By mid-morning on Saturday, October 28, 1962, I believed that it was highly likely that I had no more than 48 hours left to live and that the same was true of the entire population of New York City.

I had flown there from London six days earlier to report on the increasingly perilous confrontation between the United States and the Soviet Union — and, more personally, between President John F. Kennedy and the Soviet leader, Nikita Khrushchev — which had been triggered by the discovery that the Russians had built missile bases in Cuba. The missiles, tipped with nuclear warheads, had a range of 1,200 miles, putting a large part of the Eastern Seaboard within their reach.

On October 22, Kennedy ordered a naval blockade of Cuba, to prevent the delivery of any more missiles. From that moment, the two leaders held the fate of the world in their hands, each testing the nerve of the other, knowing that a single misstep could end in nuclear war.

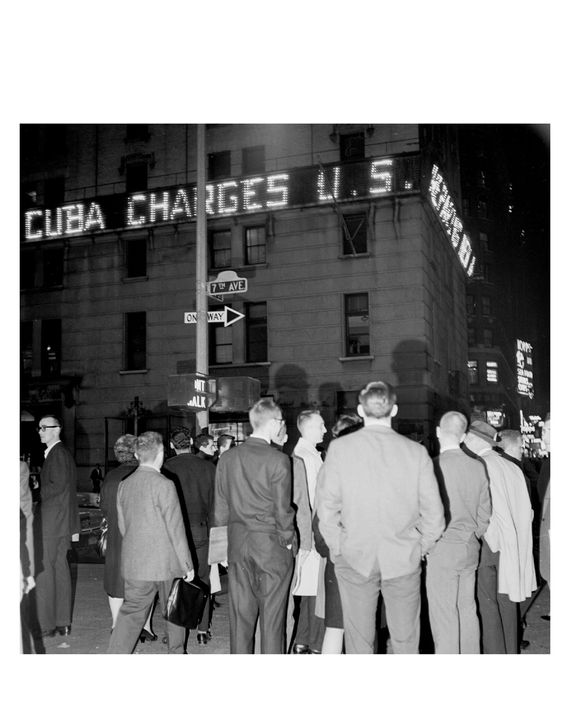

Much of the hope that this could be avoided centered on the United Nations headquarters in New York, where the acting secretary general, U Thant, was brokering talks between both sides without any visible signs of success. An early snowfall swirled around the great slab of the U.N. building on the East River, increasing the sense of bleakness. It became obvious to me, and the scores of other reporters who had flown into New York from around the world, that in the 17th year of its life, the U.N. was little better than a public theater where America and Russia traded insults.

If the fatal red button were pressed, that would happen in either Washington or Moscow. It is said that journalists write the first draft of history. In this case, it felt like a very thin first draft. We knew little of what was really going on behind the theatrics. By chance, at the U.N. I met, among the American reporters, one who seemed to be a Washington insider.

Douglass Cater was a soft-spoken Southerner who was the Washington editor of a biweekly newsmagazine, The Reporter, where he had helped build its reputation as an influential voice of the Atlanticist wing of the Democratic Party. We found we shared a problem in covering this story. I was the editor of a weekly British newsmagazine, Topic. And so, unlike most of the other reporters, who had daily deadlines, we both had to work up stories with a longer shelf life, a problem made more acute in this case because nobody knew the outcome.

We came to a deal. I would brief Cater on the political situation in London, where the prime minister, Harold Macmillan, was backing Kennedy but the Labour Party opposition was furious that Britain and America’s NATO allies had not been informed in advance of the naval blockade, and he would tell me what he knew from inside the White House. We would meet for breakfast the next day, October 28, at the Roosevelt Hotel, next to Grand Central Terminal.

Many of the tables around us were occupied by families on vacation in New York, showing little awareness of a world on the brink. Cater was grim. He said that news of military movements was hard to get but Washington reporters were drawing lots to go on an unspecified naval mission. Kennedy was managing the crisis with the man he most trusted, his brother Robert, the attorney general. They were being pressed hard by hawks in the military, led by the Air Force chief of staff, General Curtis LeMay, to bomb the Cuban missile bases. And, he said, although Kennedy was still negotiating with Khrushchev, he had agreed to the pinpoint bombing of the missile bases within days if there were no resolution. If that happened, I asked, wouldn’t it quickly escalate to a nuclear war? It was hard to believe otherwise, he said.

Beyond the visitors at the Roosevelt Hotel, New Yorkers were more aware that they could be living at ground zero. That morning, the New York Post ran a piece titled “Where to Go If Nuclear War Comes.” Basically, it led to buildings that displayed the yellow-and-black symbol for a fallout shelter, a black circle with three inverted triangles inside it. They were a Cold War feature, and there were hundreds of them in New York, mostly in the basements of offices and apartment buildings.

As it happened, I was better informed than most people about what a nuclear war would look like. Ten years earlier, as a conscript in the Royal Air Force, I was assigned to Supreme Allied Headquarters Europe (SHAPE) in Paris, recently set up under the command of General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the future president. Although I was near the bottom of the military ranks, the equivalent of a corporal, my work involved handling top-secret documents. (The vetting and surveillance was so rigorous that the security staff intercepted a letter to my mother describing the menu at the SHAPE canteen and warned me that no physical details of any kind about the headquarters could be disclosed, even, apparently, how good the canteen gravy was.)

Those documents revealed that NATO’s position was dire. The Communist land army in Eastern Europe, fielded by the Warsaw Pact powers including Russia, was so massive that its tanks could have rolled from East Berlin to the English Channel in a matter of weeks. If that were to have happened, western Europe could only have been saved by using nuclear weapons, and then only via a “first strike,” in which ours wiped out theirs before they could be launched. Thus was born the reliance for survival on the acronym MAD — mutually assured destruction.

Based on what I knew, the fallout shelters were useless. After a nuclear strike, New York would be uninhabitable for at least 100 years. Even if the basement of a building survived, there was no protection against the radiation. The only truly effective shelters were purpose built, located deep underground with air-filtration systems, a safe water supply, independent power, and months of food and medical supplies. Only two groups of people had access to those, the military command and the senior members of government. Without them, the living would envy the dead.

Nonetheless, state governors had been called to the White House to step up preparations for civil defense, and radio and TV stations tested their five-minute warning of imminent attacks. I remember one satirist of media mindlessness impersonating a TV anchor signing off with “Missiles heading for New York … more at eleven.”

My deadline was midnight on Sunday, October 29. I was writing the magazine’s cover story. There was as yet no lede. I had to dictate my copy over the phone to an editor in London. Overseas calls had to be booked in advance through operators at White Plains. I decided to file a first tranche of the story as a chronology of the crisis up to that moment. Given the demand, I had to wait hours to get through. The editor asked the obvious question: How was this going to end? I said nobody knew, but if this was a first draft of history, it might also be the only one, if it even got on the presses. He did not find that funny.

In London, I had left a young wife and a 10-month-old daughter. My last sight of them had already been clouded by a sense of foreboding, although I didn’t voice it. Now I wondered: How could I find a way of saying good-bye? A phone call didn’t seem adequate, and in any case, the lines to Europe were becoming harder to get. That Saturday night, I had dinner with some old friends in their East Village walk-up. We all had a lot to drink.

The greatest fear about what might lead to the failure of the MAD principle of nuclear deterrence is that, one day, a leader in charge of a nuclear arsenal will make a serious misjudgment of his adversary. That holds as true today with Vladimir Putin as it did sixty years ago with Nikita Khrushchev. And he must be as aware as anyone that in 1962, Khrushchev made a colossal misjudgment of his adversary.

Not long after Kennedy came to power, Khrushchev determined that the young president was weak as a leader of the free world. Their one and only meeting came in Vienna in June 1961. It was a disaster. Kennedy was ill prepared and later, talking to James Reston of the New York Times, admitted that Khrushchev had “just beat the hell out of me.” One result was that Khrushchev became strengthened in his belief that America and Russia were equal as two great powers and that any advantage lay with him, the stronger of the two leaders. After Vienna, former president Eisenhower complained that the nation was “in the hands of callow youth.”

That perception changed after Kennedy announced his blockade of Cuba. In my first report, I wrote that his blockade speech transformed his reputation overnight: “He ceased to be President and became Commander-in-Chief … smears of yellow-bellied leadership died in mid-utterance. In the gathering darkness, Kennedy recaptured the idolatry of his inauguration day — ironically, no longer as the leader of a new-age liberal rule, but as the gladiator entering the ring.”

By Friday, October 27, the Soviet leader had conceded that this was a new and resolute Kennedy, finally acknowledging that he had gone too close to the brink. He called a meeting of the Communist Party presidium at a villa on the outskirts of Moscow and told them that he was ready to dismantle the missile bases. Negotiations with Washington were under way.

None of this was known publicly until the morning of Sunday, October 29. Kennedy was preparing to attend Mass when he was informed of Khrushchev’s capitulation. He told an aide, “Do you realize we had an air strike all arranged for Tuesday? Thank God it’s all over.”

Not everybody was jubilant. At a meeting in the Pentagon with Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, General LeMay complained that “the Soviets may make a charade of withdrawal and keep some weapons in Cuba.” He insisted that “Monday will be the last day to attack the missiles before they become fully operational.”

News of the deal was released soon afterward. Kennedy called the three living previous presidents, Herbert Hoover, Harry Truman, and Eisenhower. Ike asked if Khrushchev had set any conditions. “No,” replied Kennedy, “except that we’re not going to invade Cuba.” Truman never asked any questions. Hoover said it was “a good triumph for you.”

And so, ten hours before my deadline, I had my lede. I wrote, “For six days the world was nearer to a nuclear Armageddon than it had ever been. Playing a deadly game of chicken, the two atomic superpowers edged closer and closer to the brink of a war which would have destroyed both.

“And, incredibly, at the very last moment in this iron test of nerves, it was Nikita Khruschev who cracked. Khruschev, the bellicose master of cold war strategy, had been outmaneuvered and made to concede a fundamental shift in the balance of power. The victor was John F. Kennedy, who for a week had been possessed of an extraordinary obduracy and borne the most awesome responsibility ever entrusted to an American president.”

We know now that it was a lot more complicated than that. RFK had been as vital to the outcome as his brother. In his masterly recounting of the crisis in his 2021 book, Nuclear Folly, Serhii Plokhy, director of the Ukrainian Research Institute at Harvard, describes how RFK had conversations with Anatoly Dobrynin, the Soviet ambassador in Washington, in which he tried to explain to Moscow just how much pressure the president was under from his military to retaliate by wiping out the missile bases. Dobrynin reported that the conversation was both an ultimatum — that there would be a military strike against Cuba if the missiles remained — and a face-saving offer to Moscow: If they pulled their missiles from Cuba, America would withdraw its missiles from Turkey, which were as close to Soviet bases in Eastern Europe as Cuba was to Miami. (The Jupiter missiles were virtually obsolete.) Kennedy would also guarantee that he would not invade Cuba. And that was the deal that ended the crisis.

Plokhy, drawing on Russian archives, also gives a detailed and gripping account of what was very nearly an inadvertent opening of a nuclear war. On Friday, October 27, three American frigates patrolling the blockade detected the presence below them of a Soviet submarine, eventually causing it to surface. As it did, the sub was buzzed by U.S. airplanes firing tracer bullets ahead of it. Some of the Russian officers concluded that a war had already started and readied a nuclear-tipped torpedo to fire at the frigates — the ten-kiloton warhead, if dropped on a city, would have killed everyone within a half-mile radius. At sea, the gigantic shock waves would have capsized the frigates and the radiation wiped out their crews. After a confusing exchange of signals, the Russians realized the Americans were apologizing. The torpedo was ready to be fired, but remained in its tube.

I never saw Douglass Cater again. After Kennedy was assassinated 13 months later, Cater joined the Johnson administration as a special assistant to the president and became an influential architect of the Great Society, shaping policy on education and health care.

Before I flew back to London, I realized that something had shifted — a change in mood that was hard to pin down. People were still trying to understand what had happened, how close it had been. Although nobody had yet put it into words, it suddenly hit me: America’s wars were no longer “over there.” The people of Europe — and Britain — knew what it was like to live every day in a war zone, always in the crosshairs. Now Americans had to learn to live like that, too.