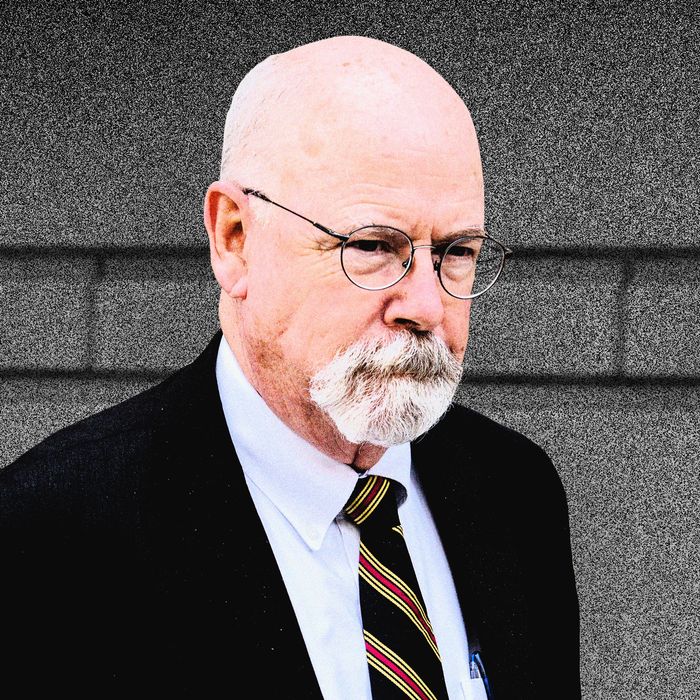

On Tuesday afternoon, a jury in Alexandria, Virginia, effectively delivered two verdicts in the third and likely final case brought by special counsel John Durham. The first was explicit: that the defendant, Igor Danchenko, was not guilty on charges of lying to the FBI about his role in the infamous Steele dossier. The second was implicit but equally pointed: that this whole yearslong prosecutorial effort — brought on by the corruption and dim-wittedness of Donald Trump and Bill Barr as a response to the Trump-Russia probe, supposedly promising to vindicate Trump as the victim of a witch hunt — has been a huge waste of time and taxpayer money.

When we last saw Durham’s team in court, they had lost a trial in the spring against a former lawyer for the 2016 Hillary Clinton campaign, but commentators in conservative media came up with a variety of excuses to explain this defeat, including that the presiding judge was an Obama appointee and that the District of Columbia, where the case was tried, is almost entirely comprised of Democratic voters. Neither of these things applied in the Danchenko case: This time, the judge was a George W. Bush appointee, and the Northern Virginia area is much more politically diverse.

The area is also a reliably law-enforcement-friendly jurisdiction, as I can attest from my own time working in the U.S. Attorney’s office in Alexandria. There are a bunch of law-enforcement offices and government contractors in the area, so the jury pool tends to favor prosecutors. The judges are also generally professional, efficient, and well-regarded — including Judge Anthony Trenga, who presided over the Danchenko trial — and like most, they tend to rule for the government. Trenga in particular has a reputation for being independent-minded (the first thing I learned about him was that he had tossed a financial fraud case brought by a friend of mine), and he is no anti-Trump partisan: He ruled in favor of the Trump administration on its Muslim travel ban in 2017 and has repeatedly ruled in favor of a business partner of Michael Flynn in a separate prosecution.

As a result of all this, Trenga’s frustration with and skepticism of Durham’s case against Danchenko, which was evident based on news reports in the run-up to and throughout the trial, was noteworthy even before the jury’s verdict. The case was nominally about whether Danchenko had lied to the FBI about two sources for claims that he relayed to Christopher Steele, but in a hearing last month, Trenga said it was “an extremely close call” whether it should go to trial at all given the thinness of Durham’s case, which, from the start, appeared to be little more than a convoluted vehicle to indulge conservatives and to discredit the Trump-Russia investigation. One part of the case concerned the sourcing for claims in the dossier about the so-called “pee tape,” but early this month, Trenga concluded that Durham’s theory of what had happened was short on actual evidence — “subject to a significant degree of speculation,” as he put it more politely — and he precluded the prosecutors from bringing it up at trial. Then last Friday, after Durham rested his case, Trenga dismissed one of the five counts in the indictment and suggested that he might do the same thing with the remaining four charges even if the jury ultimately convicted Danchenko.

Durham tried the case himself, and his performance sounded bizarre, if not downright bad. He attacked his own witnesses, which would be strange enough even if they weren’t also FBI employees testifying in a notoriously government-friendly jurisdiction. He seemed consumed with the relationship between the dossier and the opening of the Trump-Russia investigation and at one point said during his rebuttal closing argument that there was “no collusion” between the Trump campaign and Russia. This prompted Trenga to tell him, “You should finish up” — about as striking an admonishment as a prosecutor can get from a judge in the middle of a jury address.

Three and a half years since its inception, the Durham investigation has been a resounding failure. It has cost millions of dollars in the last two years alone, which doesn’t even include a trip to Italy with Barr in 2019 to run down evidence, and the only conviction resulted from a guilty plea from a low-level FBI lawyer named Kevin Clinesmith, whose case was grossly distorted by Durham and the conservative media.

Clinesmith was sentenced to probation by the judge for making a false statement, but it’s now clearer than ever that he should never have been criminally charged in the first place and probably would not have been in any other context. His offense was altering an internal email that was used to prepare an application to surveil Trump campaign adviser Carter Page, but Durham’s prosecutors eventually conceded that there was “no indication” that the episode resulted in the court being misled, and the judge eventually concluded that Clinesmith was simply “saving himself from work” by altering the email in question, which he had done in a way that he thought was accurate. This is not an excuse for Clinesmith’s conduct, but in the ordinary course, he probably would merely have been internally disciplined — not criminally prosecuted.

That case was the first indication to me that Durham and his prosecutors were not to be trusted, but I still somehow managed to overestimate their capabilities and trustworthiness ever since. After the Clinesmith case, I assumed there had to be something better coming. Instead, we got the prosecution of a Clinton campaign lawyer for an alleged lie that was so intricate that it’s not even worth revisiting, and then Danchenko, which was more provocative given the references to the “pee tape” and whatnot but still tortured and dubious from the start.

Altogether, Durham has easily put in the worst performance of any special or independent counsel since Ken Starr, who set the modern standard for wasteful, politically motivated investigations in the 1990s during the Clinton administration. The special-counsel investigation prompted by the leak of a CIA agent’s identity during the George W. Bush administration never resulted in charges over the leak itself, but it did result in the conviction of the vice-president’s chief of staff (though Bush later commuted the sentence and Trump pardoned him altogether). The Mueller investigation, of course, produced a bunch of criminal convictions (whatever its shortcomings).

Durham, by contrast, has produced less than nothing in court. He has irrevocably and undeservedly made three people’s lives much worse. He established no criminal conduct on the part of anyone in a senior position at the Justice Department or the FBI, which was supposed to be the whole point of this much-hyped exercise. And he has made a fool of himself in two different trials and jurisdictions in a matter of months.

Meanwhile, the principal defense of this effort among conservative commentators has been that Durham has done the public a service by publicizing derogatory information about aspects of the Trump-Russia investigation. The logic would never be tolerated by these people if their political allies were the targets of a criminal investigation as aimless, unproductive, and embarrassing as this one has been. (Just look at their reaction to the FBI’s court-authorized search of Mar-a-Lago that turned up over a hundred classified documents in Trump’s possession.) At best, the whole thing has been a glorified internal investigation run by a group of people who were perversely given subpoena power and the authority to indict people in the course of their work, and who proceeded to make a gigantic mess out of it.

It would be nice if this could all just be over, but Durham still has to complete a report, which may become public. That was Barr’s intention when he appointed Durham as special counsel in order to make it harder for the Biden administration to get rid of him, though in theory Merrick Garland could put a stop to that.

I do not say this lightly, but it is something that Garland and his advisers should now seriously consider. The logic for letting Durham proceed unimpeded to date has been shaky as a prosecutorial matter but understandable as a political one: There would be an endless freak-out among Republicans and the conservative media if Garland had intervened at any point, so why not let Durham take his best shot with a couple of weak cases and let the chips fall where they may?

It will no doubt be tempting to continue along this path, but the problem with the Durham investigation has not been that he revealed inconvenient facts, but that he is not good at his job, which is supposed to be rigorously developing and weaving together complex facts without resorting to speculation and without succumbing to confirmation bias, political bias, or both. The idea that this man might now be allowed to dump information that he has supposedly uncovered in the course of his work into the public domain — a report that will then be used by conservatives to claim that Trump was mistreated by the FBI despite Durham demonstrating for years now that he is not to be trusted in his handling of facts or evidence — is perverse.