When NYPD cops talk about the people they arrest, one often hears ugly slang like perps, mutts, psychos, and skels (a reference to the skeletonlike appearance of people addicted to drugs). It is a depressing exercise in dehumanization.

New York’s current public discussion about crime and public safety is only slightly more elevated. People arrested on suspicion of committing street crimes — arrested, mind you, not convicted — are often lumped together and portrayed as a kind of permanent, despised caste whose errant members should swiftly be “taken off the street” and jailed immediately, with guilt assumed and an actual trial treated as a distraction.

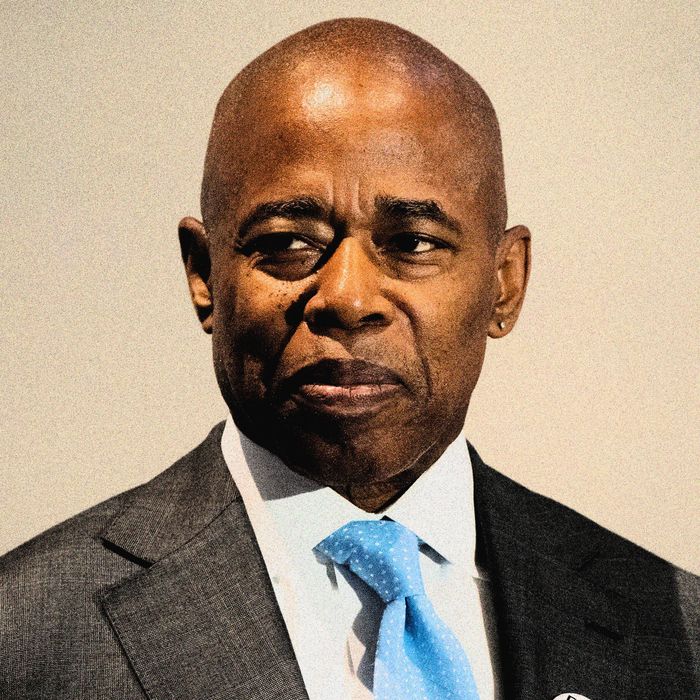

Mayor Eric Adams often slips into this language and mentality in what sounds like a holdover from his decades in the NYPD. “As soon as we catch them, the system releases them, and they repeat the action. When I say we’re the laughingstock of the country, this is what I’m talking about,” Adams said last week after bystander videos showed a wild scuffle between a pair of 16-year-olds and a team of cops at the 125th Street Lexington Avenue subway stop, allegedly for jumping the turnstile.

“How do we keep our city safe when the other parts of the criminal-justice system, they have abandoned our public-safety apparatus?” the mayor said. “We need to look at violent offenders, and this is a clear case of that.”

Nowhere in the mayor’s comments was an acknowledgment that a 16-year-old — even an out-of-control 16-year-old charged with serious crimes — is not just a “violent offender” but a child and that Rikers Island may be the worst possible place to send him.

On the very day Adams was complaining about a teenager being released pending his day in Family Court, four Department of Correction officers were arrested and charged with reckless endangerment and official misconduct in the tragic case of Nicholas Feliciano, an 18-year-old who hanged himself at Rikers in 2019. Eight jail officers and two Emergency Medical Services workers allegedly watched Feliciano hang for nearly eight minutes before cutting him down; years later, he remains hospitalized with severe brain damage.

Kudos to the lawmakers and other elected officials — including Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg — who are trying to keep New York on an even keel by following the law and refusing to play to the cheap seats.

Here’s what the angry politicians, law-enforcement officials, and media voices who keep beating up on Bragg and Albany legislators are missing: Much of New York’s current leadership hails from Black communities that have been on the receiving end of dehumanizing language, indiscriminate stop-and-frisk sweeps, and rough, jail-first policies. These leaders were elected by voters who have seen where the politics of rage and vengeance leads; many are parents especially determined to shield Black children from being summarily busted, beaten, and brutalized.

Bragg made the point shortly after his office won a long-overdue exoneration of Steven Lopez, the little-known sixth teenager falsely imprisoned in the notorious Central Park jogger case of 1989.

Lopez “was one of the six initially charged with the rape of the person we know as the Central Park jogger and then saw the two other trials unfold and the other five convicted based upon statements that we now know have been recanted or forensic evidence which has now been shown to be unreliable,” Bragg told me. “Remember his age at the time; he was 15 when first arrested. In the face of that intense public scrutiny, he then took a plea, which we argued was involuntary and therefore unconstitutional. The court agreed and granted our application, and the conviction’s now been vacated.”

Bragg is the same age as Lopez, and both grew up in Harlem at the same time.

“What was striking to me, reviewing all the records, is just the age of all the young men — in fact, I couldn’t even use the term young men — boys,” Bragg said. “I think about myself during that time. I was going back and forth from school to home, by the park, daily thinking about the things I was thinking about as a 14-year-old or 15-year-old. So I do think as we’re determining on a case-by-case basis what the proper outcome is, age is something that we’ve got to take into consideration.”

A few months ago, a state lawmaker told me about his frustration with Adams’s repeated insistence that New York should go back to sending 16- and 17-year-olds charged with serious crimes to adult criminal court rather than Family Court. “What the mayor’s talking about means sending a kid to prison for three and a half to 15 years, even for possessing a gun they never actually used,” the legislator said, shaking his head. “If you’re a teenager, that’s the equivalent of your whole life. We’re not gonna do that.”

That message needs to be heard and taken to heart at City Hall. The Democratic supermajority in Albany is led by Black lawmakers who have seen a lifetime of injustices like the Central Park case, which famously featured full-page ads in the New York Times by Donald Trump calling for the execution of five teenagers who turned out to be innocent. Today’s leaders were demanding reform during the era of unconstitutional stop and frisk in the aughts when hundreds of thousands of unnecessary police stops were made every year, overwhelmingly in Black and Latino neighborhoods.

“What happened here is that the yields were so low. Ninety percent of these stops didn’t result in any further law-enforcement action — not a summons, not an arrest, nothing — just you’re free to go, but that’s after you’ve been held for 20 minutes and humiliated in the street” is how retired federal judge Shira Scheindlin, whose ruling ended the NYPD policy, once put it. “For those of us who grew up with what we now call white privilege, we don’t understand what it’s like to not be able to get home without being stopped.”

“We have Family Court for a reason,” says Bragg. “It’s set up to have additional services and support for people who are juveniles below 18. How a case proceeds does matter for what your specific age is under the statute.”

Adams is determined to talk about crime frequently, despite evidence that constantly beating the drum is making New Yorkers scared to return to their offices or ride the subway. According to an analysis by Bloomberg News, there were an average of 800 stories per month about crime during the first few months of the Adams administration, compared with 132 stories per month across the entire eight years of Mayor Bill de Blasio’s.

Whether or not Adams dials back the frequency of his warnings about crime — which often cloud the good news that murders are down 31 percent compared with a year ago — he should move away from the simplistic formulations that describe our complex crime problem as a matter of locking up bad guys before trial.

More From This Series

- New York City’s Next Mayor Needs You

- How Desperate Will Eric Adams Become to Woo Trump and Get a Pardon?

- Finding Jordan Neely