“We do not sprinkle at the Abyssinian Church,” the deacon said proudly. “You will be held underwater until you are fully submerged.” This was an important but unnecessary reminder to me and a half-dozen other men, wearing little more than white smocks and socks, who were about to be baptized by the Reverend Calvin Butts.

This would not be like the baptisms of the Presbyterians, Espicopals, Catholics, or Methodists, who splash a bit of holy water onto the heads of infants to welcome them into Christendom. Baptists — like our theological cousins the Anabaptists, the Mennonites, and the holy-roller Pentecostals – wait until believers are fully grown and able to give consent to being dunked in waist-deep water. The residue of sin, sorrow, and human mistakes is left in the pool when the sputtering new Baptist stands up, washed clean and happily reborn.

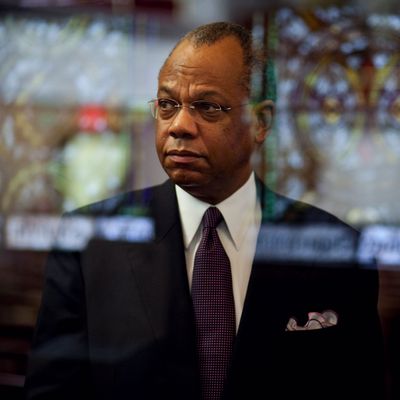

And so it was. The choir sang as the line of candidates walked, one by one, into the pool cut into the church’s gorgeous Italian marble pulpit. The Reverend Calvin Otis Butts III called each name out to the congregation. When it was my turn to take the plunge, Butts tipped me backwards with the help of a deacon.

This happened in the early 1990s, only a few years after Butts had officially become pastor of Abyssinian. His recent death at 73 from pancreatic cancer, much too soon, leaves our city without one of its finest preachers and steadiest leaders.

From the time of its founding in 1808 by a group of Black worshippers who refused the racially segregated seating of the city’s First Baptist Church, Abyssianian has grown to global fame, migrating from its first home on Worth Street to Harlem as it followed and fostered the growth of the city’s Black community.

The church’s thousands of members and the tumultuous, history-making leadership of pastor Adam Clayton Powell Jr., who simultaneously ran the church and served as New York’s first Black member of Congress, made it inevitable that Butts would be considered a possible candidate for office. But he never took that step, explaining why in a sermon earlier this year.

“I never did have a fire in the belly for politics. I never did,” Butts told the congregation in May. “I thought I did. I could be the mayor … shucks, I could be the governor. Man, might as well shoot for the big time: I could be the president,” he said. “But I never could find that fire. In the house of God, the beauty of the Lord, the love of God’s people — this is where I’m refreshed.”

Butts never ran for any office, which suited Harlem’s political leadership just fine: As young men, Representative Charles Rangel, David Dinkins, and their allies had come to power by toppling Powell and rightly saw Butts and Abyssinian as a force that could cause serious trouble. All manner of candidates would stop by the church, and Butts would acknowledge their presence, occasionally allowing them to address the congregation. The rare endorsements bestowed by Butts normally came outside the church building and included unorthodox picks like Republican governor George Pataki.

The real action at Abyssinian happened inside the sanctuary. Butts was an extraordinarily good preacher, summoning lengthy passages from the Bible at will and urging the congregation to change the world.

“Beloved, the most powerful movement that we are going to make today is when we decide that even more enthusiastically and aggressively, we take this gospel into the streets of New York City. The mayor, God bless him, is doing all he can — but the mayor is not going to be able to solve this violence problem just by locking people up. He’s not going to be able to do it. It’s not going to work,” Butts said in May. “What our young men and women need is a standard by which to live.”

Butts led mini-crusades against obscene, violent, and misogynistic hip-hop lyrics, on one occasion going so far as to rent a steamroller to crush CDs he considered demeaning. He once took buckets of whitewash to paint over some of the ubiquitous billboards for liquor and tobacco found all over Harlem.

But those stunts were the exception. The main work came as Butts took his flock through the Bible week after week, studying the text and praying fervently, looking for the divine spark and then finding a way to spread it outside. The symbolic baptism he gave me and others, he said, should continue throughout New York.

“Get up from this service and go into the world, teaching,” he urged the congregation. “Speak up for Jesus. Teach what you know. Baptizing them. Wash. Help people to clean up.”