This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

I’m nearly two hours into an interview with Sam Rivera, who runs one of America’s first supervised-drug-consumption sites, when a voice cuts abruptly through his serene, incense-filled office.

“Code Blue,” a radio crackles. Two floors below me, someone has just overdosed.

It is the 80th overdose in just five weeks between two sites operated by the nonprofit group OnPoint NYC; this one is in East Harlem, the other in Washington Heights. “We are like an ER here,” says Rivera, the group’s executive director. “Just wait here. Don’t leave the room,” he says and hurries out the door to investigate.

Less than 30 minutes later, he’s back, sweat glistening on his forehead. He tells me that a young woman who had injected fentanyl started to have trouble breathing and began to lose consciousness. The staff gave her oxygen and, sensing that wasn’t enough, opted for a small shot of the overdose-reversal drug naloxone, which almost instantly revived her. Within ten minutes, she was on her way out the door. He clasps his hands studded with rings as he thinks what might have happened if she overdosed outside instead of under OnPoint NYC’s supervision. “How could anyone object to saving lives?” he asks.

The site opened during the waning days of Bill de Blasio’s tenure as mayor; he entered office as fatalities exploded across the country due to an influx of illicitly made fentanyl into the U.S. heroin supply. The facility in Harlem opened on November 30, a campaign promise that de Blasio waited until the very end of his term to fulfill. The case for supervised consumption is straightforward: As Rivera said, it saves lives, and at a moment in which overdoses claim the lives of more than 100,000 Americans per year — 2,243 in the city alone by last count — the government can’t stand in the way of any solution no matter how controversial.

While de Blasio deserves credit for harnessing the political will, albeit late in the game, to green-light the opening of OnPoint NYC, it is really the accomplishment of a handful of dedicated activists and their allies in city government who spent more than a decade advocating for supervised consumption — sometimes over the objection of their own peers — before taking matters into their own hands.

“You know, I get a lot of credit for being the first,” says Rivera, his eyes filling with tears. “But it’s hard to take credit for that when I know a lot of brothers and sisters died trying to open these.”

At first glance, OnPoint NYC’s Harlem site may look like a resource center for the homeless and transient, with a television and a computer, laundry machines, and two showers. Deeper inside, however, behind a single locked door, is a room with eight brightly lit stainless-steel booths, four on each side. Rivera and I wait behind a patron to get buzzed in. The facility has strict limits on how many people can be inside the room at one time. As we enter, a man in one booth is preparing a syringe. To his right, another man has just finished injecting and is now dancing in place to music only he can hear. Large mirrors, which face the center of the room, let people who inject here find veins under the arm or in the neck and help staff members observe their faces for signs of overdose.

Along the back wall, two doors open into separate rooms where people can smoke crack or other drugs. Currently, only one person at a time is allowed in each room, to discourage drug sharing. But demand has been so high that the facility plans on combining the rooms and adding a plexiglass window to accommodate multiple people at once. Posted outside the doors are two crash carts stocked with naloxone, pulse oximeters, and laryngeal tubes for opening restricted airways. Rivera says his staff is trained to identify overdoses early, so for most people, only oxygen is needed. All the overdoses at OnPoint’s two facilities have been successfully reversed, and only one — an individual who suffered a seizure — required a call to 911.

Staff provide clean needles and other paraphernalia in the supervised-injection room.

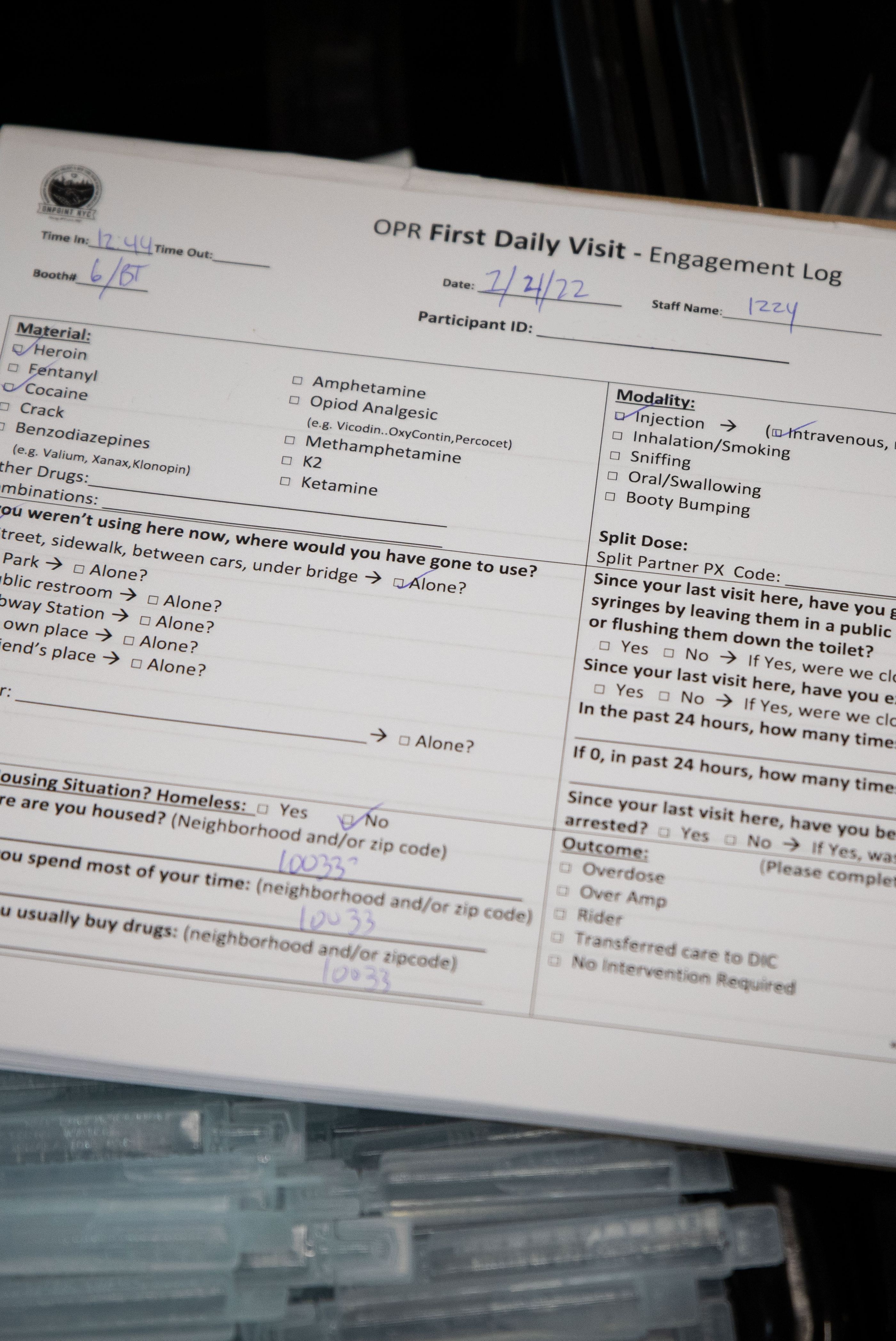

Clients fill out an intake form upon arrival.

Staff provide clean needles and other paraphernalia in the supervised-injection room.

Clients fill out an intake form upon arrival.

Users have to bring their own drugs, but they may choose from an assortment of paraphernalia that includes glass stems and Chore Boy for smoking crack, straws and plastic cards for cutting and snorting drugs, and, of course, syringes in a variety of sizes and gauges. First, though, they must answer a short anonymous survey about which drugs they plan to use and in what quantity, the places they typically go to inject, and how they dispose of syringes when they use outside the facility. Given that supervised consumption is such a controversial issue, keeping data is critical to both substantiating proponents’ claims about its effectiveness and creating a road map for other cities to follow. Rivera says he’s been receiving almost daily calls from city leaders across the U.S. asking for advice.

A middle-aged man who said he came from Staten Island rattles off answers to a young staffer named Rayce, a slender young man with ringlets of long brown hair that hang beneath his shoulder blades, before washing his hands and choosing a syringe, tourniquet, and cooker for his heroin. Rayce led him to a booth close to the entrance and wheeled over the privacy screen that the man had requested.

“In the beginning, I think people were more shy or whatever, and a lot more people asked for the screens,” says Rayce. “But now that people feel more comfortable, we don’t pull the screens out as much.” The staff insists that reducing the shame and self-stigmatization associated with drug use — being greeted with a smile and without judgment — can help users begin the road to healing and self-care. “Many times, people finish up here and think, You know what? I’m gonna go see the on-site nurse and get tested for hepatitis C,” Rivera says.

The sites also serve as a means for people who want to reduce their drug use or quit altogether. The day before my visit, according to Rivera, a man came to use but opted to see the doctor instead. “He had had a good experience with family over the recent holidays, brought them here to see the place, and that day he decided he was ready to go to detox,” Rivera says. OnPoint staff called for a van to take the man to treatment.

The man from Staten Island prepared his shot from behind the screen as Rayce finished jotting answers on the questionnaire. “Do you need help tying off today?” he asked with the attentiveness of a bartender. “How about water?” About ten minutes later, he indicated he was done. Rayce removed the screen and told him to leave his trash on the table. With that, the man thanked the staff, put on his brown leather jacket, and stepped out into the cold afternoon air.

When Louis Jones started using heroin in the ’70s, sometimes he would duck between cars or in an alley, relying on other users to keep lookout as he prepared his heroin in the cap from a bottle of cheap wine he carried with him. It was common for shooting galleries to recycle injection equipment, sometimes renting reused needles out of containers full of water that were tinged pink from blood. In 1986, a public-service announcement about HIV caught Jones’s attention, and he decided to get tested. Two weeks later, a nurse took his hand and told him he was positive for the virus. “I said, ‘Hell no!’” he recalls. Jones spent the next three years refusing to accept his diagnosis until a friend took him to his first meeting of the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP. “I knew right away I was in the right place,” he says. He began attending ACT UP meetings regularly and participating in its protests.

In the late 1980s, in violation of a state law against distributing drug paraphernalia, ACT UP started passing out clean needles in Manhattan. The act of civil disobedience led to the arrest of eight activists on the Lower East Side. The following year, the state followed ACT UP’s lead and authorized the opening of five syringe-exchange programs in the city. Thanks almost entirely to the work of these exchanges, less than 5 percent of intravenous drug users today have contracted HIV/AIDS, according to state data.

Jones took retroviral meds for his HIV and endured a six-month course of interferon that cured his hepatitis C. His transition from addict to activist now complete, Jones, who is now 65, channeled his rage into advocacy and eventually started a Brooklyn-based drug-user union, composed largely of people of color like himself, to advocate for racial equity in the treatment of HIV and hepatitis C. He called it Voices of Community Activists & Leaders, or VOCAL-NY, which would become one of the most aggressive proponents of social justice for drug users and of supervised consumption. Along the way, he met Rivera, who, like Jones, brought the message of harm reduction to the back alleys and underpasses, where many others feared to go. Recently, he called to tell me he had a new job at OnPoint NYC, just a short distance from where he contracted HIV.

“It’s hard to believe it, man, to think how far we’ve come,” says Jones in a thick Brooklyn accent. “This whole area was surrounded by shooting galleries. And now we’re helping people live.”

A client is supervised as he prepares to use drugs.

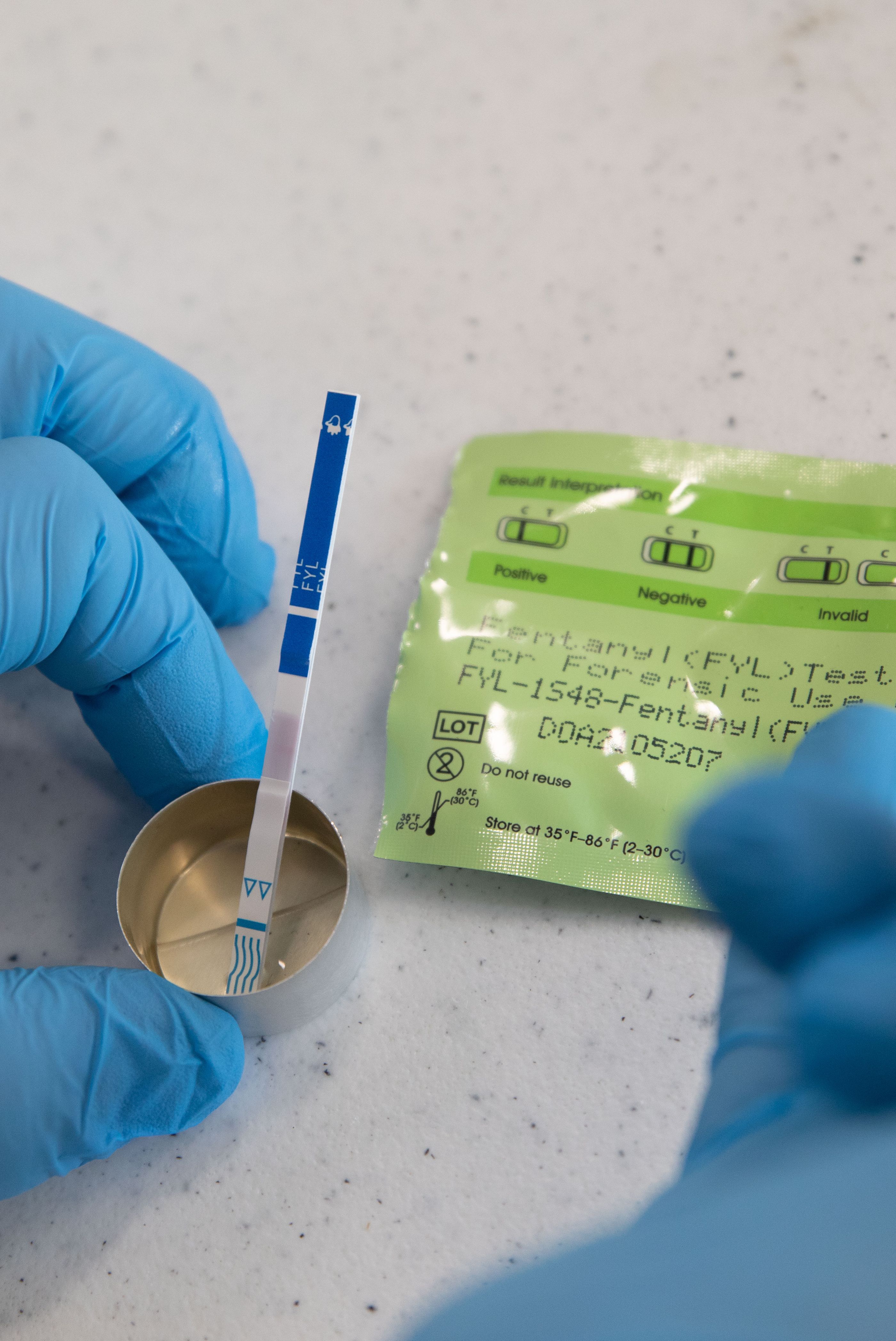

Drugs are tested for fentanyl to curb overdoses.

A supply of Narcan nasal spray, an overdose-reversal drug.

A supply of clean needles.

A client is supervised as he prepares to use drugs.

Drugs are tested for fentanyl to curb overdoses.

A supply of Narcan nasal spray, an overdose-reversal drug.

A supply of clean needles.

In 2009, Jamie Favaro was handing out clean needles as the head of the Washington Heights Corner Project, a syringe-exchange program, when she noticed that more people were overdosing inside the organization’s building and in alleyways and parks around the site. By then it was an open secret that patrons of the city’s syringe exchanges were getting high in the bathrooms. Some of the sites tacitly tolerated on-site drug use, while others tried to stop it by installing blue lights in bathrooms to make it harder for users to find a vein or by closing bathrooms to clients altogether.

Favaro, however, set about making them more accessible. She modified the doors to swing out instead of in and installed locks that could be opened from outside so that staff could intervene in the event that someone overdosed inside. Within a few years, other syringe exchanges across the city followed WHCP’s lead and modified their bathrooms. In 2017, I saw patrons at a Brooklyn facility patiently waiting to use a bathroom to inject. Inside was a sharps container for used needles and a metal shelf for placing injection supplies. The door could be unlocked remotely by staff, and there was an intercom to check in on people who seemed to be taking too long.

Quietly and without the permission of authorities, these harm-reduction activists began laying the groundwork for today’s supervised-consumption facilities, risking criminal charges if they were caught. “Our program operated as an unsanctioned, street-based syringe-exchange program for two years before we became legal,” Favaro says. (Today, it operates as OnPoint’s other supervised-consumption site.)

The same year that Favaro modified WHCP’s bathrooms, New York City’s Health Department published a report that found that more than half of the city’s IV drug users were reusing syringes and that raised the “politically controversial” idea of “establishing safe injecting facilities” in the city. There were no such sites in the United States, but those in favor of the idea could point to the success of a similar program in Vancouver, which had been operating a supervised-consumption facility for six years. Early research showed that the site led to a decrease in fatal overdoses, was associated with reductions in crime, and lessened the burden on first responders.

“We had a plan and everything but were prevented from executing it because we did not have City Hall sign off,” says Denise Paone, the senior research director at the Health Department who co-authored the report, referring to what she said was a lack of political will by de Blasio’s administration.

Even as record numbers of Americans began dying of drug overdoses, within the framework of America’s zero-tolerance drug policy, the idea of running an organization in which people openly inject illegal drugs was still a nonstarter, even for many progressive drug reformers.

As deaths kept rising, the vanguard of the city’s harm-reduction community felt it was time to turn up the heat. “Having conversations with harm-reduction colleagues was helpful early on, but it wasn’t going to move the needle fast enough,” says Taeko Frost, who replaced Favaro as executive director of WHCP. So, in 2014, the organization tried to force de Blasio’s hand by revealing to the public that it was already running a quasi supervised-consumption site — and had been since 2009. When the story ran at BuzzFeed News, it sent shock waves throughout the harm-reduction community and inside city government. “That article caused great worry on the part of the city,” says Paone, adding that there was consensus among city officials that what the organization had been doing was illegal.

“People have always injected in our bathrooms, but you kind of looked the other way,” says Joyce Rivera, who launched St. Ann’s Corner of Harm Reduction in the Bronx after years of running an illicit needle exchange. “We were afraid we could all have our waivers pulled,” she says, referring to the state permits that allowed syringe-exchange programs to operate. To everyone’s surprise, however, nothing happened. “No one inspected or regulated or defunded anything,” says Matt Curtis, the then–policy director at VOCAL-NY. “Eventually, we realized they were allowing us to continue without interference.”

Overdoses kept rising, and the harm-reduction activists pushed for more than just a lack of interference; they wanted city-funded, fully legal supervised-injection sites. In 2017, they began lobbying for a law authorizing supervised consumption in New York and got City Council to earmark funds for a feasibility study on supervised consumption by Paone’s team at the Health Department. Then they hit another roadblock: de Blasio, who withheld the study for two years after it was completed, perhaps fearing the results would force his hand to endorse the idea ahead of his presidential run and without Governor Andrew Cuomo’s support. Finally in May 2018, more than 100 protesters descended on City Hall to call for the study to be released. Nearly a dozen people were arrested, but the next day, de Blasio announced his support for four pilot supervised-consumption sites, which the report found could prevent up to 130 overdose deaths annually and save the city up to $7 million a year in health-care costs alone.

It would take nearly four years before the sites could open, though. In Albany, Cuomo’s health department was cool on the idea, according to Paone. In Washington, the Trump Justice Department was suing the nonprofit group Safehouse to prevent it from opening a supervised-consumption site in Philadelphia, claiming it would violate a federal statute known as the “crack-house law,” which makes it a crime to operate a facility for the purpose of using illicit drugs. The DOJ indicated it was prepared to file charges carrying a penalty of up to 20 years in prison against anyone who opened such a site. “Would I have done this with Trump in office?” says Rivera. “Hell no!”

By all accounts, Cuomo’s resignation last summer removed the final obstacle for de Blasio to green-light OnPoint NYC. In September, Rivera and his colleagues quietly began the final preparations to bring OnPoint NYC online. “All through November, we were getting deliveries of supplies for the overdose-prevention room. We told the shipping agency to write Church on the boxes,” he says. “Today, some still call the overdose-prevention room ‘the church.’”

To date, the OnPoint NYC sites have saved more than 100 lives. Despite worries, local opposition has been limited. There was one demonstration in December, organized by the Greater Harlem Coalition, a group that opposes the concentration of drug treatment facilities there, but little since. So far, Mayor Eric Adams is supportive of the sites, announcing on social media that he wants to see even more open. But the hope for the city to set a broader pattern may not be so bright. Governor Kathy Hochul and the lawmakers in Albany have not endorsed supervised consumption, and the Biden administration might be reluctant to embrace any drug policy that appears radical after the backlash it faced over a story falsely claiming the Feds were providing crack-smoking kits as part of a harm-reduction program. And the law used by the Trump administration against Philly’s sites remains on the books.

Even if the concept is taken up elsewhere across the city or the country, its reach is inherently limited. The city’s facilities cater primarily to the homeless and transient, not people who use and die at home, such as Michael K. Williams, who was killed by fentanyl-adulterated heroin in his Brooklyn apartment. Stronger local opposition than what materialized in Harlem would certainly keep sites out of many cities and neighborhoods and away from people who might not otherwise travel a long distance to use. That the man from Staten Island came to Harlem suggests he probably purchased his heroin nearby. Ultimately, so long as the drug supply is tainted, every dose is a potential killer no matter where it’s taken.

Back in his office, Rivera waves off the potential obstacles to come. “We’re not a new service; we are an improved service,” he says. “We’ve been here. We are your neighbors. We are part of the community,” Rivera says. “We’re not going anywhere.”