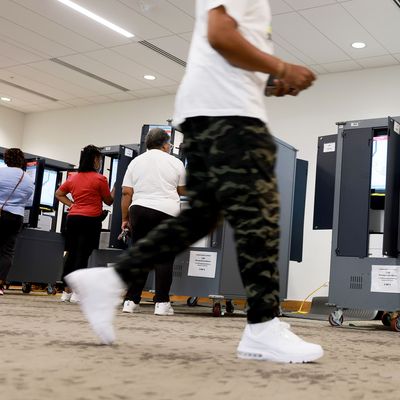

Last month, there was a lot of excitement about high voter turnout in Georgia’s primary. In the marquee gubernatorial races, 1.9 million voters turned out as opposed to 1.2 million in 2018. That raised eyebrows since the state’s Republican-controlled legislature famously enacted a new voting and election law in 2021 that was aimed at cracking down on the allegedly loose voting rules that prevailed during the pandemic election year of 2020. Plus, while Georgia sent absentee-ballot applications to all registered voters as an emergency measure in 2020, this year the policy reverted to absentee voting only being available by request.

So with tighter and more complicated voting-by-mail and voter-ID provisions, and potential state intervention in allegedly lax county election-board proceedings, it definitely got harder to vote in Georgia this year. Yet turnout went up, at least in the primary.

Now on the other coast, California is seeing the opposite situation. Turnout is almost certain to be depressed in Tuesday’s primary, as the Los Angeles Times reports, though voting is far easier in the Golden State:

Early turnout has been dismal before all polling sites opened Tuesday, election day, across California. Every registered voter in the state was mailed a ballot, but only 15% had gotten them to election officials or weighed in at early in-person vote centers by Monday night, according to election data reviewed by the consulting firm Political Data Intelligence.

… California’s early returns are a major drop off from the same period in September’s gubernatorial recall election, when nearly 38% of voters had voted as of election eve. Some 22% of voters had cast ballots at the same point before the last midterm primary election, in 2018, when ballots were not mailed to all California voters.

The comparison with 2018 is, indeed, striking because California now sends mail ballots (with prepaid reply envelopes) to all registered voters. But the drop from 2021 is also dramatic, since normally single-contest recall elections draw far fewer voters than regular primaries and general elections.

What’s going on in these two states? The most obvious thing is that Georgia had some red-hot contests on the Republican side of the ledger, with vast spending all around. And the boost to turnout also extended to Democrats who were allowed to cross over into the Republican primary, and did so in sizable numbers either to smite Trump’s endorsee or to choose weak opponents.

Meanwhile, California’s 2022 primary has no marquee race: Democratic governor Gavin Newsom and Senator Alex Padilla face no serious opposition. And, perhaps more importantly, the Golden State’s top-two system may discourage turnout by denying primary voters any real consequences: In state elections, candidates from every party (or no party) compete on crowded ballots, with the top-two finishers proceeding to the general election regardless of their shares of the vote. In many contests, both the parties and the candidates pretty much know who will appear on the general-election ballot, and hold their powder (and their spending) for the stretch drive near November. Many voters tune out until November, as well.

California Republicans may have an even stronger reason to give the midterms a pass after all the energy they expended in the ultimately disastrous effort to recall Newsom in 2021. Republicans trying to make the top two must be worried. 2022 should be a year of great enthusiasm for Republicans in California, as it is everywhere else, and usually they turn out more for the primary than Democrats. But this year could be different.

So the differences between the political environment and the primary systems in Georgia and California matter more than simple voting rules in determining levels of turnout. But this does not mean that Georgia’s new restrictions were benign. As FiveThirtyEight’s Alex Samuels explains, it’s possible that turnout would have been even higher in Georgia without the new restrictions, but voters overcame the new hurdles:

Research has found that strict voting laws can backfire and make people more determined to cast a ballot despite the hurdles set in front of them. Consider what happened in North Dakota in 2018. That year, Native American tribal leaders and field organizers concerned about turnout following the passage of a stringent voter ID law responded by rushing to print new tribal IDs. As a result, during that year’s fall midterm, Native American counties recorded historic turnout numbers. Some reporting suggests that Georgia Democrats carried out a similarly energized ground game.

While many vote-suppressing Republicans argue that voting restrictions don’t really dampen turnout, and thus are no big deal, it should never be forgotten that voting rights are rights, and their denial is a matter of injustice, not just inconvenience.

More on the midterms

- J.D. Vance Explains His Conversion to MAGA

- Are Democrats the Party of Low-Turnout Elections Now?

- New Midterms Data Reveals Good News for Democrats in 2024