Most political observers assume Democrats are going to have some sort of setback in November. After all, the party controlling the White House has lost U.S. House seats in 19 of the last 21 midterm elections. In the two years that were an exception to this pattern, the president had job-approval ratings over 60 percent, while President Biden’s current job-approval average according to FiveThirtyEight is just 41.6 percent. Republicans’ Senate chances are iffier, but the odds are high that a red wave will have consequences up and down the ballot, particularly given the steady rise of straight-ticket voting in recent years.

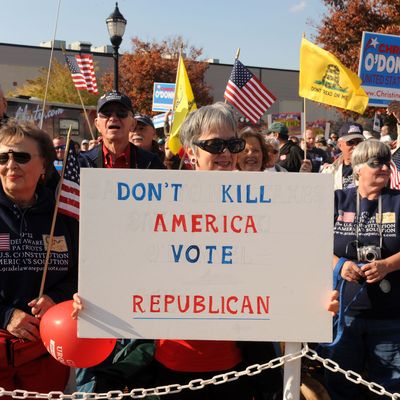

So exactly how bad could November 8, 2022, be for Democrats? Is the relevant precedent, say, 2010, when the Donkey Party lost a net 63 House seats, 6 Senate seats, 6 governorships, and 20 state legislative chambers? It’s tempting to think so. That year was the first-term midterm for Barack Obama, a new Democratic president who took office in worsening economic times and launched an ambitious agenda that was nearly undone by Democratic infighting and Republican obstruction. Energized GOP voters proclaimed themselves part of a grassroots Tea Party movement that would champion freedom and fiscal responsibility against the socialistic Democrats. Sounds pretty familiar, doesn’t it? Heck, Sarah Palin has even been in the news again.

But 2022 probably won’t be as bad as 2010 for Democrats due to one technical but very real issue: exposure. One big reason the 2010 losses were so enormous for Democrats is that the election was preceded by two straight Democratic wave elections in 2006 (which flipped control of the House) and 2008 (in which Obama posted the first comfortable presidential victory for either party since 1996). The president’s party entered the 2010 cycle with 256 House seats, 59 senators (soon to increase to 60 when Arlen Specter changed parties), and a majority of governors and state legislative chambers. There was simply an enormous amount of marginal political ground to be lost. Today Democrats control just 221 House seats, 50 Senate seats, and a decided minority of governorships and state legislative chambers.

The outcome in November, even if Democrats do poorly, is more likely to resemble the 2014 elections, when they had significantly less exposure to losses. Even though their share of the national House popular vote (51.4 percent) was nearly as high as it was in 2010 (51.7 percent), Republicans gained only 13 House seats in 2014. They also netted only two governorships (though they did flip another 10 legislative chambers). The big Democratic setback in 2014 was the loss of the Senate, which happened mostly because the group of Democratic senators up for reelection that year had benefited from landslide conditions in 2008 and five of them retired. The Democratic Senate landscape in 2022 is positive or at least neutral, and it’s Republicans dealing with five Senate retirements.

But if you want a more precise analog in the recent past to where Democrats stand today, along with a reminder that strange things can happen between elections, the cycle to look at is 2002. Exactly like Democrats at this moment, Republicans under George W. Bush came out of 2000 with 221 House seats and 50 senators. The fragility of the GOP trifecta was dramatized on May 24, 2001, when Republican Senator Jim Jeffords decided to switch parties, handing control of the upper chamber to Democrats. On September 10, 2001, George W. Bush’s job-approval rating was 51 percent and on a steady downward trajectory. It sure looked like the GOP was headed for a devastating midterm, probably including the loss of both congressional chambers. But then 9/11 happened. Bush’s job-approval rating shot up to 90 percent after the attacks, and Republicans made small but still very unusual midterm gains. It goes to show: History has some clear lessons about midterms, but never bet the farm on any election outcome until the votes have been cast.