This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

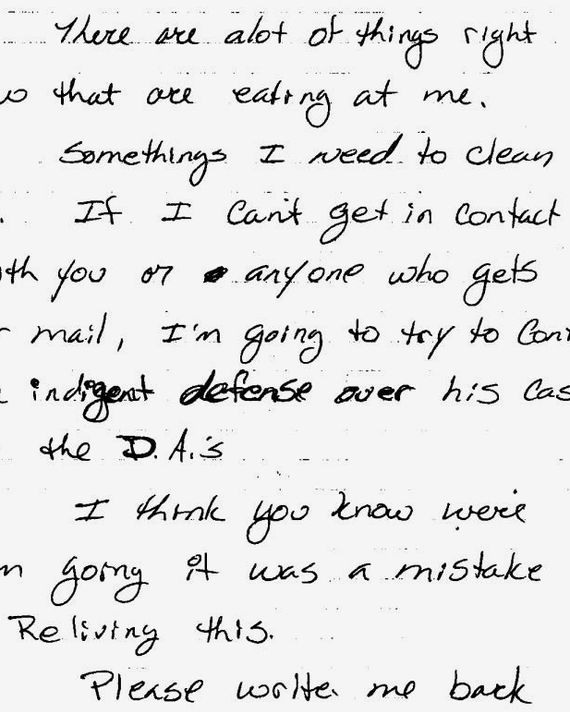

Nearly ten years into his life sentence for beating a man to death with a baseball bat, Justin Sneed sent a handwritten letter to his lawyer. “There are a lot of things that are eating at me,” he wrote from an Oklahoma prison in 2007. “Somethings [sic] I need to clean up.” He was referring to his testimony fingering Richard Glossip as the mastermind of the murder. “It was a mistake reliving this,” he wrote.

Sneed wrote the letter not long after the state’s court of criminal appeals voted to uphold Glossip’s conviction after his retrial and death sentence, and he seemed adamant to say more about his testimony, which the state relied upon to convict Glossip both times. (Glossip’s conviction after the first trial was thrown out because his lawyer failed to adequately defend him). “If I can’t get in contact with you or anyone who gets your mail, I’m going to try to contact the indigent defense over his case or D.A.’s,” Sneed told his lawyer. Within days, she wrote back. Rather than reassure Sneed that he had told the truth in court, she reminded him that putting the blame on Glossip was what spared him the death penalty. By insisting on his innocence and demanding a trial, Glossip had made the more costly choice. “Mr. Glossip has had two opportunities to save himself and he declined to do so both times,” she wrote to Sneed.

These letters were uncovered earlier this month, adding to a growing pile of evidence pointing to Glossip’s innocence. But the Oklahoma Attorney General’s Office is determined to move forward with his execution, scheduled for December 8. “Nothing has changed in the last seven years,” the state asserted in a pleading it filed, referring to Glossip’s 2015 attempt to have the appellate court intervene. “Not the facts, not the law, and not Petitioner’s guilt.”

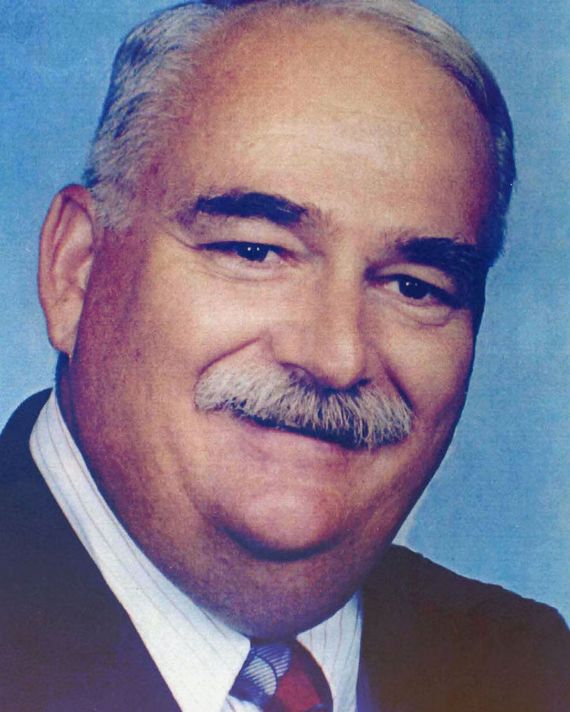

Glossip, 59, has a powerful and unlikely ally who believes otherwise: Kevin McDugle, a Republican state representative. If Glossip succeeds in his last-ditch improbable appeal to stave off death, it will be owed, in part, to McDugle’s efforts. A former Marine who served three tours in combat, McDugle, 55, is conservative to the core, describing himself as a staunch foe of abortion, champion of the Second Amendment, and defender of “Christian values.” And yet McDugle has been on a yearslong crusade to exonerate Glossip and has convinced more than 60 of his colleagues in the state legislature to join with him in demanding that the court order a hearing to explore Glossip’s claims, which include explosive allegations of police and prosecutorial misconduct.

If their effort fails, then, as McDugle has publicly pledged, “I will fight in this state to abolish the death penalty simply because the process is not pure.” The cost of halting the death penalty in a state that executes more people per capita than any other — 24 additional executions have been set to take place in Oklahoma over the next two years — would be Glossip’s life.

“It is a scary thing that these people don’t mind killing me knowing that I am innocent,” Glossip told me.

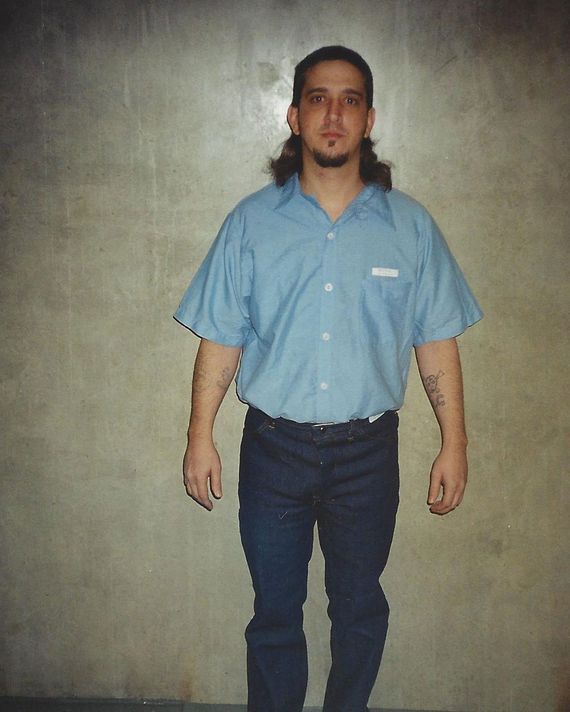

In the early morning hours of January 7, 1997, Sneed let himself into Room 102 of the Best Budget Inn in Oklahoma City, where the motel’s owner, Barry Van Treese, was sleeping. Sneed worked there as a maintenance man in exchange for room and board. Glossip, who was also living at the motel, managed the business. A methamphetamine addict with a history of thievery and violence, Sneed bludgeoned Van Treese to death and stole $4,000 from his car parked outside. Afterward, he stripped off his bloody clothes and stuffed them into a popcorn canister in the motel’s laundry room before fleeing.

Officers questioned Glossip at the motel and claimed he had provided shifting and inconsistent accounts of when he had last seen Van Treese, even claiming to have seen his boss leave the motel to run errands hours after he was already dead. A week later, law enforcement tracked down Sneed and arrested him, but lead detectives Bob Bemo and Bill Cook suspected Glossip had masterminded the murder and pressed Sneed to accept that theory repeatedly during his interrogation. In the first 20 minutes of questioning, Bemo and Cook, unprompted, brought up Glossip’s name six times, telling Sneed that he was going to “hang by yourself for this” but that they believed Glossip had put him up to it. If that were true, they suggested, there might be a deal to be made.

The detectives had already arrested Glossip, who insisted he was not involved. But their suspicions ratcheted up during his second interrogation, when he admitted that Sneed woke him up before dawn on January 7 looking like he had been in a fight and “told me that he killed Barry.” Later that morning, Glossip was seen outside Room 102 helping Sneed put Plexiglass over the broken window while Van Treese’s battered and bloodied corpse lay inside. Glossip never checked the room or alerted the authorities, and more than 12 hours passed before Van Treese’s body was discovered. And when Glossip was arrested, police found $1,800 in cash on him, which Sneed said he gave Glossip after taking it from Van Treese. Glossip later said he disbelieved Sneed’s confession because he was prone to spouting “weird stories,” later telling docuseries filmmakers, “If stupid is a crime, then I’m guilty.”

The district attorney’s office initially charged Glossip with acting as an accessory after the fact, but Bemo wanted more: Glossip’s protestations of innocence rubbed him the wrong way. “He was one of those kind of guys that irritates you, you know, with his comebacks,” Bemo told the filmmakers. Sneed was the key to proving that Glossip committed capital murder, and as Bemo explained, “It wasn’t any task to break Justin down.” Sneed subsequently signed a plea agreement saying he murdered Van Treese under orders from Glossip. The state told the jury Glossip acted because Van Treese was going to fire him for embezzling money. Sneed testified that he acted at Glossip’s instruction in exchange for half of the stolen proceeds. In return for his plea and testimony, Sneed received a sentence of life without parole.

Evidence to back up Sneed’s claim was “extremely weak,” according to the state’s court of criminal appeals, in its decision overturning Glossip’s first conviction. But Glossip was convicted at the retrial in 2004 and the jury once again imposed the death penalty. For nearly 20 years, Glossip battled unsuccessfully in state and federal court to have the verdict overturned.

Kevin McDugle had not followed Glossip’s case closely — criminal law did not interest him much. But several years ago, at the urging of his close friend Justin Jackson, a businessman and major donor to Republican politicians in the state, McDugle watched a 2017 four-part docuseries called Killing Richard Glossip. At the end, he told me, “I was iffy on innocence.” Still, doubts nagged at him.

No forensic or documentary evidence tied Glossip to the crime. Instead, the case turned on Sneed’s testimony. “The actual killer says Rich told him to do it, but he got off death row for saying that,” McDugle says. “That’s not real proof in my mind.” He contacted Glossip’s post-conviction lawyer and started reading everything he could get his hands on. What he learned made him feel sick — the state deliberately destroyed crucial evidence ahead of Glossip’s second trial, and none of what prosecutors told the jury added up.

The documentary evidence that would have either supported or refuted the state’s theory of Glossip’s motive and other aspects of Sneed’s story no longer existed because of the state’s own misconduct. Before the start of the second trial, the DA’s office — then under the leadership of Robert Macy, who prided himself on racking up death sentences, nearly half of which have been overturned — ordered the police to destroy a box of physical evidence. It contained numerous items, including a shower curtain Sneed claimed Glossip helped him hang over Room 102’s window after the murder and Van Treese’s wallet, which Sneed claimed Glossip handled. Most crucially, the box held all of the motel’s business records. Van Treese, deeply in debt and leveraged to the hilt, ran an all-cash business, stashing large sums in his car and avoiding banks whenever he could. His widow — who claimed that Glossip was shorting her husband even though Van Treese regularly paid Glossip a bonus for good work — said her paper records had been lost in a flood. As a result, Glossip could not disprove the state’s allegations of financial malfeasance and motive for allegedly ordering Van Treese’s murder.

After learning about the state’s misconduct and the absence, in his mind, of any credible evidence of Glossip’s guilt, McDugle met with representatives of the attorney general’s office. Their denials about the clear errors in Glossip’s case did not sit well with him. “They swore he was guilty because he had two trials and they raised up some papers in their hands and said, ‘Did you know that there was a lie detector test and he failed it?’” McDugle says. But the office refused to show him the results. Then McDugle learned that polygraph tests are notoriously unreliable and therefore not admitted as evidence in court. “Stuff like that, it just — they don’t want anyone to look under the hood at their engine.”

McDugle decided he needed to meet Glossip, so he went to visit him on death row in the state penitentiary. “Honestly, I wanted to get a feel for him,” he explained. Like McDugle, Glossip is a devout Christian. Glossip’s faith and generosity — even toward his captors — impressed McDugle. “Him as a person, I found him to be genuine, kind,” McDugle says. On three separate occasions in 2015, Glossip came close enough to execution that he was fed his last meal. Each time, he shared it with the guard tasked with watching over him. When McDugle asked why, Glossip told him, “There’s two things they can’t take away from you in prison and one is your gift of giving and one is your gift of joy.”

If Glossip were to be executed, he may experience an excruciating death.

In 1990, Oklahoma began using an execution method that relied on the intravenous injection of a three-drug cocktail: sodium thiopental, a barbiturate that induces a coma like state, followed by a paralytic agent, and finally a drug to stop the heart, causing death. Glossip was the lead plaintiff in a case challenging variations on this lethal-injection protocol, which reached the Supreme Court in 2015. As Justice Sonia Sotomayor noted during oral arguments, unless the prisoner is unconscious when the lethal dosage is administered, there is “a substantial risk of burning a person alive” from the pain.

But Oklahoma and many other states no longer have access drugs that would render a prisoner insensate. In the early 2010s, in response to a campaign by death-penalty abolitionists, manufacturers stopped producing sodium thiopental, the coma-inducing drug. In 2014, after trying and failing to acquire a similar barbiturate, Oklahoma substituted midazolam, a sedative, to execute Clayton Lockett. It didn’t work: Lockett woke up on the gurney, jerking and bucking against his restraints in a debacle the warden later described as “a bloody mess.” It took him nearly 45 minutes to die. The state, which had planned to immediately execute another prisoner, Charles Warner, was forced to delay.

Glossip, who was next to die after Warner, was being held in a room directly below the death chamber. “I could hear Lockett screaming,” he told me. “And then I heard Warner go ballistic, screaming at the top of his lungs, ‘You are not going to do this to me.’” Glossip, who had spent weeks in a freezing cell where bright lights blazed 24 hours a day in preparation for his own execution, was overcome with fear and despair. Warner got a reprieve but not for long. Executed on January 15, 2015, his last words were, “My body is on fire.”

Less than six months later, the Supreme Court ruled 5-4 that the lethal-injection protocols Glossip and other prisoners challenged were neither cruel nor unusual. The Constitution, the Court said, “does not require the avoidance of all risk of pain.” If anyone was at fault, they held, it was the condemned men. The law required them to come up with an alternative that would kill them more mercifully, and they had failed to do so. The ruling cleared the way for Glossip’s execution.

On September 30, 2015, minutes before he was scheduled to die, Glossip got an improbable reprieve from then-Governor Mary Fallin. The state had been caught ordering the wrong lethal drug — potassium acetate — and falsely claiming it was “interchangeable.” It turned out that the drug, which is also used to de-ice airport runways, had been used on Warner, but no one caught the error at the time. It was hours before Glossip was given the news. Stripped to his boxers, alone, and left to wonder what was taking so long, Glossip felt his sanity start to slip away. “I am surprised my brain didn’t snap that day,” he says.

The ensuing scandal led to the resignation of the penitentiary’s warden, the head of the Department of Corrections, and the governor’s general counsel. An execution moratorium was declared, and a commission was appointed to review the death-penalty procedures, issuing a nearly 300-page report a year later. The state ignored the commission’s recommendations, and on October 28, 2021, it executed John Grant. Once again, it used midazolam. Grant suffered convulsions and choked on his own vomit during the 20-minute procedure before he finally died.

McDugle had followed these developments with increasing alarm. By late February 2022, he had cobbled together a coalition of 34 lawmakers, including 28 Republicans, calling for an independent review of Glossip’s case and enlisted the global law firm Reed Smith to conduct a top-to-bottom review pro bono. More than 30 lawyers, many of them former prosecutors, spent 3,000 hours over the span of four months reviewing more than 12,000 pages of documents and interviewing dozens of witnesses. (Disclosure: Reed Smith has provided pro bono legal services to the University of San Francisco School of Law’s Racial Justice Clinic, which I direct.)

On June 15, McDugle released the findings of Reed Smith’s report at a press conference. Beside McDugle was Republican lawmaker Justin Humphrey, who chairs the House Public Safety Committee, and Stan Perry, a one of the lawyers who drafted the report. The results were damning. The law firm had exhaustively catalogued the errors in the investigation and trial, which ranged from police and prosecutorial misconduct to abysmal defense lawyering. Bob Bemo, the lead detective, came in for particularly harsh criticism. First, for coercing Sneed to offer up Glossip to save himself: “No individual facing a first degree murder charge would ignore this lifeline by police to implicate someone else,” as the report put it. Second, because Bemo later admitted he disbelieved the state’s theory: In 2017, he told the docuseries filmmakers that Sneed likely killed Van Treese because he “got a little carried away” after Van Treese fought back. But if this was not a premeditated hit job and simply a robbery gone wrong, then there was no role for Glossip to play.

Nor was it likely that Sneed gave Glossip any of Van Treese’s money. The cash in Sneed’s possession was smeared with blood; the bills recovered from Glossip, about $1,800, were clean and of a different denomination. Sneed was also likely lying when he claimed to have netted $4,000 — the law firm’s accounting of what Van Treese took back to his car hours before his death was closer to $2,800. Glossip’s money, he claimed, came from his selling off his possessions to hire a lawyer, and the law firm’s findings suggested his accounting was plausible. “No reasonable juror hearing the complete record would have convicted Richard Glossip of first-degree murder,” the report concluded.

Two weeks after the report was issued, Don Knight, the lawyer who has been representing Glossip in his appeals since 2015, filed a 120-page petition in the state’s appeals court seeking a hearing to explore the newly discovered evidence contained and new witness testimony from men who were jailed with Sneed in the months after his arrest. According to their accounts, Sneed used his girlfriend to lure Van Treese to Room 102 with the promise of sexual favors so that Sneed could rob him. When Van Treese fought back, they said, Sneed beat him to death in a methamphetamine-induced rage.

On August 4, McDugle and 60 other state lawmakers — most of them Republicans — signed a letter urging Attorney General John O’Connor to agree to hold a hearing on Glossip’s claims. But O’Connor’s office was unmoved and filed a lengthy response characterizing Glossip’s behavior as “deliberate and the product of a sinister mind.” The state dismissed the entirety of Reed Smith’s report as biased — the law firm has taken a public position opposing the death penalty — and asserted that Sneed’s regret over his testimony meant only he felt bad that Glossip was going to die. At best, the attorney general’s office concluded, Glossip’s legal team had assembled a few “snippets” of inconsequential new information. The attorney general’s office did not return emails seeking comment.

If the criminal court of appeals rules in the state’s favor, Glossip will be put to death as scheduled on December 8, unless the Oklahoma Pardon and Parole Board recommends clemency, which Knight filed a petition for last week. Of the four board members — the fifth recused himself because he is the trial prosecutor’s husband — three must vote in favor of Glossip. Were that to happen, the recommendation to the governor will likely be life in prison without the possibility of parole. (The board recommended life with parole last year in the case of death-row prisoner Julius Jones, but the governor gave him life without parole). This unlikely victory would, Knight told me, be a pyrrhic one. “Rich has told me he would rather die than serve life without parole,” he says. “I believe him. He knows what it is to face death.”

As the clock keeps ticking, Glossip is bracing himself to be served with his death warrant for a fourth time, which will trigger weeks of 24-hour surveillance in total isolation under bright lights that never dim. The first time this happened, in 2014, Glossip went on a 22-day hunger strike in protest. “They sent a lady from mental health up to talk to me 15 days into it, and she said, ‘Mr. Glossip I want to describe what is going to happen to your body if you keep starving yourself,’ and I said, ‘Ma’am, why don’t you describe to me what is going to happen to me when you put your drugs in my body and kill me?’ She just got up and left. It was the craziest thing I had ever heard,” he told me.

McDugle, meanwhile, has tried six times to bring to a vote bills that establish more legal protections for death-row inmates. All of them have failed, and his efforts have put him at odds with the attorney general’s office and the district attorney’s office, including the prosecutors who tried and convicted Glossip. (Emails to the Attorney General and assistant district attorneys who tried and convicted Glossip were not returned.) Knight told me that McDugle’s political future may be in jeopardy over his drive to exonerate Glossip.

McDugle remains defiant. “I don’t care,” he tells me. “I can’t stand the fact that there are innocent people on death row or doing life in prison — a good percentage of them.” In his improbable turn toward criminal-justice reform, McDugle sees that hand of God. “My purpose for getting elected is this very thing,” he says. “If it costs me my career, so be it.”

Glossip, too, has turned to God. “I am a very religious man,” he told me. “Hopefully the courts will do the right thing. I have to hope and believe because I am never going to let these people break me. Even though they are going to torture me just like they have been torturing me for years.” Still, Glossip has prepared for the worst. “I have made peace with death,” he says. “I have to.”