Almost a week after the 2022 midterms, there remains some uncertainty about the outcome of a few House races, and even about which party will control the chamber in 2023 — though Republicans are heavily favored to do so. What we know for sure is that Democrats hung onto the Senate with either 50 or 51 senators, depending on what happens in the December 6 runoff in Georgia — and that Republicans significantly underperformed expectations in Senate, House, and even gubernatorial races. So the question arises: Is there precedent for this sort of outcome, or are we dealing with something new and maybe even unsettling? Let’s look at some past midterm outcomes that look similar — depending on what happens in the next few days or week.

1934, 1998, 2002: President’s party gains House seats

If Democrats manage to maintain control of the House (which, again, is looking increasingly unlikely), 2022 will inevitably be compared to the three post–Civil War midterms in which the president’s party gained net House seats. It’s that rare.

But the precedents are pretty shaky. In 1934, Democrats gained nine House and nine Senate seats. That’s misleading, because they had gained 52 House seats in 1930 (when Republican Herbert Hoover was still president) and 97 in 1932 (when FDR defeated Hoover in a landslide) as the Great Depression gripped the country. They had pretty much reached a saturation point in Congress by 1934, which limited gains. It was certainly nothing like today’s closely contested partisan landscape.

In 1998, Democrats gained five net House seats and broke even in Senate races in Bill Clinton’s second midterm. That was a big surprise, which led almost immediately to Newt Gingrich resigning the House Speakership. It was generally attributed to a booming economy and popular unhappiness with Republican plans to impeach Clinton (which they proceeded to do after the midterms). But Democrats did not actually win control of either congressional chamber.

And just four years later, in 2002, Republicans made a net gain of eight House seats and two Senate seats, maintaining control of the House and regaining control of the Senate (which they had lost in 2001 when Jim Jeffords switched parties). That election was obviously affected by the trauma of 9/11 along with the focus it placed on national-security concerns.

What most separates 2022 from these three pro–White House midterms, other than the likelihood that Democrats will still lose control of the House, is presidential job-approval levels. In 1998, Clinton’s preelection job-approval rate (per Gallup) was 65 percent. In 2002, George W. Bush had a Gallup job-approval rate of 67 percent just prior to the midterms. There were no job-approval ratings publicly available in 1934, but FDR’s popularity was demonstrated two years later when he won 48 states and 61 percent of the popular vote. But Gallup put Biden’s job-approval rating in October at 40 percent. That’s a different universe of presidential popularity.

1962: Game-changing pre-midterm event

In John F. Kennedy’s first midterm, his Democrats lost a mere four House seats and gained three Senate seats. The election was preceded by the Cuban Missile Crisis in October of 1962, during which JFK’s leadership gave him considerable short-term popularity. You could compare that “game-changing event” dynamic to the backlash against the Supreme Court’s 2022 decision overturning Roe v. Wade, but otherwise the elections weren’t very similar. Democrats were in firm control of both Houses of Congress during this period, and Kennedy’s preelection Gallup job-approval rating was 61 percent.

1970, 1990: President’s party gets mixed results

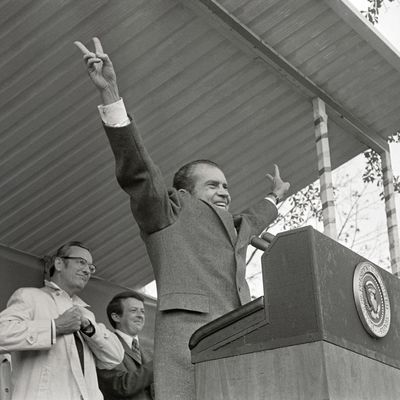

In both these midterms, Republican presidents with positive but hardly overwhelming preelection job-approval ratings (57 per Gallup in both cases) saw limited wins and losses. In 1970, Richard Nixon’s GOP lost 12 net House seats but gained two net Senate seats after running on a law-and-order message that would have sounded quite familiar to viewers of Republican ads this year. The Vietnam War and Nixon’s invasion of Cambodia galvanized voters in both parties as they began to fully polarize over that conflict. Despite Republican hopes of flipping the Senate, they fell four seats short, and Democrats made a startling net gain of 11 governorships.

In 1990, George Herbert Walker Bush was presiding over the military buildup that led to the quite popular Persian Gulf War, but he was dealing with serious economic problems. His Republicans lost just eight House seats and one Senate seat; it was the closest to a complete status-quo election as you could imagine prior to 2022 (net control of governorships didn’t change either). But Democrats retained firm control of both congressional chambers before and after the midterms.

So while the 2022 midterms carry echoes of previous elections, there’s nothing in the historical record quite like them. A big reason for this is the nature of today’s Republican Party — between its anti-abortion stance that led to Roe being struck down and Donald Trump’s enduring influence. And you probably have to go back to the Democrats of the late 1870s (after the contested presidential defeat of Samuel Tilden in 1876) to find a parallel to 2022’s numerous Republican election deniers. It’s certainly odd that an electorate as palpably unhappy with current conditions in the country collectively decided to change so little. So enjoy the experience of this suspenseful election if and when you can.

More From This Series

- J.D. Vance Explains His Conversion to MAGA

- Are Democrats the Party of Low-Turnout Elections Now?

- New Midterms Data Reveals Good News for Democrats in 2024