ramirez, the best pure hitter of his generation, fell short of induction this year. He was suspended twice for performance-enhancing drugs. Alex Rodriguez, arguably the best shortstop of the past century, fell short as well. A-Rod has admitted to using performance-enhancing drugs throughout his career and was suspended an entire season for cheating.

The steroid era raises all sorts of difficult questions over what a Hall of Famer is. Does cheating with performance-enhancing drugs automatically disqualify a player? Does it matter if they did so when there was little testing and Major League Baseball was turning a blind eye to the issue? (Bud Selig, the commissioner responsible for the league’s laissez-faire attitude at the time, has since been enshrined himself.) At a time when the sport’s norms were collapsing, whom do we hold responsible, and why? That Bonds and Clemens have been denied entry to the hall, at least for now, hardly puts an end to these debates. But unlike the arguments of yore, this one feels both unpleasantly weighty and unsolvable.

And steroids aren’t the only knotty dilemma that voters now face. Ethical questions that were once ignored or swept under the rug are now front and center. Most notably, former star pitcher Curt Schilling has been snubbed by writers for being an alt-right troll. Schilling has tweeted about lynching journalists, promoted the political campaign of a neo-Nazi, and toyed with various conspiracy theories, from QAnon to Donald Trump’s false claims about the 2020 election. Slick-fielding shortstop Omar Vizquel has also suffered for his off-field sins. His vote was halved after he faced allegations not just of domestic violence by his estranged wife but of repeatedly sexually harassing an autistic batboy.

The Hall of Fame is already jam-packed with wife beaters and racists, including men who helped enforce segregation in the sport for generations. Is Schilling only being punished now because Ty Cobb and Steve Carlton didn’t have Twitter accounts, or should the generational reckoning with our country’s past cultural mores encompass baseball too?

The whole thing puts baseball fans in an unsatisfying limbo and leaves a void in the middle of the sport’s history. The only player to be inducted by the writers this year was David Ortiz, a devastating slugger for the Boston Red Sox who himself faced questions about his ties to performance-enhancing drugs over a drug test in 2003. (Ortiz disputes the test’s findings, and his best years came afterward.) He was the third-best former Red Sox player on the ballot with links to PEDs — Clemens and Ramirez were both better.

When the sport has failed so totally as an institution, when we have to parse for ourselves what was really bad cheating and what was just sort of bad, and when the Hall of Fame can’t really settle these admittedly impossible questions for us, it destabilizes the certainties of a century. Iconic figures like Babe Ruth and Willie Mays are succeeded by the muddied legacies of Bonds and Rodriguez, and we are left to judge their careers on our own with little confidence about what to trust or believe.

This is all depressingly familiar. A cycle of institutional failures has helped divide Americans to the point that the definition of truth is up for debate. It would be nice if baseball could provide a respite from all this. But now we can’t even agree on when a home run is just a home run.