This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

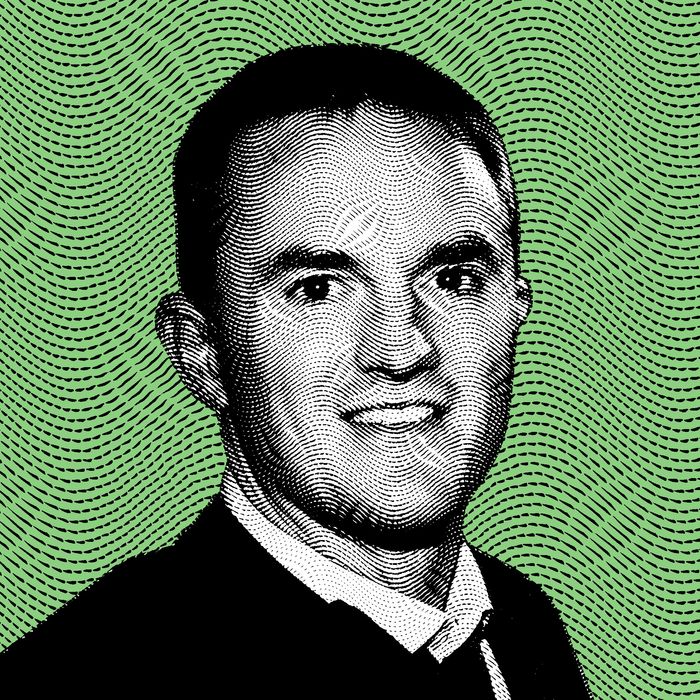

When legendary hedge-fund manager Julian Robertson decided to give Charles Payne “Chase” Coleman III $25 million to start his own fund in 2001, potential investors meeting Coleman for the first time were skeptical.

The 25-year-old analyst, who had worked at Robertson’s storied Tiger Management and was a close friend of his son’s, seemed shy and insecure. “He didn’t look you in the eye,” recalls an investor who says he had to wonder, Was Coleman really talented, or was Robertson’s support just because of the personal connection?

What this investor could not have imagined is that the geeky tech analyst would one day run one of the world’s largest private-investment firms and that he would also become both a central player in a frenzied years-long global tech bubble — one driven by “unicorn” companies trading at absurd valuations — and its bursting over the past six months. The guy who started as a shy analyst would put up impressive gains for years, then suffer mind-boggling losses: $25 billion (and counting) as of June, a record figure even in the lofty world of hedge funds.

The meltdown at Coleman’s firm, named Tiger Global in a nod to his mentor, is one for the ages. “Their losses look to be the biggest in the history of hedge funds,” says one hedge-fund manager, ticking off other notable contenders for that unfortunate title. Tiger Global’s drubbing far surpasses that of Bridgewater Associates, the world’s largest hedge fund, which lost $12 billion in 2020, or Melvin Capital Management, the now-infamous target of the Redditor-led short squeeze of GameStop shares in 2021, which cost it $6.8 billion. Long Term Capital Management, the most notorious hedge-fund blowup of all time, shed a mere $4.6 billion when it almost collapsed in 1998.

Robertson, a Wall Street titan often mentioned in the same breath with fellow hedge-funder George Soros, also has a place on that list of big losses after suffering a tough streak at the end of an otherwise brilliant career. Robertson was defeated by the dot-com mania of the late ’90s — he could never bring himself to buy into the bubble. He shut down Tiger Management in 2000 after losing several billion dollars betting against the hype.

“There is no point in subjecting our investors to risk in a market which I frankly do not understand,” Robertson said in March 2000, as he announced he would return to investors what was left of their money. Robertson throwing in the towel now looks like a perfect indicator of the dot-com madness peaking: He did so in the very month the tech-heavy Nasdaq index set an all-time high that it wouldn’t touch again for more than a decade. When Robertson closed up shop, Coleman and a number of his co-workers decided to leverage Tiger Management’s cachet (and money) and launch their own hedge funds.

Like many of Robertson’s protégés, now known in the industry as Tiger cubs, Coleman was a child of privilege. A true American blue blood, he is a descendent of Peter Stuyvesant, the last Dutch governor of New York. Raised on Long Island’s tony North Shore, Coleman attended the prestigious Deerfield Academy, like his father before him, before going to Williams College. He married well too: His wife, Stephanie Ercklentz, starred in the 2003 documentary Born Rich along with Ivanka Trump.

Whatever initial misgivings early investors may have had about Coleman, over the next two decades, he put up double-digit returns annually and became heralded as a wunderkind. Coleman could not quite match Julian Robertson’s legendary status (which is also derived from some 200 hedge funds that trace their roots back to him), but he built a firm much larger than his mentor’s flagship Tiger Management — and made a lot more money.

At the end of last year, Tiger Global had become one of the biggest firms of its kind — it operates a hedge fund, a long-only fund, and several venture-capital funds — in the world. Including the debt it employed, it was managing about $125 billion with an investment staff of 52 people, according to a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission. (Excluding debt, it had $95 billion.) A year earlier, Tiger Global’s hedge fund had topped a widely followed industry performance list — making some $10.4 billion for investors during the pandemic year of 2020, when its tech bets skyrocketed. By almost any metric, it was one of the most successful players in an extremely crowded and competitive global industry. At the time, Coleman was only 45, the youngest hedge-fund manager to ever make the list. His net worth would soon hit an estimated $10 billion.

The glory days ended over the past six months, though, with the ongoing collapse of high-flying growth stocks — eerily reminiscent of the bursting of the dot-com bubble shortly after Robertson threw up his hands and called it quits.

But what happened to Robertson’s fund and what happened to Coleman’s are almost mirror opposites. Robertson lost money because he refused to invest in the bubble — the old-economy stocks he prized were out of favor, while speculative technology companies soared in value. Coleman has lost money in 2022 because Tiger Global investments were key to making speculative tech stocks go up, and the firm got hurt badly when those same positions started going down. “Tiger Global is the center of the growth bubble,” says a hedge-fund manager who has ties to the Tiger clan. Like many others interviewed for this article, he requested anonymity because he feared repercussions from the firm. Several others call Tiger Global “the poster child” of the tech meltdown, both because of its own role and because its success engendered a lot of imitators. Well-known Tiger investments such as Peloton, Roblox, Uber, Robinhood, Warby Parker, and Carvana have been among the biggest losers in U.S. markets — in some cases down more than 90 percent.

This year, Tiger Global’s hedge fund fell an astonishing 52 percent through May, according to an investor letter – much more than the overall market (down 20 percent) or the tech-heavy Nasdaq (down 33 percent). Its long-only fund has fallen even more — some 60 percent this year. That means Tiger Global has lost about three-quarters of the gains made for investors since launching the hedge fund in 2001, according to calculations from data provided by Rick Sopher, chairman of LCH Investments in London. The total combined losses in the hedge fund and long-only fund based on Sopher’s analysis are about $19.7 billion.

Tiger’s venture-capital funds have lost money too. According to a recent letter to investors, Tiger’s VC funds were off by an average 9 percent for the first quarter — equating to $5 billion more in losses. But write-downs in venture capital typically have a lag effect with the stock market, which means there is likely a lot more pain to come. It’s already happening, with recent reports that valuations of two big unicorns, Stripe and Instacart, have been sliced by 40 percent. Tiger Global is invested in both.

“Venture’s further at the end of the risk spectrum, so if the market keeps going down, that stuff should be marked down more,” says Dan Rasmussen, a former Bain Capital analyst who now runs hedge fund Verdad. He estimates there’s a “50-50 chance” Tiger Global’s venture-capital funds will drop more than the hedge fund.

Should that happen, the total losses would outdo those of fellow Tiger cub Bill Hwang, whose family office Archegos Capital Management lost $35 billion when its implosion roiled the markets last year. Hwang, whose charitable foundation invested in Tiger Global as recently as last year, has since been indicted for fraud. (Tiger Global was not implicated and says it has nothing to do with Hwang, whose hedge fund was shuttered in 2013 to settle earlier insider-trading allegations.)

Based on current numbers alone, Tiger Global’s losses appear to exceed recent ones at its much-larger Japanese rival, Softbank Vision Fund, which drew mainstream attention for pumping billions of dollars into WeWork before the real estate–slash–lifestyle company blew up in a massive scandal in 2019. At the end of March, Softbank Vision had lost $20 billion over the past year.

Although the downturn may force Tiger Global to be more open, historically it has been notoriously secretive. Its partners do not talk to the media, nor do they speak at industry conferences. Some investors, who say they fear reprisals if they talk to reporters, complain that in recent years Coleman had become even more aloof. (Coleman declined to speak to New York, as did Julian Robertson.)

The only known interview Coleman has given was with author Sebastian Mallaby for his new book on venture capital, The Power Law. In it, Coleman told Mallaby that when he launched Tiger Global, he felt daunted by the idea of hiring investment professionals older than him.

In Tiger Global’s early days, its employees dressed in formal business attire “in the hopes that investors and companies might see past our limited experience and take us seriously,” the firm wrote in a 2020 letter to investors commemorating its 20th anniversary.

The young hedge-fund manager’s key hire turned out to be Scott Shleifer, who had spent the prior three years at the Blackstone Group, the heavyweight private-equity firm. The two men had opposite temperaments — Shleifer is hard-charging and outgoing — and came from different worlds. As Shleifer explained to Mallaby, “My father sold couches for a living.”

Shleifer’s strategic vision for Tiger Global was rooted in an aggressive approach — one that he also embodied in his private real-estate dealings: Last year, he spent $122.7 million for Donald Trump’s former Palm Beach estate after looking at the house for 15 minutes, according to the New York Post. It was the highest price ever paid for a home in Florida. In true Tiger Global tradition, the transaction was completed in record time.

Tiger Global’s move into venture capital, led by Shleifer, started in China in the firm’s early years before coming to include U.S. companies. It focused on revenue growth as the key metric (versus, say, profits) and would become a template many other VC firms soon followed. (Tiger Global famously backed Facebook and LinkedIn, two early winners.)

Silicon Valley insiders often bemoan the idea that Tiger Global threw money at tech start-ups with a size and velocity that changed the industry for the worse. “Balls to the walls” is how one of its investors described the firm’s approach. In recent years, Tiger Global seemed increasingly to dominate the VC world. In 2021, it backed a dizzying 335 deals, more than one investment per business day. “Tiger Global took the crown as 2021’s top investor,” venture-market-intelligence firm CB Insights wrote, meaning that Tiger Global made the most investments during that year.

“Tiger could be a little bit more aggressive. They could move quicker. They paid higher prices than a lot of their venture peers,” says hedge-fund consultant Greg Dowling of Fund Evaluation Group. “And that worked really well until everybody else started following the same strategy. They got bigger, which means you had to put more money out. Prices got higher. And so at some point, it stopped working.”

Tiger Global had created a symbiotic relationship between its hedge-fund holdings and its venture-capital investments. As a venture firm, it invested in private companies — mostly internet, consumer apps, or software — as they were getting closer to going public. With its aggressive style, Tiger helped drive up valuations overall for such companies, boosting the rise of the so-called unicorns — privately owned start-ups worth more than $1 billion. (There are now 1,338 of them valued at $4.6 trillion, according to CrunchBase; Tiger Global has made 351 investments in them.)

Based in New York City, Tiger Global was never part of the Silicon Valley culture of seeking out visionary founders and holding the hands of entrepreneurs. It differentiated itself by coming in to later rounds of financing and plugging numbers into its models — arguably bringing more of a Wall Street ethos than a Sand Hill Road one to venture investing.

The hedge-fund portion of the strategy came into play as these unicorns went public: Before the IPOs, Tiger Global’s hedge fund would also invest in the same unicorns as were backed by its VC funds. In a buoyant market, the stocks typically took off, as fellow Tiger cubs as well as other hedge funds bought into what became a growth-stock bubble. That way, a big winner in the venture-capital portfolio could become a big winner in the hedge-fund portfolio. “Everybody used to copy them,” says the fund manager with ties to the Tigers. “That’s why everybody’s in the trades with them. That’s why everyone started doing dumb shit, like buying stocks at 30 times sales.” (For example, a company with $100 million in revenue would be valued at $3 billion at a 30-times sales ratio. Although such valuations became common in the past few years, by historical measures they are ridiculously rich.)

“Ask 10 VCs for their thoughts on Tiger et al., and most of them will react with a mix of dismissiveness and disgust. They’ll say that crossovers” — that is, hedge funds that got into venture capital — “are drastically overpricing rounds, not doing enough diligence on their investments, or are in some other way breaking the spoken & unspoken ‘rules’ of venture,” Everett Randle, a partner at San Francisco–based venture capital firm Founders Fund, wrote on his blog last year in the midst of Tiger’s most aggressive financing spree.

“Tiger is eating VC,” he concluded. Randle heralded Tiger Global’s approach as one that would “fundamentally change the way that venture capital is raised” and said that “Tiger has developed a flywheel that enables them to offer better/faster/cheaper product to founders while generating more $ gains than their competitors.”

One of those unspoken “rules” Tiger Global broke was allowing separate Tiger Global venture-capital funds to invest in the same company. This practice had often been prohibited in VC-land in the past because the newer funds can end up making the older funds look better simply by buying a piece of the companies in the earlier funds’ portfolio. “In most cases, you’re not allowed to do this,” says Michael Ewens, a finance professor at the California Institute of Technology who studies entrepreneurship, referring to provisions in contracts between VC fund managers and their investors.

Tiger Global takes issue with these criticisms. It bristles at the widespread notion that the firm does little due diligence, saying it outsources some of its research to consultants like Bain. And while it has led more deals than many other players, the firm points to CrunchBase data showing its average investment of $42 million over time is far smaller than that of SoftBank, which comes in at an average of $360 million. Finally, Tiger Global says two or more of its funds may invest in the same company if the firm thinks it’s a good investment.

There is little doubt, however, that Tiger Global wanted to do a lot of deals as quickly as possible. In its 2020 anniversary letter, the firm said it was “searching for ways to make our investment flywheel spin faster.” Now it seems to have spun out of control.

Most of Tiger Global’s stupendous growth came in the past two years. Since the end of 2019 until the end of 2021, the firm’s assets tripled, according to its annual filings with the SEC. Following its blowout year of 2020, Tiger Global raised its largest VC funds ever, collecting $6.7 billion from institutional investors like endowments, pension funds, sovereign-wealth funds, and individual members of the global elite desperate to get a piece of the action. Since then, it has raised yet another blockbuster fund, landing $12.7 billion, according to Pitchbook. All told, Tiger has raised 14 venture funds, and industry observers worry that some of the more recent ones will face the biggest losses. (For example, it’s an investor in several private crypto-infrastructure companies as well as publicly traded Coinbase.)

But in the early days of the pandemic, when money flooded the markets, crypto and consumer-oriented tech stocks soared during the work-from-home craze, including many financed by Tiger Global. The reversal in a world of higher interest rates and rising inflation has been ugly.

Many of the stocks that Tiger Global owns have simply been obliterated in the new environment. Peloton is one of the most dramatic examples. Tiger Global was one of the biggest VC backers of the home-biking system, owning 20 percent of the shares when it went public in 2019. At one point, Tiger’s stake was worth $6.5 billion, based on a relatively modest investment. Meanwhile, the stock has been tanking — it is now almost 95 percent off its highs and trades at around one times sales, compared with 20 times sales last year.

Recent crash aside, Tiger Global definitely profited from its Peloton investment (and has been cashing out); but the bigger question is whether the firm’s larger model still works. “The issue is that a lot of these companies existed to grow the revenues and ignore profitability,” says Harris Kupperman, the founder of hedge fund Praetorian Capital, who argues that these companies enriched the owners and early investors and left later investors with massive losses. “They always said that they’d grow to a scale that they’re profitable, but if you look at something like Peloton, there was a period of 18 months when everyone was at home and the gyms were closed because of COVID. And they sold a lot of these bikes, but they still couldn’t make money at it.”

“You had companies that were losing hundreds of millions of dollars a year, and the stock price went up, so people said, ‘Okay, profits don’t matter anymore,’” he says. “But in the end, profits matter.”

If that thinking holds, the financial world may be returning to the value-investing approach that Julian Robertson was known for decades ago. People like Kupperman are even using the term “old economy” to refer to today’s stock-market winners, just as they did in the 1990s, while invoking the “new economy” term to talk about today’s beleaguered growth stocks.

The so-called new economy stocks hardest hit in today’s markets have been those Kupperman has christened “the Tiger 40” — the 40 top stock holdings Tiger Global disclosed at the end of 2021 — and which short sellers say they are targeting.

“The Tiger-40 is a list of the most over-owned hedge fund hotels I can think of,” Kupperman wrote on his blog, Adventures in Capitalism, in January. (“Hedge fund hotel” is industry slang for an investment that’s very popular among hedgies.) “Most of the large portfolio managers all know each other. They share the same notes. They copy each other and they copy what’s been working.” Indeed, a number of other Tiger cubs show up in these crowded trades — names including Coatue Management, Lone Pine Capital, Maverick Capital, Viking Global Investors, and D1 Capital Partners. (These hedge-fund firms have also followed Tiger Global into investing in venture capital. All are facing significant losses this year.)

As the Tiger 40 stocks have tanked, the hedge funds that own them have gotten margin calls asking for more cash or collateral for their loans and redemption notices from investors wanting their money back. That in turn created more selling, which created even more selling, and so on. The same feedback loops that were operative on the way up are working in reverse on the way down.

Bloomberg recently highlighted 13 of the worst-performing stocks held in common among these funds. The more familiar names are former high-fliers Carvana, Netflix, Shopify, and electric-vehicle start-up Rivian. All have fallen more than 70 percent, and Tiger Global was in all of them.

While those names are well known to many American consumers, less familiar are the Chinese tech companies in Tiger Global’s portfolio. Last year, Tiger Global owned more stakes in U.S.-listed Chinese stocks than any other hedge fund, according to a Bloomberg analysis. These now face a double threat. Not only has the Chinese government cracked down on them (a process that began with Jack Ma’s Alibaba), the SEC is also threatening to delist many of these stocks because China won’t allow foreigners access to its companies’ financial audits as a recent U.S. law requires. JD.com, one of Tiger Global’s largest and most successful holdings for years, is one of the companies on the SEC’s target list for delisting.

Tiger Global may not realize that, as financial historian Jamie Catherwood puts it, “the party’s over.” But that’s apparently a classic response. When any bubble bursts, says Catherwood, “there is always a hesitance to admit that mistakes were made.”

For Tiger Global, whose strategy seems innately tied to the tech bubble, what can they say?

“We believe in innovation and technology,” the firm wrote to its investors at the end of the first quarter, defending its approach in investing. Although the firm admitted that it should have taken more chips off the table, it also seemed ready to hold steady, saying “typically when we face this kind of downdraft we more than make it up” when stocks recover.

Since then, of course, holding on has caused its losses to deepen. In May, Tiger sent a quick communique to investors in its hedge fund, promising them that it was “committed to earning back our losses,” though people familiar with the fund say they know that it will be a long, hard road back to break-even. Although Tiger Global has since tried to assure investors that its business is “set up to weather storms when they arise,” the reality is that few hedge funds have survived such a steep drawdown.

By June, the mounting red ink led Tiger Global to cut its management fees and take the unusual step of telling investors in its hedge fund that if they wanted to get their money back, the fund would temporarily alter the contractual terms to raise slightly the limits on withdrawals. But there is one problem with that offer — and it reflects the downside of the hybrid private-public approach that Tiger Global popularized in recent years: As Tiger Global’s publicly traded stocks have been vaporized, much of the remaining value in the hedge fund is in the private companies it holds, and those stakes can’t be easily sold. So investors who want out won’t be able to get the private-company portion of their investment. Instead, it will be set aside in hopes that someday those holdings will be worth selling. Meanwhile, Tiger Global’s venture-fund investors will have a longer wait — those funds have a ten-year lockup.

Looking back, Rasmussen, the former Bain Capital analyst and current hedge-fund manager, believes that it’s easy to see how Tiger Global got into its current predicament. “They’ve just been winning, and winning, and winning,” he says. “I think one thing that happens to people who win, win, win, win, is they get overconfident, and they can’t imagine a scenario where they’re not winning.”