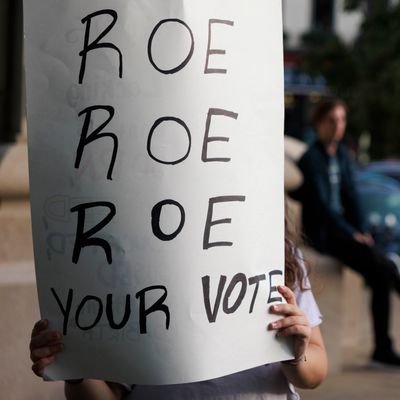

There weren’t high expectations for the Democratic Party going into the midterms. Aside from the historic trend that the controlling party in Washington normally loses seats in non-presidential years, polling suggested low energy from the party’s base and terrible approval ratings for President Biden. But then came June 24 and Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, the Supreme Court’s bombshell decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. That, says veteran Democratic strategist Tom Bonier, changed everything. After the stunning victory of pro-choice voters in Kansas on August 2, his firm, TargetSmart, analyzed new voter registrations and found that there had been a significant increase in women registering to vote in Kansas following Dobbs. Since then, he’s been eagerly sharing his findings on Twitter, on TV, and in op-eds. Though he stops short of saying this momentum will amount to a blue wave, he views the data as a good omen for Democratic chances in November.

I spoke to Bonier about the trends that he’s seeing following Dobbs, whether Democratic voter registrations rival that of Republicans, and the likelihood of either a red or a blue wave in the fall.

When did you first start to notice a connection between voter registration and the Supreme Court decision?

So, like a lot of people, I have to admit to being surprised by the Kansas election from August on the constitutional amendment to potentially remove protections for a woman’s right to choose from the state constitution. I had a baseline expectation or hope that it could be close. There was really only one public poll out there, and it showed a very close race. And so I was maybe only half paying attention to those results on Election Night. And I remember seeing the classic Dave Wasserman “I’ve seen enough” tweet that was less than 90 minutes after polls closed. And I thought, Well, that has to be wrong. For it to be a significant enough margin for the pro-choice “no” vote that it could be called that quickly would be extraordinary.

I just dug right in that evening and started looking at who registered to vote in Kansas, really setting up June 24 as an inflection point. So looking at who was registering to vote in Kansas prior to when the Dobbs decision was handed down and then how that changed, if at all, between June 24 and the August 2 election. And I was just absolutely shocked. Prior to Dobbs, it was exactly what you would expect. About 50-50 men and women, which is generally what it is, really regardless of what the state is you’re looking at. And then, looking at the post-Dobbs period, women accounted for just over 69 percent of new registrants. It’d be impossible to overemphasize how unusual that is. You just don’t see divergences from the norm anywhere near to that extent. You might see three or four or five points when any particular voting group is particularly more energized than another. But in this case, you saw women accounting for almost 70 percent of new registrants. So that was the first indicator that women were not only engaged by the Dobbs decision, but engaged at a level that really lacked any precedent.

Are you seeing this trend in other battleground states as well?

After looking and really digging into the Kansas voter-registration data, I started looking at other states around the country. Basically any state where the voter file had been updated by the state recently enough so we had enough of the sample size of new registrants since the Dobbs decision. What I found was, almost universally, women had increased their share of new registrants really across the country. And immediately it was difficult to discern a pattern because I think there were some assumptions, just in general, that perhaps the overturn of Roe v. Wade would have more of an impact in blue states and among core progressive voters. But what I saw jumping out was that some of the biggest increases in women registering to vote were in some of the reddest states. Not just Kansas, where perhaps it made more sense because there was a constitutional amendment literally about that issue, but also in places like Idaho and Louisiana and Alaska. Also in swing states with highly competitive statewide elections like Pennsylvania, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, North Carolina. And in fact, to the extent that the pattern wasn’t as stark, it tended to be in more Democratic states, like Oregon, for one. States where a woman’s right to choose is already enshrined in the Constitution.

How do those numbers break down demographically? Have you seen any increases in particular areas, like race and ethnicity, location and age?

I’ve mentioned women standing out, but the new registrants are much younger since Dobbs as well. Pennsylvania, where when you look at the women who are registering to vote after Dobbs, over half of them are under the age of 25. State by state, the youth share of new voter registrations really skyrocketed immediately after the Dobbs decision, and it’s been relatively sustained since then. You’re also seeing higher engagement among voters of color. So in Kansas, we now not only have the voter-registration data, but we can look at who actually cast a ballot in that election. The electorate set new highs for women in terms of share of the electorate. Women accounted for 56 percent of ballots cast in that election — generally, they are 52 to 53 percent. So it was a substantial increase in terms of their share of the electorate. But that result was also driven by a huge increase in younger people voting. Latino turnout was higher than the 2018 midterm general election.

People often expect midterm elections to result in low turnout since they occur in an off year without a presidential election. How much of a correlation is there between registration numbers and people who actually turn out to vote?

Two ways I’d look at this. One, generally new voter registrants turn out at a much higher rate than those who have been registered to vote for a longer period of time. There’s something about that act of registering to vote that generally leads to higher turnout among that universe of voters. Two, generally when you see a spike beyond the traditional pattern or beyond the historic norm of a group registering at a higher rate, that then does lead to that group, overall, turning out at a higher rate. I think that’s a really important point to emphasize here is the relevance of this spike in voter registration that we’re seeing isn’t really as much about a surge in first-time voters participating in this midterm election. Even in elections where first-time voters surge significantly, they generally don’t account for much more than 7 or 8 percent of the total electorate. But when a group is surging in new registration, that is almost always indicative of that group, in general, turning out at a higher rate. It likely indicates that women — who perhaps maybe have historically only voted in presidential elections or have been registered to vote for a while and they haven’t — will be coming out in this election at much higher rates.

There’s a tendency to look at young voters and say they don’t turn out during midterm elections. When you see these numbers, does it suggest that younger voters are more motivated than usual or do people tend to underestimate their level of motivation?

Obviously any demographic group votes at lower rates in midterms, but younger voters especially drop off more in turnout from a presidential election year to a midterm election year. And in fact, when you look at the last two decades and you look at these midterm elections, where the youth vote drops off the most is the election years where Democrats have lost by the widest margin, especially 2010 and 2014, where youth turnout was abysmal, frankly. And so there’s some understandable level of skepticism about younger voters.

We released an analysis in June 2018, similar to what we’ve done with Dobbs, where we looked at younger people registering to vote prior to the Parkland massacre and since. And we found that when you look at that point, younger people were registering at much higher rates after Parkland than they were before and we’re just seeing, in general, higher levels of engagement. In the end, younger people almost doubled their share of the electorate from about 7 percent of the electorate in 2014 to almost 13 percent in 2018. The blue wave that occurred that year wouldn’t have happened without this surge in young people voting.

What we’re seeing this year is similar in a lot of ways, but, in a lot of other ways, is more substantial. Not only because we’re seeing a higher surge in engagement than we saw in 2018, but that it’s more broad-based. It’s women in general of all ages, and it’s voters of color, who, again, are generally younger.

So when you say younger voters, that’s including men as well?

Yes. And what’s interesting is what we’ve seen is as we’ve released an analysis on women registering at a higher rate, one common response that I’ve seen is people saying, Well, that’s encouraging, but where are the men? Which is a fair question. And really what we’ve seen is this reaction happening in waves to a large extent where the immediate surge in engagement was coming primarily from women and again, more younger women. But then we’re seeing this secondary wave emerging across most states where younger men are now meeting that level of intensity and enthusiasm. And to your earlier question, we’re seeing this is a much more diverse group of voters who are registering to vote than those who were voting before. It’s primarily voters in urban and suburban areas in most states when you look at these new registrants. They’re somewhere between two-thirds and three-quarters of them are coming from urban and suburban areas in these states. But it’s not exclusively that, especially when you see these surges in places like Idaho, where certainly there’s not a significant urban and suburban core to the electorate.

I know that it’s probably hard to determine from numbers alone, but could there potentially be other motivating factors in addition to the Dobbs decision?

You know, even with the level of statistical analysis that you can apply to this data, it’s impossible to attribute the effect that we’re seeing to any one issue or any one moment or any one event. But in terms of a broader dynamic, I think you can’t ignore that. There are a number of factors that I’m certain are contributing to this level of engagement we’re seeing. You have the January 6 hearings before Dobbs. You’ve had, obviously, Trump’s reemergence into the public debate in a way, certainly around the Mar-a-Lago raids and now followed up by him being more public with rallies and that sort of thing. You’ve had Democrats actually enjoying legislative successes with the Inflation Reduction Act and getting through student-debt relief. And so I think all of those things are having an effect.

Of course, choice and Roe v. Wade are something that Democratic campaigns have been talking about and warning about the eventuality or the potential for it to be overturned for decades. As long as I’ve been working in Democratic campaigns, which is almost three decades, that’s been a central focus of Democratic messaging: If you elect this Republican candidate, then choice could get overturned. I think most Americans didn’t believe that Roe v. Wade could ever be overturned. So to the extent that the party warned about Republican extremism, I think there was a general sense that it was more rhetoric and less threat of action. This year, with the Dobbs decision, but also shining the light on January 6 and seeing how close we came in some ways to something that could have really subverted our democracy and the Republican candidates who are out there and now grabbing national attention, there’s just much more credibility in that messaging now. So that’s why you’re seeing voters reacting that way. So the sum total is yes, Dobbs might have been the spark or the tipping point that led to many people who had perhaps been on the sidelines getting engaged in this election.

In the run-up to November, Republicans have seen an increase in voter registrations as well, particularly in suburban areas. Is this a phenomenon that you’ve seen in the data, and how do those gains compare to what you’re seeing on the Democratic side?

Prior to Dobbs, Republicans were certainly seeing favorable numbers in terms of new voter registrations, and Republicans outnumbering Democrats in key areas, certainly places like Pennsylvania, Florida, North Carolina. But since Dobbs, we haven’t seen that. In fact, it’s been more inverted in those states where Democrats are now out-registering Republicans in some cases, like in Pennsylvania, by massive margins. Again, time will tell whether or not that’s indicative of Democratic voters turning out at a higher rate in general, and, potentially, do we see Republican voters not being as engaged? In Kansas, Republican voters came out at a pretty high rate. That’s worth noting. It wasn’t a case of Republicans staying home. So I don’t think there’s reason to believe at this point that Republican turnout will be depressed.

To me, I think it’s a question of this looming red wave that was apparent prior to the Dobbs decision and I think was treated as almost inevitable. Is there now a blue wave, if you will, or I guess what a lot of people are calling a Roe wave? Is there enough energy in that potential wave to meet the red wave and produce a relatively status quo result? If Democrats were able to hold on to the House and the Senate, even if the margins didn’t change substantially one way or another, I think that would be an incredible victory for Democrats. Or is it a matter where this Roe wave will just diminish what could have happened with a red wave, but Republican intensity will be high enough that they could retake the House, albeit perhaps by a narrow margin, and the Senate is still very competitive and perhaps within a seat or two for either party? That’s a possibility as well. I do think perhaps, at this point, the least likely outcome at this point is either party enjoying any sort of significant wave election where they’re seeing large double-digit gains in the House and we’re seeing the Senate balance tip by more than two to three seats in either direction. I think that’s the least likely outcome now.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.