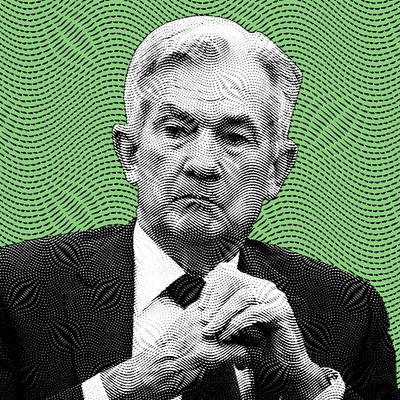

Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell has an image problem. It was less than three years ago that he was the guy in the meme making the money printer go brrr. But for the last 18 months or so, his role in American financial life has evolved: For a while, he was the “transient” guy who missed that inflation was happening; and in 2022 he’s been trying to recast himself as the sober economist with steely enough nerves to defeat that same inflation by raising interest rates higher than anyone expected. To date, that latter role has been his most challenging one.

On Wednesday, as expected, the Fed again jacked up the cost of borrowing by 0.75 percent, the fourth straight hike in interest rates this year — a move that makes the cost of just about anything that requires borrowing, from mortgages to credit cards, more expensive. But this hike was also different than the three prior ones – investors were hopeful that Powell would finally start backing off after this, that the worst was over. , At first today, the Fed’s announcement seemed to confirm that optimistic view. But as the afternoon wore on, and Powell took the podium in front of a room full of financial reporters and made it crystal clear that he isn’t done yet playing the tough guy and that he is prepared to continue inflicting his harsh remedies on the economy to fight inflation.

It’s been an objectively difficult time to oversee the world’s largest economy, and no matter how much of a sourpuss he has put on on or how often he talks about bringing “pain” to the American workforce, Powell has had to keep convincing the market – that is, all the investors in the world – that he isn’t about to chicken out on his plan to keep raising rates. Powell knows that, if Wall Street sees him as weak, inflation could surge as investors plow more money into the economy. But on the flip side, if he raises rates too high, he could tank the economy, pushing the country into a recession of his own making, and bearing the responsibility for millions of people losing their jobs.

This is why something intangible like tone — one could also say vibe — has become so important for the Fed. At Wednesday’s presser, Powell wore his characteristic authority with even more dourness than usual and seemed even a bit impatient in the face of questions about what he’s going to do next, and how long this period of austerity will go on for. “I’ve said at the last two press conferences that, at some point, it will become appropriate to slow the pace of increases,” he said. “So that time is coming, and it may come as soon as the next meeting, or the one after that. No decision has been made.” He’s right that there’s been lots of talk about the Fed slowing down on interest rate hikes, with something of a consensus emerging that the central bank would moderate starting at next month’s meeting. No one on Wall Street thinks they’re going to stop raising interest rates, only that they might increase it by a mere 0.5 percent — a signal that the Fed governors believe they’ve basically done enough for right now and want to wait and see how the all the rate raising they’ve so far affects the economy. But in the carefully worded world of central bankers, Powell spoke harshly and directly against all that hope that had built up on Wall Street.

And there’s plenty of evidence the economy has been feeling the sting of these rates. One major example is in home purchases. Wells Fargo, one of the largest mortgage lenders, has reportedly seen its loans drop by 90 percent from last year. Tech companies, which rely heavily on borrowed money and investors, have been some of the biggest losers this year, with Meta, Snap, and Amazon losing more than half their value this year from their peaks. There are bright spots: hiring is still resoundingly strong, with wage gains still high. But the Fed’s campaign to raise rates is expected to push more people out of work as a way to keep inflation down — and for the Fed, the continued strength of the labor market is yet more evidence that they need to keep going harder for longer on interest rates.

The next inflation report is next week, but the last two prints — both of which were above 8 percent annually — show that the problem of rising prices isn’t going to go away any time soon. (Since the last report, gas prices have also risen somewhat, which is outside the Fed’s control, but will probably bleed into their decisions going forward anyway). The message from Powell here is one of gloom, pain, sluggishness, gray clouds and icy winds, appropriate for the coming winter when the cost of heating is likely to sting most households in the US. “Reducing inflation is likely to require a sustained period of below-trend growth and some softening of labor market conditions,” he said. The projections from their very last meeting are already out of date thanks to recent employment data, he added.

When the Fed first came out with its announcement, a terse explanation of its interest rate hike, the markets – sensing that the general optimism about smaller rate hikes ahead was justified – rallied, with the Dow Jones Industrial Average shooting up by more than 300 points. ButPowell’s press conference soon throttled those animal spirits – after the Fed chair began speaking, stocks started to drop, and by the end of the day the Dow was down by more than 500. The message internalized by Wall Street was that, finally, this guy might be for real, and the optimism that the money printer would brrr once again was probably much too premature. Which, to be fair, is exactly how Powell wants it.