Novak Djokovic is a pseudoscience-loving nutter who thinks it’s possible to transform the composition of water with the power of thought. For the past year and a half, he has stubbornly refused to get vaccinated against COVID-19 out of some misguided notion of bodily autonomy. In 2020, during the height of the pandemic, Djokovic organized a charity tennis tournament in the Balkans that predictably fell apart after several players tested positive for the virus. After traveling to Melbourne earlier this year upon being granted an exemption to play in the Australian Open — a debacle that ended in his deportation — it emerged that Djokovic had recently mingled sans mask with people a day after testing positive for the virus. Most everything about his response to the pandemic has been terrible.

Unfortunately, American public-health policy is making him look like the reasonable one right now.

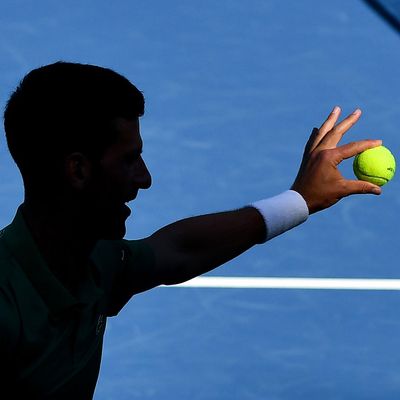

Djokovic, who won Wimbledon last month, would have been the clear favorite at this year’s U.S. Open, where he is a three-time champion. But he’s missing the tournament, which begins Monday, because of the American rule that any noncitizen or nonimmigrant must provide proof of inoculation before entering the country. Despite vowing to review the regulation earlier this month, the State Department hasn’t issued any new guidance since then. (The Biden administration could have issued a National Interest Exemption to let him into the country but sensibly passed on that option.) Djokovic officially withdrew from the Open on Thursday.

That this vaccination policy makes no sense in August 2022 hardly requires elaboration. When the U.S. announced the rule last fall — at a time when it seemed vaccination status and the potential to transmit the virus were at least somewhat closely linked — it was reasonable. But in a world of ultracontagious Omicron variants, when even pandemic-cautious cities and states have put a stop to almost every mitigation measure, the idea that the country is meaningfully preventing COVID spread with travel restrictions (that apply only to international flights!) is laughable. Pre-travel testing would be a considerably better method of preventing spread than anything involving vaccination. The list of good reasons to nix this foolish policy goes on. Even in January, there wasn’t a very solid public-health justification to keep Djokovic from playing in the Australian Open. But context mattered: Australians had endured a series of strict lockdowns lasting the better part of a year and were understandably upset about a celebrity athlete boldly flouting the rules on the heels of their suffering. Obviously, that kind of dynamic does not exist in the U.S. right now.

The travel policy isn’t just bad on the merits. It also helps solidify Djokovic’s status among anti-vaxx sympathizers, at least some of whom see him as a principled hero taking a stand against overzealous public-health restrictions. To be fair to Djokovic, he has never quite gone full anti-vaxx; has expressed some regret over the 2020 tournament; and, judging by his public statements, does not seem to hold it against anyone that he can’t play in some of the biggest events on tour. His forbearance in the face of such obstacles makes him an even more appealing avatar for people with all the wrong intentions. (As others have noted, he is applying the same otherworldly mental fortitude he displays on the court to this situation.) Yes, some COVID dead-enders would probably be championing Djokovic even if current travel restrictions were rational. But keeping wrongheaded rules in place just gives them ammunition. “Well, they’ve got a point on this one” is not a phrase one ever wants to utter about such people.

Djokovic could clear up this entire mess easily by simply getting vaccinated. Ultimately, he is to blame for his predicament, and it’s tempting to argue that he’s merely getting what he deserves. But continuing to punish him and other like-minded athletes for obstinance alone isn’t really defensible. And it’s not as if Djokovic hasn’t already paid a price. He missed Australia, where he probably would have won his 21st title, breaking the all-time majors record. (Instead, Rafael Nadal did that, then beat Djokovic at the French Open on his way to a 22nd.) He missed a good swath of the summer hard-court season, which mostly takes place in the U.S. and Canada, and will now miss another major as he approaches his late 30s. Oddly, he may be able to play the 2023 Australian Open since the country, which heavily restricted travel for so long, now has a looser entry policy than the U.S.

Although he has earned some grudging respect from crowds recently, Djokovic has never been popular with non-Serbian fans. (But boy is he beloved among Serbian fans, particularly of the internet-troll variety.) Among other reasons, the tennis-watching public seems eternally bitter that he intruded on the beloved Nadal–Roger Federer rivalry, put off by his attempts to be liked and unmoved by his almost flawless, sometimes machinelike game. Djokovic is often charming and funny, and though I’m a Federer partisan myself, I’d long thought he was saddled with an unfairly poor reputation. But his pandemic behavior wiped out any sympathy I once possessed for the man. I had the pleasure of attending last year’s U.S. Open final and thoroughly enjoyed watching Daniil Medvedev crush him, derailing Djokovic’s hopes of winning the first men’s tennis Grand Slam since 1969 and briefly keeping the all-time majors rankings at a three-way tie. This year, I was hoping to watch him go down to defeat again, preferably to someone not named Nadal. Instead, Djokovic’s shadow will loom over the proceedings the way it did in Melbourne a few months ago. Except that this time, the absence of the best player in the world feels like an injustice.