It was evident from the start that Attorney General Merrick Garland, like Joe Biden, was eager to move on from what happened under the Trump administration without much retrospective legal analysis, from the former president’s own potentially unlawful misconduct to the problems within the Justice Department itself. As misguided and unfortunate as that approach may be, Garland has mostly succeeded in leaving the past in the past. But there have also been times when this approach has forced the current administration to be at least partially complicit in the previous one’s misdeeds.

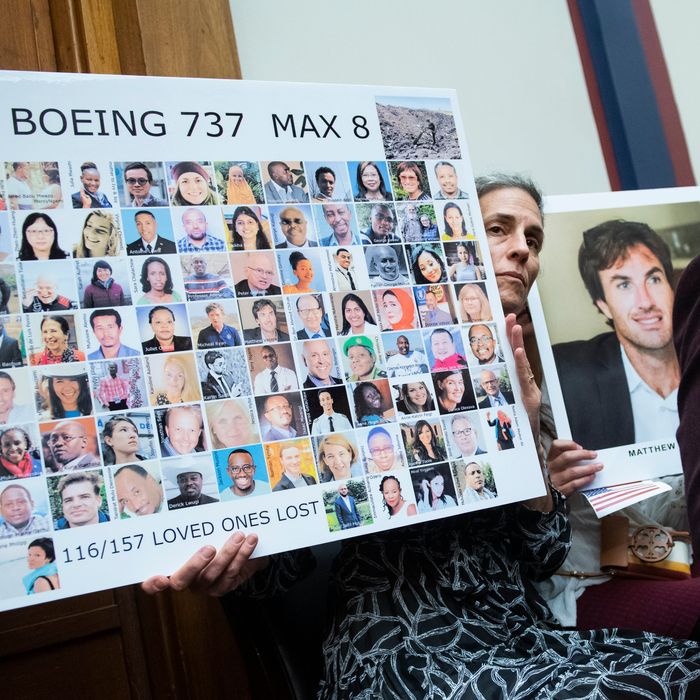

Some of those legal battles have prompted public outrage, like the Justice Department’s continuing defense of Trump’s right to defame E. Jean Carroll, as well as its ongoing effort to maintain the secrecy of an internal memo about the Mueller investigation even after a judge accused department lawyers last year of intentionally misleading her. The list grew a little longer a week ago. Last Tuesday, the Justice Department opposed a legal effort by some of the families of the 346 people who died in the Boeing 737 Max crashes to revisit the department’s infamous settlement with Boeing in the final weeks of the Trump administration.

The Boeing deal, which ended a criminal investigation resulting from the crashes, was one of the most ill-conceived and widely criticized corporate criminal settlements in modern history — an extraordinary feat of corporate deal-making by Boeing in which the company effectively purchased an official government exoneration of the company’s executives in exchange for allowing the government to take credit for a bunch of money that the company was already going to pay anyway. (As I have noted previously, I worked in the Justice Department office that conducted the Boeing investigation and completed the settlement and also know several people on the team, but I was not involved in the investigation.)

The Justice Department’s settlement with Boeing took the form of a “deferred prosecution agreement,” in which the department filed a criminal charge against the company in federal court that it is holding in abeyance pending the three-year term of the deal. The underlying criminal conduct concerns a relatively low-level Boeing employee named Mark Forkner who allegedly provided “incomplete and inaccurate” information about the 737 Max’s flight-control system to the Federal Aviation Administration. But if the company abides by the provisions of the agreement — most importantly, paying a monetary penalty and not committing another crime — the government will dismiss the charge and Boeing will avoid the most serious “collateral consequences” of a criminal conviction, which can, among other things, affect a company’s ability to do business with the federal government, a vital source of Boeing’s business.

The Boeing settlement had a top-line figure of $2.5 billion, but about two-thirds of that was money that went to airlines — money that Boeing had, in fact, already set aside to pay them. Less than one-tenth of the total payment ($243.6 million) was an actual fine, which appears to have been generated by using one of the most charitable interpretations possible of the relevant guidelines, while another $500 million was set aside as a victim-compensation fund. Structurally, at least, perhaps the strangest part of the deal was a provision in which the government stated that “the misconduct” at issue “was neither pervasive across the organization, nor undertaken by a large number of employees, nor facilitated by senior mismanagement” — an unprecedented affirmative exculpation, according to experts.

The deal was heavily criticized, but it did not attract the widespread public attention it deserved since, in a perverse accident of timing, the settlement was announced the day after the siege of the U.S. Capitol on January 6. The meaning of the news, however, was not lost on the outraged families of the victims of the 737 Max crashes. Michael Stumo — whose daughter died in the crash of Ethiopian Airlines Flight 302 — said that the families “erupted in anger, shock, and renewed grief” when they heard about the settlement, while Chris Moore, another father who lost his daughter in the crash, described it as “a slap in the face.” Others decried the outcome as well. Peter DeFazio, the Democratic chair of the House Transportation Committee who led an investigation following the crashes, called the deal “pathetic” and a “slap on the wrist” that was “an insult to the 346 victims who died as a result of corporate greed.” Democratic Senator Richard Blumenthal called the settlement a “disgrace.” And a well-regarded expert on corporate crime at Columbia Law School said the deal was “an egregious case and one of the worst deferred prosecution agreements I have seen,” and accused the government of “serving its own interest by inflating the size of the settlement” through the payments to airlines, which were going to happen regardless of any settlement with the DOJ.

Ordinarily, that would be the end of it — even bad government settlements are pretty much irreversible — but in December, 15 families filed an unusual objection to the settlement in court on the theory that the government had failed to comply with a statute that requires it to confer with crime victims before completing a formal resolution, such as a plea agreement, with the offender. As Stumo wrote in an op-ed last month, the families claim that the department opted to “deliberately conceal its investigation and covertly negotiate with Boeing toward a favorable, deferred prosecution agreement” — citing, in particular, an episode in early 2020 in which someone in the department’s Victims’ Rights Ombudsman office incorrectly told a representative of the families that there wasn’t even an active criminal investigation. The families’ concerns, however, are more than procedural. They have taken issue with the fact that, under the deal, Boeing was able to avoid a criminal conviction or a trial that may have highlighted a broader array of questionable conduct within the company, particularly among Boeing executives.

After the filing, the families requested a personal meeting with Garland to press their case — asking him, as Stumo put it, to “fully investigate the sweetheart deal that allowed Boeing to skate through with little punishment” — in an apparent effort to resolve the situation without the need for a potentially long and messy court battle. The families got that meeting in late January, and the presiding court, evidently hoping that the government might work out some sort of agreement with 15 families who have already suffered unfathomable losses, stayed the proceedings. At the meeting, according to what participants told the Associated Press, Garland “expressed sympathy to relatives who spoke” but “made no promises or substantive comments on the case.” That is presumably because, however gracious it may have been for Garland to grant the audience, the DOJ had already decided to oppose their efforts in court, which is what it proceeded to do less than two weeks later.

Standing alone, all of that would have been merely somewhat distasteful, but the Justice Department’s court filing is a remarkable specimen of legal writing — indelicate at best, at times bordering on offensive — that is so at odds with the somber and earnest tone Garland strives to maintain in public that it is difficult to believe that he saw it. The department’s principal contention is that the families are not actually victims of a crime since prosecutors have never specifically claimed that the alleged misconduct of the Boeing employee, Mark Forkner, actually caused the crashes. The department proceeds to apologize in the filing “for not meeting and conferring with” the families before the deal, “even though it had no legal obligation to do so,” and claims that even though “such consultations would not have changed” the outcome, “there is a chance that earlier consultation may have been able to provide these individuals with insight into the Government’s approach toward corporate criminal prosecution and this case.” This was a classic “I’m sorry, but …” non-apology coupled with a bit of condescension that is all the more striking because the families thus far seem to have a perfectly fine grasp of how corporate criminal investigations work.

Elsewhere, the filing suggests that the families have failed to fully appreciate the benefits that the government obtained for them in the form of the $500 million compensation fund — as if better than nothing was tantamount to as good as it should have been — while wholly ignoring the government’s exculpation of Boeing’s senior management. The DOJ filing also seems to accuse the families of strategically waiting to object until “after virtually all of the crash victims’ beneficiaries fund payments had been made” — a particularly gross implication considering that one victim’s widow has explicitly said that she refuses to accept any “blood money” from the settlement.

The implication that the families misunderstood the government’s position on the relationship between Forkner’s alleged misconduct and the crashes is extremely disingenuous. While it’s true the government has never specifically alleged that Forkner caused the crashes, the government has also gone out of its way to strongly imply as much. The agreement with Boeing packaged the allegations regarding Forkner into a global resolution of the investigation into the crashes. The press release announcing the deal talked at length about the crashes and the passengers who died while also claiming that Forkner had “impeded the government’s ability to ensure the safety of the flying public.” And the indictment against Forkner contains a section on the crashes even though the government does not need to establish anything about them in order to prevail on the charges that it brought against him, which turn on whether he intentionally misled regulators.

As it happens, the government’s effort to have it both ways last year — to charge relatively low-level and possibly inconsequential misconduct by Forkner while also suggesting that it had successfully completed a major criminal investigation into the crashes — has now also imperiled the case against Forkner, which is being overseen by the same judge who is presiding over the corporate settlement. That is thanks to an entirely different but similarly unprecedented development that unfolded in parallel in December, when it came to light that that three FAA officials had privately accused prosecutors on the case of making Forkner a “scapegoat” and of bringing an “incorrect and misguided” case that was premised on “many errors in fact.”

The FAA officials sent the Justice Department a lengthy PowerPoint presentation within weeks of the Forkner indictment late last year to object to the case against him. According to excerpts of the presentation provided in court papers by the defense, the FAA officials said that the crashes were caused by “an ENGINEERING issue that Mr. Forkner was neither qualified, expected, nor responsible for,” argued that a conviction of Forkner would result in a “miscarriage of justice,” and accused the government of misrepresenting the purported evidence against him.

The Justice Department appears to have been deeply concerned about the potential impact of the officials’ presentation on the case, because instead of immediately disclosing it to the defense, which is what should have happened, the government sat on it for a couple of weeks until after they could interview one of the authors. In that interview, according to a government court filing, prosecutors “corrected” the witness’s “misimpression” that they had alleged that Forkner’s conduct had actually caused the crashes, and the witness “conceded that he had no contemporaneous knowledge” of Forkner’s conduct.

This sequence of events suggests the unseemly possibility that the government sat on the presentation until they could meet with the witness, before the defense could, in order to extract concessions from him that they could then use to cross-examine him at trial if he testifies. This is not improper as an ethical matter, but it is also not the level of scrupulousness you hope to see when the government is actively trying to send someone to prison. All of this has set off a major — and potentially decisive — pretrial fight between the government and Forkner that may turn on the same question at issue in the families’ dispute over the settlement with Boeing: Did the government cross a line by suggesting that Forkner himself caused the crashes?

In the wake of the revelations about the FAA officials’ PowerPoint, the government told the court that it will not “argue or even suggest” that Forkner caused the crashes, and has asked the court to preclude Forkner from defending himself at trial by claiming that he has been improperly scapegoated by the government. It remains to be seen how the court will rule, but it is not often that representatives of a victim of alleged criminal misconduct — in this case the FAA — accuse prosecutors of having charged the wrong person.

Indeed in the past, when it appears that the government may have charged someone to shoulder the blame for a much larger episode of corporate malfeasance, juries have refused to convict — which is what happened in the wake of the 2010 BP oil spill. (In fact, one of Forkner’s lawyers represented a BP employee who was eventually acquitted at trial.) The judge recently dismissed two of the charges against Forkner — yet another significant setback — but even if he sides with the government on this separate evidentiary question, the defense will surely appeal the ruling if Forkner is convicted.

All of this seems to be trending toward more unpleasantness and frustration with the Justice Department’s handling of the Boeing investigation — now under the leadership of Garland. Even if the families were to prevail in their fight against the settlement and somehow invalidate key portions of the agreement — which very much remains to be seen — there does not appear to be anything that would prevent the government from executing the exact same deal with Boeing after “conferring” with the families. Furthermore, a moderate attorney general who is overly concerned with a narrow conception of “institutionalism” and continuity is probably the last person to do anything truly radical like try to scrap the whole thing, even if the court made that possible for him. Meanwhile, Justice Department prosecutors have done nearly a complete 180 on Forkner, and are now going out of their way to minimize his conduct in order to prevent their case from being tanked as a result of the department’s own self-promotional and misleading rhetoric in the final weeks of the Trump administration.

The whole mess is another in a long line of unpleasant inheritances for Garland, but it became his to manage when he took office last year. So far, it is not going well.