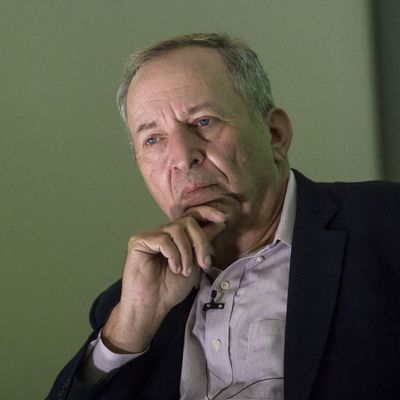

Former Treasury secretary and Harvard University president Larry Summers was right to be pessimistic. The economist, long a prominent but polarizing figure, loudly warned that Democrats’ 2021 stimulus package would lead to high inflation. Summers’s prescience — and correct view that the phenomenon would persist — has positioned him as perhaps America’s most in-demand economic prognosticator. I spoke with him about the latest inflation data, how bad a recession could get, and why so many experts failed to read the monetary warning signs last year.

There seemed to be little good news in Wednesday’s inflation report, with the consumer price index coming in at a 41-year high of 9.1 percent. What was your initial reaction to these numbers?

These were discouraging numbers. Nobody can suppose that inflation is under control when three-month core inflation exceeds six-month core inflation and six-month core inflation exceeds 12-month core inflation. Inflation in today’s report is pervasive and particularly pronounced in persistent components like housing and medical care. Team Transitory was extremely selective last year in failing to recognize housing and medical-care inflation.

President Biden called the new numbers out of date, noting that gas prices have been falling steadily for most of the last month. Others have pointed to data showing that demand in some sectors, like apartment rentals and home sales, may have peaked. But we’ve been hearing this refrain that the worst is behind us for many months. Do you think there’s any validity to it this time?

One of these months it will turn out to have peaked, but core inflation is now running more than three times as rapidly as its target level, and that entirely excludes energy and food commodities. Inflation will come down at some point, but it is unlikely to be a soft landing without economic pain.

You said on Wednesday that we’re not getting out of this without 6 percent unemployment. But many think that even if there is a recession, it could be a mild one. Do you think people are underestimating the possibility of something more severe?

I don’t think there’s any reason to expect a recession of the magnitude that we had after COVID struck or with the financial crisis of 2008. I think the recessions of 1990–1991 and 2001 are better models. But if inflation is to be contained, unemployment is likely to rise to somewhere in the vicinity of 6 percent or more. That would be my uncertain best guess.

The Fed is set to raise interest rates another 0.75 points this month. They’re clearly taking the issue seriously, which they weren’t for some time. Is there anything more that they or Democratic leaders can do at this point?

It is good that, very belatedly, the Fed is moving aggressively with respect to inflation. It would be helpful if they could forecast in a credible way. Their forecast that inflation can be brought down to target levels without unemployment rising above 4.1 percent seems to be extremely implausible. That none of the 19 members of the FOMC expect unemployment at any point to exceed 4.5 percent suggests to me a dangerous level of groupthink.

I’m surprised that thinking is so widespread in the Fed even now, after having been quite incorrect about the shape the inflation wave was going to take. You’d think they’d factor in a little more pessimism going forward.

In fairness, the last forecast was not issued yesterday, and we’ll see how they adjust. [Editor’s note: It came out in mid-June.] But it is central in policy to see the world as it is, not as you would like it to be. And I think the Fed has been guilty of substantial and continuing wishful thinking.

You were probably the most prominent voice warning that last year’s stimulus package would lead to higher inflation. To what extent do you think we’re still dealing with the fallout from that? Inflation is a huge problem in Europe and elsewhere, too. If no stimulus package existed, would the macro environment now be that much better?

I think excess fiscal and monetary stimulus is a substantial contributor to our inflation problem. Of course, there were supply shocks, but when the economy’s capacity is limited, it’s desirable to limit demand to that capacity rather than overstimulate the economy. Moreover, in many of the bottleneck sectors, quantity produced had increased rather than decreased, suggesting the importance of demand factors. That makes excessive inflation inevitable, whatever is happening on the supply side. Yes, Europe has high inflation, too, but they also have natural-gas prices seven times higher than we do, are entirely energy-dependent, have suffered a depreciating currency, and have much less flexible labor markets. And in Europe, if you look at core measures of inflation, they are elevated, but not nearly as elevated as core inflation was in today’s report.

The dollar is now about one-to-one in value with the euro, which hasn’t happened in a long time. Isn’t inflation supposed to weaken the dollar? What does it tell us that it is very strong instead?

The strength of the dollar reflects the fact that, despite our macroeconomic mismanagement, we have a very strong economy with immense investment opportunities and great capacity for entrepreneurial innovation. Also, because we have the most serious inflation problem, we’re likely to see the biggest moves toward tight money, which pushes up the value of the dollar.

Going back to last year’s bill — why do you think the Fed and so many other economists failed to anticipate its effects? The 2009 Obama stimulus drew a lot of criticism for being too small. I’m wondering if the maybe-understandable feeling that it was time to go big last year clouded some people’s judgment.

Here’s the issue: Economics is a quantitative science. The Obama stimulus bill was as large as politically possible at the moment but was, from an economic point of view, too small. Perhaps it should even have been twice as large as it was. But relative to the size of the GDP gap, the stimulus enacted in 2021 was perhaps five times as large as the Obama bill. And nobody suggested that the Obama bill should have been five times larger.

Democratic leaders are still trying to pass a pared-down version of their huge spending package. I know you were a proponent of the original Build Back Better legislation. Do you think Manchin’s caution on this new bill makes any sense?

Any country that has an underlying rate of inflation at 9 percent has to be very cautious. The right legislation that increased energy supply, reduced pharmaceutical prices directly, and reduced demand by raising revenue and cutting the budget deficit could improve our economic situation, even at this inflationary moment. But the bill has to be very carefully designed and very different from the very large spending programs that were conceived last year.

So you think those programs would have been unwise?

I’ll leave it at what I just said. Let me add: It would be very sad if the United States, having led the world in an international corporate-tax agreement that would prevent tax shelters from sheltering huge amounts of corporate income, were to knife that international agreement in the back by not passing the necessary implementing legislation. It would also be a lost opportunity if we could not do what was necessary to have a reasonable IRS that would raise hundreds of millions of dollars that are owed but not paid by tax evaders.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

More From This Series

- The Harris vs. Trump Races Hinges on These 3 Factors

- The Economy Is Finally Becoming … Normal?

- Paul Krugman Is Right About the Economy, and the Polls Are Wrong