As much of the media industry sank beneath the digital waves in the last decade, the New York Times became something like Noah’s ark. If you could get aboard, you could ride out the storm and even be proud of the work you were doing along the way. Après le déluge, it’s emerged as the biggest news website in America, bigger than the websites of CNN, Fox, and its historic rival, the Washington Post. Two weeks ago, the Times seemed to rub it in with a story about how the Post can’t get its reporters back into the newsroom and is losing subscribers while “two of The Post’s top competitors — The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal — have added subscriptions since Mr. Trump left office.”

And so it ought to be smug sailing for the SS Sulzberger. Except his staff is about to mutiny over a contract they see as not giving them a fair share of the digital spoils, even as inflation eats into their pay and the company makes what many below decks see as expensive investments (The Athletic gets mentioned a lot). And so they’re refusing to return to the office this week as summoned. And suddenly there’s talk — even among the grown-ups in the Washington bureau — about the one thing that could really cause the Times to run aground: a strike.

“For a newsroom that’s been pretty fractious lately, it’s remarkable how much this has unified people,” says reporter Jeremy Peters. “I’ve never seen it this tense or on the cusp before, and I’ve been here for more than 15 years.” I heard from star reporters as much as from new enlistees, all of whom were fed up with how bedraggled the negotiations have become. “What you’re seeing is a lot of frustration,” says Nikole Hannah-Jones, who is definitely at the starrier end of things. “Everyone would like to see this resolved. People have been through a lot at the Times, and people love the Times, and people want to be treated fairly.”

I worked at the Times for a few years. I’ve seen a couple of mutinies. This one feels different. It’s not about whiny millennials or “quiet quitting” or ideological schisms. It’s not even about returning to the office, really. It’s about money, and each time the staff is reminded of the boffo subscriber count (9.17 million) and all the flotilla it has afforded their company to buy — Wordle and Serial and The Athletic — it just gets hotter down in the content engine room. It seems to them that the admiralty who run the place— a Sulzberger scion, a CEO who made $5.8 million last year, and an executive editor whose father co-founded Staples — are being awfully miserly. The breaking point came this week when the bosses tried to reward their return to the newsroom with a boxed lunch emblazoned with the Times logo. The lame lunch boxes seemed to taunt them, “Who says you can’t eat prestige?”

According to Times spokesperson Danielle Rhoades Ha, the current median salary for a Times reporter in the NewsGuild is $133,500. That’s the median. Big bylines and marquee hires make much more — many make less. Still, it’s steady, respectable work and more than many make these days at places like Condé Nast or, um, certain other magazine publishers.

Last year, the Times pulled in $2.1 billion in revenue. It spent $550 million for The Athletic. Now, the Guild is demanding an 8 percent annual raise and a cost-of-living adjustment on salaries. Guild members estimate the price tag for all that to be about $20 million.

Rhoades-Ha says, “We presented the NewsGuild with a wage proposal that would offer contractual increases of 10 percent over the remaining two and a half years of the new contract. That is significantly higher than in recent Times-Guild contracts.” Here’s where it gets complicated. Like, really complicated. That 10 percent figure is misleading — much of it has to do with this byzantine job-classification scheme they have there in which reporters are grouped by income bracket and job title. The more you earn inside your bracket, the smaller your raise becomes. For most mid-career reporters, who tend to earn more than the minimum guaranteed salary for their bracket, the company’s offer ends up amounting to something like a 2 percent annual raise by the time you factor in the expiration of their old contract and the end of what would be the new one in 2024. Journalists are famously bad at math. Economics reporters at the paper are helping decode it for their comrades, and people are sharing their salaries with one another, which has engendered further unhappiness inside the paper as some discover they are paid less than others or carry a less classy classification. (Are you a mere reporter, or are you a domestic correspondent?)

Timesfolk who stuck by the paper through the post-crash dark days are especially restive now that it’s back on top. Ken Belson, a sports reporter and 21-year veteran, joined colleagues in bombarding the brass with emails. “One year, we took pay cuts to help the company through financial rough waters,” he wrote. “During this time, many friends — some of the most talented reporters and editors in the newsroom — left The Times because they could not afford to stay. It’s time for you — the leadership of the paper — to tell the negotiating committee to reply to our wage proposals and stop being hypocritical. Enough already.”

Pete Wells, who started at the paper in 2006, says, “When I ran the food section, there was one budget cut after another. They took people away from me. I was down to a skeleton crew but, like a lot of people, I stuck through those very tight times. I think I always believed that things would turn around, and now that they have, it’s wonderful, but I feel very strongly that all of us should share in some of the rewards now.” (After he took the critic job in 2012, he went from management into the Guild.)

“It’s history repeating itself,” says Jill Abramson. “The staff has been working without a contract for years. Inflation is terrible. Of course they’re angry. I think the order to come back to the office is just one ingredient in their unhappiness. Their wages haven’t kept apace. That’s the real problem.” She became executive editor in 2011 in the midst of bitter labor negotiations. The staff walked out of the building for an hour, but the worst was averted. “The Times relies on an infamous union-busting law firm, Proskauer Rose, for labor advice, which, over the years, has made relations worse,” says Abramson. “A.G. should be all over this unrest, as I bet he is. I think he should think about new legal representation.”

That’s not the only thing A.G. Sulzberger and his CEO, Meredith Kopit Levien, might be thinking about. Just as the company is taking its sweet time to come up with a contract for its largest and highest-profile group, an activist investor called ValueAct has burrowed inside the Times, buying up a 7 percent stake in the company last month. ValueAct figures the revenues should be higher and is going to pressure the management to bundle up the new properties and wring more out of subscribers. That said, ValueAct doesn’t pose a very serious threat because of the way the company is structured; the Ochs-Sulzberger trust elects approximately 70 percent of the board.

But ValueAct can make noise if it doesn’t like the way Sulzberger and Kopit Levien are doing business. “Then it’s all about creating bad publicity to the controlling family, who, in order to keep their reputation, might do some stuff even though they are not obligated to,” says Zohar Goshen, a professor at Columbia Law and an expert on corporate governance. The last time an activist investor got inside the Times, in 2008, it got two people appointed to the board. One of them was Scott Galloway (who sometimes contributes to this magazine). “It’s an annoyance, and I was that annoyance,” he says. But he knows from his own experience (he left the board in 2010) that ValueAct can’t force the publisher to do anything he doesn’t want to do, and “as long as the Sulzbergers are happy with Meredith, she’s fine.” But it has to add to the stress on her. “The tumult in the newsroom,” says Galloway, “is the bigger issue.”

Sulzberger is very well liked by his rank and file, who consider him a trusty steward. But as the “tumult” grows, staffers see a split between the progressive “values” of both the paper’s news and edit pages and how it treats its employees. Timesian sansculottes who spend their days publishing editorial series like “the inequality project” are now talking about their young proprietor as if he’s the Marquis St. Evrémonde. “We’re so sanctimonious about all these other companies who pay their workers better than we do,” says one exasperated staffer.

But nobody ever went to the Times to make a lot of money. Even the CEO makes less than she could at another media company. The implicit bargain at the heart of being a Times lifer has always been accepting that you could make more doing something else but sticking around — because why would you do something else? But now that the Times would like us all to think of it as a tech company with a mini TV studio thrown in, how long can it go on paying its top content creators — back in the day, they were called “journalists” — as though it’s still an embattled print newspaper?

Reporters keep insisting to me that the modern media landscape has improved considerably and that Times management is deluded if it thinks people won’t start jumping ship. The reporters believe that, with the magic T on their résumés, they can set sail for paywalled pastures that are greener, if less widely read; Politico, Bloomberg, the Post, and the Journal would all pony up to poach them, they reason.

Perhaps. But here is one persnickety truth about the Gray Lady: With few exceptions, she does not care if you leave and won’t miss you once you’re gone. She likes to raid other ships for talent but looks down on anyone who would willingly disembark her own for what she considers a lesser vessel. There are only two destinations that have the power to really trigger Times masthead editors: The Atlantic and The New Yorker. Otherwise, it’s “Enjoy the free lunch box, and don’t let the door hit you on the way out.” There’s a lot of solidarity at the newspaper at the moment, but the great contradiction here is that it’s precisely because the Times is doing so well, has such massive reach, and is still, yes, economically stable that journalists will always line up to work there.

Unless, of course, there is a strike. Right now, sign-ups are being passed to Guild members for “strike school,” in which staffers would learn how to build up to a strike and get skeptical colleagues onboard. But so far, there has been no real planning, and the Guild has not even approached taking a strike-authorization vote.

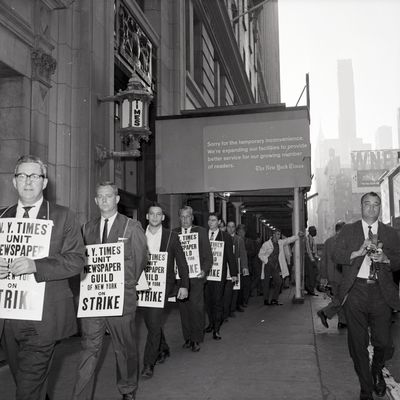

In the early ’50s, a strike resulted in the New York Times failing to publish for the first time in its history. That strike lasted less than two weeks. In 1962, there was a strike that went on for 114 days. It depressed Scotty Reston so much that he went on TV to read his Sunday column aloud: “It’s bad enough on the public, but think of a reporter. I’ve been fielding the Times on my front stoop every morning for 25 years, and it’s cold and lonely out there now. Besides, how do I know what I think if I can’t read what I write?” (There was one upside: The New York Review of Books was born as a result of that strike.)

But what would a strike look like today? Presumably, management would have some non-Guild reporters and editors commandeer some of the coverage, but you can bet those live briefings would grind to a halt. There might not be much left beyond word games, cookie recipes, and reruns of its Britney Spears documentary. Then the “paper” would be in a real jam.