Unit 56D in Three Lincoln Center, a residential tower down the block from the Metropolitan Opera House, is a luxury three-bedroom condo valued at more than $3.2 million. It wraps around one of the tower’s corners, offering sweeping views of Central Park, the Hudson River, and the lower half of Manhattan. It’s empty now, but since 2004, the property has been owned by one of Vladimir Putin’s most high-profile defenders, Valery Gergiev, the director of Russia’s state-owned Mariinsky Theater.

Gergiev doesn’t quite fit our notion of a Russian oligarch, those titans of industry who command the country’s vast reservoir of natural resources. “In spite of being a pretty famous conductor, he’s small potatoes in the world of oligarchy,” said Gergiev’s former agent, R. Douglas Sheldon, who confirmed that Gergiev bought the apartment and signed over partial power of attorney to maintain it. But the case of Gergiev does shed light on the difficulties U.S. authorities face in identifying and seizing Russian assets as the Biden administration seeks to put the squeeze on Putin’s regime.

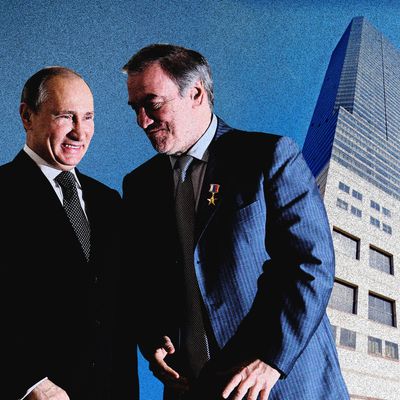

Gergiev has been friends with Putin since the early days of post-Soviet Russia. As the director of one of the world’s most storied opera and ballet houses — a place that debuted works by Tchaikovsky and presented Mikhail Baryshnikov — he has had a hand in softening Russia’s reputation in the U.S. and throughout Europe. His role in establishing Russia as a powerhouse of western culture was going well until recently, when Gergiev lost his positions in Munich, in Vienna, and at New York’s Carnegie Hall after he refused to denounce Putin’s invasion of Ukraine.

“He plays that propaganda role,” said Dmitry Valuev, who for the past year has been quietly hunting Russian oligarch money in the U.S. with a group of roughly 25 volunteers. Valuev — who discovered Gergiev’s apartment in public filings — became interested in the flow of Russian money in 2009, when the global economy was still recovering from the blowup of U.S. subprime mortgages. A surge in the cost of energy prices was filling up the state’s coffers — or, at least, that was where the revenue was supposed to go. “The economy was growing very fast in Russia at the time because of the oil prices, but in the meantime, we didn’t see any social change, we didn’t see any investment in infrastructure, we didn’t see that the government made attempts to make people’s lives better,” he said.

The mystery of what happened to all this money pushed him into a career tracking corruption in his home country, working on the Magnitsky Act Initiative to sanction foreign government officials, and organizing groups of émigrés in the U.S. for the Free Russia Foundation in Washington, D.C. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has amped up his efforts to find the places where Russian elites have parked their cash. Valuev said Gergiev’s holdings in New York have never been publicized prior to his group’s discovery, even as Russian law requires government employees to disclose their foreign holdings.

Russia and its companies, operatives, and citizens have already been the subject of an unprecedented series of global sanctions, but Valuev is pushing not just to freeze Russia’s assets — he wants to expose the vast amounts of wealth hidden throughout the U.S. economy just as prosecutors are looking to take control of them. Since the start of the invasion on February 24, French and German governments have seized superyachts, while President Joe Biden and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson have threatened to take the oligarchs’ property. These efforts have barely made a dent. Estimates of Russian offshore wealth top $1 trillion globally, but getting to any of it involves navigating webs of LLCs, many of which are headquartered in tax shelter states like the Cayman Islands.

Valuev and his “militia,” as he calls his volunteers, have found more than an estimated $450 million in assets belonging to Russian business and cultural leaders by trawling through public databases, deleted Russian news articles, and other pools of public information that can give clues to where Putin’s closest confidantes have stashed their money. They still have a long way to go: According to Transparency International, current and former Russian officials have owned 28,000 properties in 85 countries between 2008 and 2020. “We have not found everything here in the United States,” Valuev said. “We just found what was on the surface.”

That the world’s wealthiest people are hiding their money isn’t really a secret. Since George W. Bush signed the Patriot Act in 2001, the U.S. Treasury has exempted the real-estate industry from the kind of strict money-laundering controls that apply to, say, stock trading, meaning that buying a multimillion-dollar condo on Wall Street undergoes less scrutiny than buying shares on the New York Stock Exchange. While the Treasury has slowly required some disclosures for some real-estate purchases in large cities like New York and Miami, they only apply to all-cash transactions over $300,000 made through shell companies, and only require those disclosures from title companies — not the agents who are actually brokering the deals.

“Real-estate agents were expressly exempted from anti-money-laundering program requirements for reasons unknown some years ago,” said Ross Delston, an attorney who’s worked extensively on anti-money-laundering issues. “The National Association of Realtors has one of the best lobbying arms in Washington.”

Since the publication of the Panama Papers in 2016, what’s come into clearer focus has been how dark money has been used to reward those in power, including people like Sergei Roldugin, one of Putin’s closest friends. Economists Gabriel Zucman, Filip Novokmet, and Thomas Piketty estimated in a paper that, as of 2015, Russia’s offshore wealth was roughly equal to what was within the country, a direct cause of widening inequality in the country. “Corruption fuels instability,” said Shruti Shah, CEO of the Coalition for Integrity, which tracks international corruption. “What also has happened is a significant amount of reputation laundering that allows these oligarchs to have this veneer of respectability and allows them to infect democracies.”

If finding oligarchs’ assets is arduous, unleashing the federal government to take control of potentially thousands of properties across the country would require the kind of resources and interagency coordination that hasn’t been seen the early days of the war on terror. Already, that plan has begun. The day after President Biden threatened to hunt down oligarchs’ luxury apartments, yachts, and private jets, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced the formation of Task Force KleptoCapture, a joint operation between the Justice Department, the Manhattan U.S. Attorney’s office, and the elite criminal-investigation unit of the IRS to find and take control of the oligarchy’s assets.

Barring a declaration of war, the Feds can’t just take ownership of assets without going through a criminal or civil procedure, called a civil forfeiture, that proves funds used to buy them were laundered or came via an illegal source, said Delston — an expensive, labor-intensive process that can take years. Instead, what they can do is just take it and hope the oligarchs don’t put up a courtroom fight, which could give the government ownership in as little as six to nine months. “In order to seize, they just need a seizure warrant, which is virtually identical to getting a search warrant,” said Arnold A. Spencer, a former Assistant U.S. Attorney. Essentially, any prosecutor who has a minimum amount of evidence that an oligarch’s money has come from a disreputable source can take control of a condo or a yacht and force him into a yearslong legal process.

The Treasury Department has signaled that, going forward, it could require brokers to do due diligence on where property buyers’ money comes from — a change that the Realtors lobby is currently fighting. “Right now, the real-estate industry is required to do nothing,” Delston said. “Everyone from corrupt dictators, to Chinese industrialists, to Russian oligarchs are investing their money in the U.S. through real estate.”

Valuev hopes that his work will point prosecutors and Treasury officials in the right direction. What this means for Gergiev’s Lincoln Center apartment is so far unclear. “It’s just sitting there. He has at times tried to sell it and never pulled the trigger on it,” Sheldon said. “Whether there’s a future depends on what happens to Russian-American relations politically and economically going forward, and the more disastrous the war, the less of a future there is — period.”