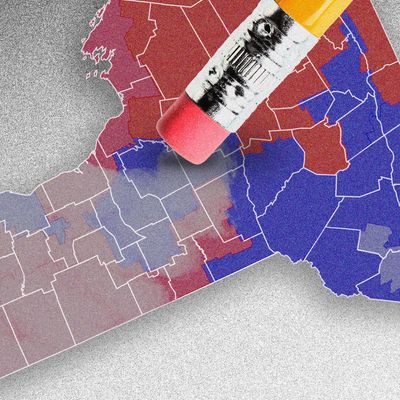

This week, New York’s Democratic Party approved a redrawn congressional map that could net it three more seats in the House of Representatives and cut the state’s Republican representation in half. Governor Kathy Hochul signed the new map into law the following day, along with new maps for the state Senate and Assembly districts.

Democrats currently hold a thin 222-212 majority in the House, but the tendency for parties in power to suffer midterm losses — plus less than ideal approval ratings for President Joe Biden — has the party on edge. Because Democrats hold a legislative supermajority in New York, it was one of the few states in which the party could take control of the redistricting process and slightly improve its overall midterm prospects. The aggressive effort to do just that has prompted accusations of hypocrisy toward Democrats, who have frequently campaigned against gerrymandering. Party officials say they are merely matching an example set by Republicans across the country.

New York Republican State Committee chairman Nick Langworthy described the newly drawn districts as “textbook filthy, partisan gerrymandering” and voiced the possibility of a court challenge, though it appears one is unlikely to succeed.

“We are reviewing all of our legal options to protect the voices of millions of New Yorkers,” he said.

Not long after Hochul signed off on the new district lines, a lawsuit was filed in the Steuben County Supreme Court alleging that the new maps are unconstitutional.

The changes are wide-ranging. Congresswoman Nicole Malliotakis, a Republican, represents the 11th Congressional District, which encompasses all of conservative Staten Island as well as Bay Ridge and Dyker Heights in Brooklyn. The new map links Staten Island with liberal neighborhoods like Park Slope and Sunset Park, drastically changing the district’s demographics. This favors Democrat Max Rose, the former congressman who previously held the seat before losing to Malliotakis in 2020 (also, possibly, Bill de Blasio).

“This is a blatant attempt by the Democrat leadership in Albany to steal this seat, even after New Yorkers voted twice by ballot referendum for nonpartisan maps,” said Rob Ryan, a spokesman for the Malliotakis campaign, in a statement to Intelligencer.

Outside the city, the seats currently held by outgoing Republicans Lee Zeldin and John Katko were already seen as prime pickup opportunities. (Zeldin declared his candidacy for governor in early 2021, while Katko announced in January that he would be retiring from office.) But both congressmen’s districts have also been redrawn, with Zeldin’s First District on Long Island extending into Democratic areas and Katko’s 24th District folded into the 22nd District, which will include the blue cities of Ithaca and Syracuse.

Another Republican congresswoman, Claudia Tenney, is opting to run in a new district entirely after a large portion of her 22nd District was redrawn into the 19th, currently represented by Democrat Antonio Delgado. Tenney will try her luck in the 23rd District, where the region’s current representative, Republican Tom Reed, previously announced his plans to retire.

In 2014, New Yorkers backed a ballot proposal that would amend the state constitution and establish an independent redistricting commission responsible for redrawing state and congressional districts based on Census results. (In 2020, the state lost one seat in the House just barely.) In January, the ten-member panel submitted two maps to the state legislature after members failed to come to an agreement on a single proposal. The legislature rejected both maps and gave the panel additional time to present a new draft. But the panel reached an impasse, allowing the state’s legislative task force to step in and submit its own lines. State lawmakers moved quickly, citing the fact that candidates will have to begin petitioning to run for districts in March.

Steven Romalewski, director of the mapping service at the City University of New York’s Graduate Center, said that the state legislature’s actions are consistent with the law.

“I think there’s a big difference between what the perception is of what the voters voted on versus the reality. The constitutional amendment, for good or for ill, explicitly gives the legislature the ability to do exactly what they’re doing now, and that was part of the constitutional proposal that the voters approved,” Romalewski said.

There has also been criticism that state lawmakers didn’t provide enough time for public input into the creation of the new maps. The independent redistricting commission, by contrast, held public hearings and allowed members of the community to submit comments on the proposed maps.

“Now you have these maps that are drafted by the legislature in the space of a week without any opportunity for the public to have any input,” said Susan Lerner, the executive director of Common Cause New York. She called the commission “fatally flawed” from the beginning.

In Lerner’s view, for a redistricting commission to be truly independent, it has to be citizen-led and outside the purview of legislative officials.

“It’s virtually irresistible for politicians to be able to benefit themselves and to lock in their position. The pencil’s got to be taken out of their hands,” she said.

Independent commissions have the final word on redistricting in states like Michigan and California. And in some places, such as Pennsylvania, state courts have stepped in to take control after determining that legislators’ maps were too partisan. But it looks likely that in New York, raw politics will determine the lay of the land for the next ten years.