As someone who spent months before the 2020 election warning that Trump was planning an election coup, then had to watch and write about his efforts that were finally foiled on January 6, 2021, I felt the anniversary of that day brought back in sharp relief bad memories that had never really faded. I realized that the fire we avoided last time might in future require more than a beefed-up Capitol police corps or resolute judges or a smattering of responsible Republicans. Like my colleague Errol Louis, I accepted that we might each need more of a personal commitment to democracy than just a willingness to vote and hope for the best.

But the most galvanizing January 6 meditation yet came in a New York Times op-ed by election-law expert Rick Hasen. This sober analyst of developments threatening the right to vote and subverting impartial election administration is clearly convinced that one of our two major political parties has sufficiently abandoned the causes he holds dear that they have gained a veto power over any remedial action in Washington and many crucial states. This leaves Democrats and the remaining responsible Republicans with few options going forward, particularly since the power they do hold in Washington and in the states may soon be significantly diminished.

Paradoxically, that means Democrats cannot afford to spurn any Republican efforts to help them prevent a 2024 coup. Hasen writes:

A coalition with the minority of Republicans willing to stand up for the rule of law is the best way to try to erect barriers to a stolen election in 2024, even if those Republicans do not stand with Democrats on voting rights or other issues. Remember it took Republican election officials, elected officials, and judges to stand up against an attempted coup in 2020.

It’s understandable that Democrats distrust the feelers some Republicans are putting out for cooperation on legislation to fix the Electoral Count Act of 1887, the hazy and confusing law that Team Trump tried to exploit to overturn Biden’s victory with the help of a mob. If the offer comes with the precondition of Democratic abandonment of voting-rights legislation, it may rightly be rejected. But at some point, accepting just enough Senate Republican help to close off one avenue to a stolen 2024 presidential election may be vital for Democrats, unfair is it may seem from a partisan point of view.

A more vexing problem, however, is what happens if the stolen election attempt occurs not in Washington but in the states. That’s where Trump is busily working to install loyalists in key election offices and where he may expect better and quicker complicity from Republican state legislators who could be in a position to control the certification of presidential electors. Hasen offers a specific scenario:

What happens if a Democratic presidential candidate wins in, say, Wisconsin in 2024, according to a fair count of the vote, but the Wisconsin legislature stands ready to send in an alternative slate of electors for Mr. Trump or another Republican based on unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud or other irregularities?

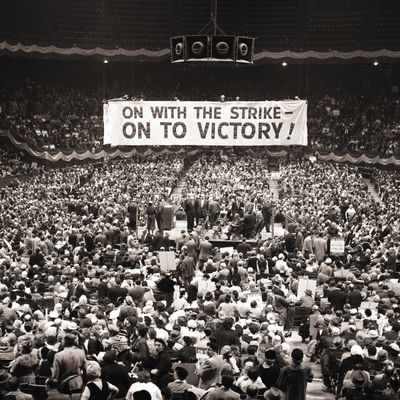

In that contingency, he argues, “widespread public protests made up of people of good faith from across the political spectrum” may be the only effective recourse. Indeed, says Hasen: “If the officially announced vote totals do not reflect the results of a fair election process, that should lead to nationwide peaceful protests and even general strikes.”

That last resort of labor protests, the general strike (a work stoppage not confined to any one industry or segment of the population), is not something that has ever been successfully deployed as a political weapon in the United States. The potential need to attempt one — even if it’s confined to a single locale like a state capital where a legislature is engaged in subverting a democratic election result — shows the gravity of the situation we may face in 2024 based not on paranoid fears but on what we witnessed this time last year and what we can see happening in MAGA-land right now. It’s not time to panic, but to plan, and to accept that the window for pursuing more conventional means to prevent a coup may be closing more rapidly than we think.