This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On August 28, 2021, Rita Chatterton, a sandy-haired 64-year-old woman, stood at a podium in Albany to receive a “Trailblazer Award” from the International Professional Wrestling Hall of Fame. The Hall of Fame was the brainchild of a wrestling fan named Seth Turner, who wanted to honor Chatterton for being the World Wrestling Federation’s first female referee. “Seth calls me and says, ‘Rita, I need you to do the Hall of Fame with me,’” Chatterton recalls. At first she refused; she didn’t want to revisit her time with the WWF, now known as WWE. But Turner finally convinced her, and she was ultimately glad she did it. “I always said I don’t want to live and die and be forgotten,” she told him.

Chatterton has been forgotten before. In 1992, she came forward publicly to accuse Vincent Kennedy McMahon, the iron-willed owner of the WWF, of raping her in the summer of 1986. However, the statute of limitations for rape had already run out by then, so no charges were brought against McMahon. What’s more, the accusation came out while the WWF was mired in a number of unrelated scandals, and it got lost in the shuffle.

Since then, her story was whispered about and occasionally cited by wrestling journalists bold enough to risk earning McMahon’s ire. But such occasions have been rare. The reporters’ reticence had been understandable, and not just because they fear McMahon. The bigger problem has been that no one would come forward to speak on the record.

That’s starting to change. In June, The Wall Street Journal reported that McMahon had paid millions of dollars of his own cash to silence women he had sexual relationships with while they worked for him. In the wake of the report, McMahon stepped down as chairman and CEO of the company, letting his daughter, Stephanie, replace him in the interim — although it’s unclear how much power he has actually ceded.

The news so disgusted Leonard Inzitari, a former professional wrestler, that, in a conversation with me, he did something no wrestler ever has: corroborated the allegation that McMahon raped Chatterton. “I remember it like it was yesterday,” says Inzitari. “She was a wreck. She was shaking. She was crying.”

Inzitari’s in-ring alias was “Mario Mancini,” and he was what the wrestling industry calls a “jobber”: He’d be paid a few hundred bucks per show to “lose” to more famous wrestlers in their choreographed matches. Inzitari, like everyone else involved in the WWF, obeyed the whims of McMahon, who began to take control over his father’s company in 1982. In the three decades since Inzitari retired, he has always taken care to speak highly of McMahon in interviews.

But now, as Inzitari puts it, “He’s dug himself such a deep hole that I’m just tired of it. I can’t do it anymore.”

According to Inzitari, in that summer of 1986, he found Chatterton standing alone near the wrestling ring a few hours before a WWF show. “She looks at me and bursts out in tears,” Inzitari recalls. “And she grabbed me, and I go, ‘Rita, what happened?’”

Chatterton began to reply: “I was in Vince’s limo …”

Before she could continue, Inzitari let out an involuntary, “Oh, no.”

“Lenny, he took his penis out,” he said Chatterton told him between sobs. “He kinda forced my head down there, and I made it known I wasn’t interested in doing that.”

Inzitari was not surprised. He had “heard a lot of different stories” about McMahon’s sexual proclivities. “He was strange, brother.” (McMahon did not respond to a request for comment made through WWE and his personal lawyer, Jerry McDevitt.)

Inzitari asked Chatterton what happened next.

“Then, [Vince] pulled me on top of him,” she told her friend. According to her, she was wearing jeans that McMahon forcibly took off. Soon, as Inzitari puts it, “He was inside her.”

“You’re done,” Inzitari remembers telling Chatterton. “Your time’s numbered. You’re not gonna be here.”

Sure enough, he was right: The WWF stopped calling Chatterton for referee appearances, starting that summer.

Inzitari doesn’t use the word rape while talking about what happened. But he describes something that sounds like the conventional definition of that term.

“Was she taken advantage of? Absolutely,” Inzitari says. “Was she scared to death? Absolutely. Did she wanna do that? Probably not.”

Inzitari said nothing to anyone about what Chatterton told him. “You just keep your mouth shut, because it’s Vince McMahon,” Inzitari says. “What are you gonna do, stooge on Vince McMahon? You’re gonna be blackballed from the wrestling business!”

Chatterton disappeared from the public eye immediately after she made her accusation against McMahon on Geraldo Rivera’s television show in 1992. She has given no interviews about the alleged incident, nor about the trailblazing life and career that it disrupted. Chatterton has been silent — until now.

“Every Sunday, most people went to church,” Chatterton tells me. “My family, we watched wrestling.”

Born Rita Filicoski in Albany on January 22, 1957, she was raised in the nearby town of Mechanicville. She had a brother, Christopher, four years younger than her, who was the biggest wrestling fan in the house. “From the time he was a little boy, it’s all he talked about: ‘I’m gonna be a wrestler,’” Chatterton recalls.

The wrestling they watched was produced by McMahon’s father. In the ’70s, Vince was merely an announcer for his dad’s programming. The Filicoskis would watch the tall, broad-chested man on the screen interview wrestlers and do play-by-play commentary.

Rita’s little brother never got to become a wrestler. Christopher died in a car accident on May 3, 1979.

“The day he was killed, I went into his room,” Chatterton says. “He had a notepad there. He had all the wrestling schools listed: how much it was gonna cost, how he’d pay for it.” She realized he had his dream all mapped out.

“So,” she says, “I decided to go into wrestling for him.”

At the time, Chatterton was 22 years old, divorced, raising a daughter on her own, and working as a delivery driver for Wonder Bread in the Albany area. But before she could start training, she developed a cyst that caused one of her lungs to collapse. She had to go through major surgery and assumed that was the end of her ring dreams.

Her father came to visit her in recovery at the hospital. Wrestling happened to be on the TV in the room. “All of a sudden, this lightbulb went on,” Chatterton recalls. “I said to my dad, ‘I can’t be a wrestler, but I can be a referee.’ I’d still be honoring my brother, but wouldn’t get beat up the way the wrestlers do.”

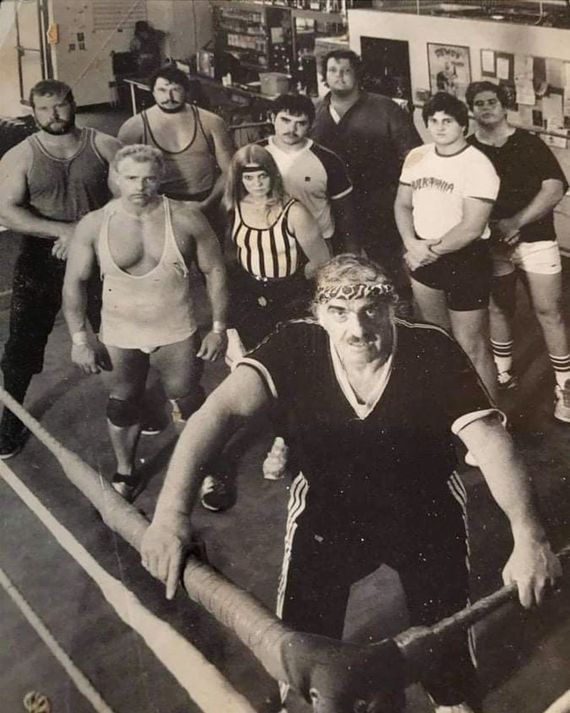

The role of the referee in pro wrestling has always been strange. Wrestling was still masquerading as a legitimate athletic competition back in the ’80s, so every match had to have a referee who would move around the ring and pretend to enforce the largely arbitrary “rules”: no closed-fist punches, no interference from a wrestler’s allies, no leaving the ring for more than a count of ten, and so on. In New York, pro-wrestling referees even had to be licensed by the state’s athletic commission.

Referees are still a key part of the action today, often engaging in narrative business that involves them being “distracted” or even ostensibly knocked unconscious. At the end of a match, if a wrestler pins their rival for three counts, it is the referee who slaps the ring canvas three times to mark that person as the “winner.”

Female referees were unheard of.

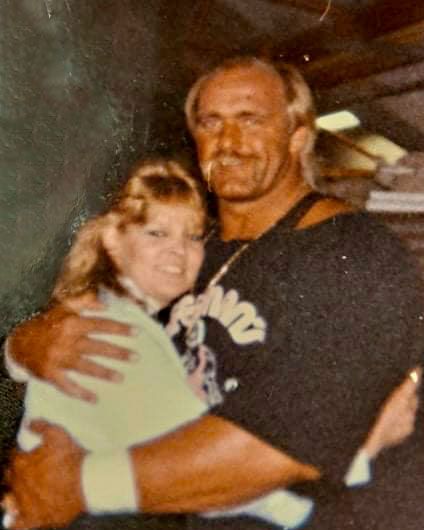

After a long recovery from the collapsed lung, Chatterton ended up training at a wrestling school from her brother’s list, Passariello’s Quest, in southwestern Connecticut. Her trainer, Tony Altomare, was initially reluctant to teach a woman. She was slight and graceful, putting her long hair into a ponytail when she stepped into the ring. It was at Passariello’s Quest that Chatterton met Inzitari, who was training to be a wrestler. The two became fast friends. He chose the ring name “Mario Mancini”; she chose “Rita Marie.”

In 1984, Chatterton completed her training and received a license to referee in New York. Her first match was a WWF show at Orange County Fairgrounds in Middletown. She did some more gigs for the WWF, then caught a break when she got in touch with McMahon adviser George Scott around the end of the year. The day after she spoke to Scott, her phone rang.

“Rita?” the voice on the other line said. “Vince McMahon here.”

At the time, McMahon was enacting an aggressive expansion program, attempting to destroy the dozens of regional wrestling promotions that existed around the country. As part of his blitz, he had launched a storyline involving Cyndi Lauper: The pop star was made the “manager” of a wrestler named Wendi Richter, and the two of them stood up for women’s rights against a rival’s misogyny. He naturally was interested in highlighting his company’s first female referee.

McMahon said he’d heard good things about her. “I’d like you on television soon,” he said. “How about Saturday night? Can you make it to Madison Square Garden?”

“It was insane,” she recalls. “I’m used to doing little 3-, 4,000-people venues. Nothing compared to MSG.”

“I’ll be there,” she told McMahon.

After making her TV debut in that match at MSG in January of 1985, McMahon called Chatterton again. “He said he was impressed with what I did, impressed with my work, and wanted me to go full-time,” she says. “He promised me half a million dollars a year. At the time, I knew that’s a huge amount of money, but I didn’t know what the wrestlers were making.” She figured their fees must have been in that range, and that she could get there, too. In reality, while major stars like Hulk Hogan reportedly made up to $10 million a year, salaries for wrestlers even now average around $51,000 — and all (including Hogan) were independent contractors, not employees.

McMahon also had a warning. “Keep yourself clean,” he said, in Chatterton’s telling. “I don’t wanna see you messing around with any of the wrestlers. You keep it professional.”

Inzitari remembers her coming to him after McMahon had spoken with her.

“I’m gonna be on the cover of Women’s Day and Better Homes and Gardens and Time magazine,” Chatterton said.

“Who’s telling you that?” he replied.

She said it was McMahon.

Inzitari immediately suspected something might go awry. He’d already heard plenty of rumors about McMahon. “I go, ‘Oh, Rita, please — if you do anything with him, you’re gonna be gone,’” Inzitari tells me. “I told her, ‘Stay. Away. From. Vince.’”

McMahon kept putting her on televised matches, and the WWF arranged for her to be briefly mentioned in a Cosmopolitan spread. It all gave her hope that a full-time position was around the corner.

Her boss at Frito-Lay (she’d left Wonder Bread, but was still a delivery driver) eventually gave her an ultimatum: Either she could keep her steady job as a driver or she could commit to wrestling.

“I talked to McMahon,” Chatterton recalls, “and he said I had a half-million-dollar contract coming my way anyway … I was pretty confident it would happen. So I left Frito-Lay.”

“That was one of those jobs with a 401(k),” Inzitari recalls. “You could retire after putting in your years at Frito-Lay. But she dumped it all because Vince said she’d be on the cover of Time.”

She never was. But she did appear in the WWF’s in-house magazine, and she made an appearance on the company’s forgotten, McMahon-hosted cable talk show, Tuesday Night Titans. She wore a loose white dress and, as she sat across the desk from a tweed-jacketed McMahon, the boss gassed her up.

“You have been accomplishing things that, certainly, women have never accomplished before,” he said with a smile. “I mean, you weigh approximately 120 to 130 pounds — not getting personal, somewhere in there. And for you to step into the ring with the giants, I mean, you realize what can happen to you, do you not?”

In Chatterton’s telling, she traveled to Poughkeepsie’s Mid-Hudson Civic Center, where the WWF regularly held tapings of its televised matches, in July of 1986. (Though she says she doesn’t remember the specific date, she said on Geraldo’s show it was on July 15.) She wanted to get an audience with McMahon and talk about her future with the company. She says she found him in a hallway, and he told her they should talk after the show, at a nearby diner. So she drove to the diner and found McMahon there — along with about a dozen other people.

“We’re sitting at this big round table,” Chatterton tells me. She brought up her career. “Vince McMahon put his finger to his mouth, in a shhh sign.”

She got up and used the bathroom. “When I come out of the ladies’ room, McMahon’s standing there,” she recalls, “and he says, ‘I don’t wanna talk to you about your career in front of all these people, because it’s none of their business.’” She thought that sounded reasonable. He suggested they go to another diner down the street, just the two of them.

They left the building, McMahon got into his limousine, and Chatterton was getting into her car when he rolled down his window.

As Chatterton puts it, McMahon said, “I’m tired, let’s talk here,” referring to his limo. “It’ll only take ten minutes.” McMahon’s chauffeur, Jim Stuart, left the limo and went into the diner. According to Chatterton, she and McMahon were alone in the vehicle.

She declines to describe to me the specifics of what happened next. But when she came forward in 1992, she gave a detailed account before a live studio audience. Chatterton sat down for interviews on two programs hosted by Rivera: a newsmagazine called Now It Can Be Told and a daytime talk show called The Geraldo Rivera Show.

“He starts talking about a half-a-million-dollar-a-year contract,” she told the crowd at the latter program. “Next thing I know, Vince McMahon is unzipping his pants.”

“Vince continued to, you know, ‘If you want a half-a-million-dollar contract, you’re going to have to satisfy me, and this is the way things have to go,’” she continued. “Vince grabbed my hand, kept trying to put my hand on him. I was scared. At the end, my wrist was all purple, black, and blue. Things just didn’t … He just … God, he just didn’t stop. This man just didn’t stop.”

According to Chatterton on the show, Vince said, “How’s your daughter going to go to college? Of course, she doesn’t have to go to college.”

As Chatterton put it then:

I was forced into oral sex with Vince McMahon. When I couldn’t complete his desires, he got really angry, started ripping off my jeans, pulled me on top of him, and told me again that, if I wanted a half-a-million-dollar-a-year contract, that I had to satisfy him. He could make me or break me, and if I didn’t satisfy him, I was black-balled, that was it, I was done.

“One of the things that sticks with me, and always will,” she tells me, “was, after he got done doing his business, he looked at me and said, ‘Remember when I told you not to mess with any of the wrestlers? Well, you just did.’”

Chatterton says she “went to the ladies’ room of the diner and cried my heart out.” After that, “I washed up, got in the car, went home, and took a five-hour shower.”

The next day, she says, she called a lawyer whose ads she’d seen on local television. “He was willing to take the case, but he knew it would be an uphill battle,” she says. “It came down that it was my word against McMahon’s, because I took a shower and didn’t go to the hospital.”

“I was scared,” she continues. “He was powerful. It was gonna be him over me.” She decided not to press charges.

Chatterton says she only really had two friends in the WWF: Inzitari and the late André Roussimoff, the world-famous wrestler known as Andre the Giant. She says she told both of them what allegedly happened “within a couple weeks of it happening.”

Chatterton remained a licensed wrestling referee, and although the WWF stopped asking for her, she says the New York athletic commission had her work a small handful of untelevised WWF matches in the years after 1986. She says she always turned down assignments for televised shows, because she knew McMahon attended those. Chatterton kept a low profile. She says she often considered coming forward with a legal case, but didn’t want to put her parents through the storm that might ensue. “My mom was 80 pounds soaking wet, my dad had already had two heart attacks,” she says. “They couldn’t handle that pressure.”

Chatterton’s mother died in 1991 and her father died in 1992. Her restraints were gone. “I wanted to tell the world what a scumbag McMahon was,” she says.

Within about a month of her dad’s death, she appeared on Geraldo’s shows after they approached her. When I ask how Rivera and his producers found out about her story, she says, “I have no idea.” (I was unable to reach Rivera or his producers despite requests for comment. However, Inzitari says there had been whispers among wrestlers that Chatterton had slept with McMahon, and they may have found their way to someone on Rivera’s team.)

After Chatterton laid out her allegations in brutal detail, the WWF repeatedly declined to comment. The wrestling firm was embroiled in at least three other major scandals at the time — including allegations of child molestation, sexual harassment, and steroid distribution — and Chatterton’s story failed to make many waves.

“Everything was pretty quiet immediately after,” she tells me. Chatterton even worked a few more Vince-free WWF matches — though she always made sure she “did what I needed to do and left.” Her primary source of income was bartending.

She finally decided to give up on wrestling when Andre the Giant died in early 1993. She and Roussimoff had remained close, and she attended a memorial service at Roussimoff’s estate in rural North Carolina on February 24, 1993.

McMahon was also in attendance.

“Vince walked up to me,” Chatterton recalls, “and said, ‘It’s nice to meet you.’”

“He knew exactly who I was,” she adds. “I said, ‘Nice to meet me?’ I told him to go fuck himself and walked away.”

It was their final face-to-face interaction.

Nine days later, McMahon and his wife, Linda, filed a lawsuit against Chatterton, Rivera, Rivera’s producer, two of Rivera’s production partners, and disgruntled former WWF wrestler David Shults. The suit claimed Chatterton had been part of a conspiracy involving all of the defendants, in which they “performed numerous tortious acts with the intent of inflicting severe emotional distress upon Plaintiffs, including the fabrication of a false accusation of rape against Plaintiff Vincent McMahon which was aired on the nation’s airwaves.”

The suit further claimed that Chatterton “was not a competent ring referee and posed a danger to herself in the ring,” which was why they had ceased to feature her. It said Shults was the hidden figure behind her pulling the strings: “Shults contacted Chatterton in order to induce her to make a false claim that McMahon raped her while she was still affiliated with the WWF,” the suit read. “Chatterton agreed with Shults to falsely accuse McMahon of raping her in 1986 in order that such charges could be made for the first time in the context of the filming and production of the Now It Can Be Told program.”

The suit never went anywhere: Filings were made by both sides, but the McMahons abandoned the effort when it became clear Vince would have to go to trial on the steroid-distribution charges in which he was later acquitted. He had enough on his plate, and the suit was discontinued without resolution.

That was it for Rita’s time in the public record for a very long time. She trained to be a youth counselor and worked in that field for many years, only retiring in 2018 when she sustained nerve damage after slipping on some ice. In those decades, she stayed as far away from wrestling as she could.

“I wanted nothing to do with it,” she says. “It was a whole other lifetime. Something I used to do. Over with. Done.”

Memory of Chatterton’s claims has all but vanished from the mainstream media. When the political website Talking Points Memo brought up the allegation in the context of Linda’s 2010 run for Senate in Connecticut, the McMahons’ longtime lawyer, Jerry McDevitt, brought the hammer down.

“Make no mistake,” McDevitt told the TPM reporter when she asked for comment, “if those false allegations are repeated now and again, Mr. McMahon will pursue all available remedies against those associated with this smear job.” TPM ran the post, but didn’t pursue the story further.

Now, with McMahon facing renewed scrutiny for alleged sexual misconduct, Chatterton is cautiously hopeful that the man might face consequences.

“He’s not gonna pay for what he did to me,” she says. But she’s glad the hush-money allegations are coming to light. “Now this girl’s come forward,” Chatterton says of the paralegal whose friend sent the initial emails to the WWE board, “and I’m sure others will come forward. Because we’re not the only two. There’s not a doubt in my mind about that.”

Chatterton pauses and thinks for a second. She chuckles a little.

“As far as wrestling goes, I guess I’m the first in a lot of things,” she says. “As far as I know, I’m the first to come out with the whole issue of what a scumbag he is.”

Inzitari, too, sees storm clouds ahead for his onetime employer.

“I’ll tell you why I’m hopping on the bandwagon now,” the former grappler tells me. “There’s worse stuff than that.”

Abraham Riesman is the author of Ringmaster: Vince McMahon and the Unmaking of America, which will be published by Simon & Schuster in March 2023.