It was Tuesday afternoon in Washington, D.C., and something fabulous was unfolding. The White House was blasting Madonna on the South Lawn, where a surprisingly hot crowd for D.C. — many more chiseled men in good suits than you usually see around here — was grooving while waiting for their commander-in-chief. He was about to walk onto the lawn to sign into law the Respect for Marriage Act, or the RMA, as they’re already calling it here. (They love acronyms in D.C.) Among other things, it undoes the Defense of Marriage Act, which Bill Clinton signed in 1996 in one of his more cowardly acts of triangulation capitulation to right-wingers who’d accused him of being too pro–gay rights. Bubba felt it could help him win reelection; his campaign blanketed Christian radio across 15 states with ads touting that he’d signed it.

Versions of the RMA have been proposed since 2009, but it was finally made possible by the recent Supreme Court decision to overturn Roe, which raised the possibility that the 2015 gay-marriage decision, Obergefell v. Hodges, might go next. Well, that and the fact that, for the most part, the specter of same-sex marriage is no longer a very effective wedge issue. Mainstream Americans have come to support it, or at least no longer fear it, and the RMA passed with (some) bipartisan support. Plus the RMA protects the right to interracial marriage, on the chance the Supremes might go after Loving v. Virginia at some point too. And so, victory in hand, the moneyed and politically connected power gays of Manhattan, Hollywood, and San Francisco descended on the Potomac to party.

It all began Monday, the night before the bill signing. D.C. gays, deprived of celebrity after years of Trumpian tackiness, were aflutter at the presence of the gay bachelor Colton Underwood, seen dining at Georgetown’s Cafe Milano. Meanwhile, across town, HBO was throwing a party at the National Archives for Alexandra Pelosi, who has just released a documentary about her mother, Nancy. Paul Pelosi was there, in good spirits and looking a bit like Bogie in his black hat, which he has been sporting since being assaulted last month (and having right-wingers conjure up a lurid homophobic rumor to try to explain away the attack, which Elon Musk helped go viral).

The RMA was likely the final bill Speaker Pelosi will sign before relinquishing her gavel. I asked her what she would be thinking about as the president scrawled his pen across the bill. “My first words on the floor of the House were about HIV and AIDS,” she said, “and my last bill that I signed as speaker my first time was a repeal of the ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,’ and now one of the last bills I will sign and send to the president is this marriage-equality bill. So I’m very excited.” Just over her shoulder was the actual Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, encased in glass. She pointed to them and told me this is all really about one thing. “Freedom.”

Most people got into town Tuesday morning, the day of the signing. The first-class car of the 10 a.m. Acela from New York to D.C. was apparently packed with Manhattan power gays, some of whom could be heard frantically dialing their White House connections, begging to be moved into the VIP section at the bill signing. Spotted among them was Fred Hochberg, the former president of the Export-Import Bank of the United States, theater producer and political speechwriter Alex Levy, and Ken Mehlman. He was a top official in the (fairly homophobic) George W. Bush administration, but most of that was basically forgiven after he became a leading Republican to fight for same-sex marriage. Also on the train was David Mixner, the godfather of gay rights, and people were lining up in the aisle to pay their respects.

Among other things, Mixner was an important bridge for Clinton to the LGBTQ+ electorate. In 1992, Clinton reached out to gay Americans, saying, “I have a vision, and you are part of it.” His inauguration was really the first time gays flocked to political Washington to party proudly. It was considered a big deal when Mixner danced with another man at the inaugural ball. That year, Vanity Fair published “The Gay Nineties,” a famous piece that went “inside the new gay-and-lesbian power structure.” But when gay rights seemed to become a political liability, Clinton pulled the plug, signing “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” and the Defense of Marriage Act, and Mixner had a falling out with the Clintons.

Not everyone who pioneered marriage equality in those days got invited to the bill signing in D.C. on Tuesday. Andrew Sullivan wasn’t there. “Look, of course it’s a good thing, I’m glad it passed, and when they get this kind of legislation, they’re going to celebrate it,” he told me. “But this is really about donors. It’s about rewarding the very, very tight circle between the big-money gays and the Biden White House. It’s a completely closed circle, and there is no ideological diversity or political diversity allowed. And that is not the spirit of the marriage-equality movement; it never was.”

We’ve arrived at an interesting moment. Twelve Republican Senators voted for it thanks in part to it being signed off on by some major religious groups (including the Mormons). On the other hand, one Republican cried on the floor of the House while protesting the bill, several others reversed and voted against it, and the ones who were in favor caught hell for it. Iowa Republicans censured Joni Ernst for voting for the bill.

Politicians tend to be risk averse and interested most of all in self-preservation — traits shared by closeted gay people, who by definition couldn’t exactly press for rights they refused to acknowledge they needed themselves. Jamie Kirchick, the author of Secret City, an excellent new history on gay Washington, told me that if he has one observation on the subject, it’s this: “Washington was simultaneously the gayest and most anti-gay city in America, which was appropriate because it’s the capital of hypocrisy. I mean, the Reagans were surrounded by homosexuals.”

Donald Trump’s administration was, in some ways, an improvement from the open homophobia of the Republican past. He empowered gay officials such as Richard Grenell. (And, let’s face it, Melania was a camp queen.) But the Trumpian right has taken up a new line of attack against LGBTQ+ people that is, in a way, a very old one — all this talk of “grooming” is retro smearing. And Ron DeSantis doesn’t seem as if he’ll be a friend to the gays. (He could certainly use some advising on wardrobe.)

I asked men and women on the lawn and around D.C. this week if, in light of the new bill passing, Republicans are now considered allies. “Not really” was the consensus. But is it okay to be bipartisan in the bedroom? “Not really” was the consensus.

“There’s no question that there are moments in the political and social life of this country — and this is one of them — when it becomes convenient for some political figures to attack vulnerable people,” Pete Buttigieg told me while standing on the White House driveway. “We’ve seen attacks on the LGBTQ community taking many forms, and, you know, even as we’ve had these advancements of the law, it’s clear that there’s really a rising tide of this kind of targeting and even hate and sometimes violence, so it’s something we have to continue to be vigilant about.” And yet Washington is a pretty gay place these days. “Probably always has been,” he said. Does he think we’ll ever see a gay president in our lifetime? “Hope so,” he said with a smile.

The Human Rights Campaign had an after-party at its headquarters. Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Tammy Baldwin were there, as was the activist Charlotte Clymer. Some people at the party were chitchatting about how hot Hunter Biden is. But the lighting was bad in there and the crowd a little uptight. One young man scolded me for saying “gay” instead of “queer,” which is apparently “more inclusive.” (Talk about “Don’t Say Gay”!)

There was a better after-party happening nearby at the Sofitel. Certain power heteros were permitted entry: I saw Adam Schiff, Cory Booker, Pramila Jayapal, and Kirsten Gillibrand mingling. “They know where the money’s at,” cracked one partygoer standing a few feet away from gay gazillionaires Tim Gill and Sean Eldridge.

Jerry Nadler was there, too. He’s the one who originally authored the RMA bill years ago. He said he thinks it was able to finally be passed because “so many people have come out. Everybody knows a brother-in-law or a sister or a nephew or a niece or somebody, and that gives a lie to the old mythology about gay people being somehow unnatural or whatever.” But what is the representative’s official stance on gay divorce? “Gay divorces are like straight divorces,” he mused. “Some are amicable. Some are not so amicable.”

“His chief of staff got gay divorced,” said his chief of staff, Amy Rutkin. Her split from Valerie Berlin, co-founder of the communications firm BerlinRosen, was the topic of much gossip in power-lesbian circles. I asked what her gay divorce was like. “Like all divorces, sad,” she said, taking a big sip from her vodka martini. “But we were lucky to have the ability to do each of the things — go get married and have the legal protections afforded to us.”

There were cool, high-powered lesbians all over the place at this party. At the bar, the political operative Hilary Rosen was talking to Heather Rothenberg, a top dog at YouTube, who was there with her wife, Ellie Schafer, who worked in the Obama White House. Rothenberg had flown in that morning on a red-eye from San Francisco. She sipped Champagne and told me she loved seeing “so many people in D.C. who have gone to other places but who have all come back to mark this moment and mark all of the hard work that got us here and the work that still lies ahead.”

The night before, at the HBO party, I’d run into Ned Martel, the former Washington Post editor who fled D.C. to work as a producer at the gayest company in Hollywood (Ryan Murphy Productions). He was there with the actor Charlie Carver. Congressional staffers clamored for a selfie with the hottie Teen Wolf. Carver is a native San Franciscan, and he loves his representative. “She is a gay icon, 100 percent,” he said. “Why? Because she’s a strong, ferocious woman who doesn’t compromise her values and yet still leads with kindness and sass.”

He was standing near our nation’s founding documents. So, “fuck, marry, kill”: George Washington, Ben Franklin, and Abraham Lincoln. “Well,” said Carver, furrowing his brow, “I’d say fuck Abraham Lincoln, marry George Washington for legacy, and kill Ben Franklin.” But not until after he discovers electricity. “Exactly.”

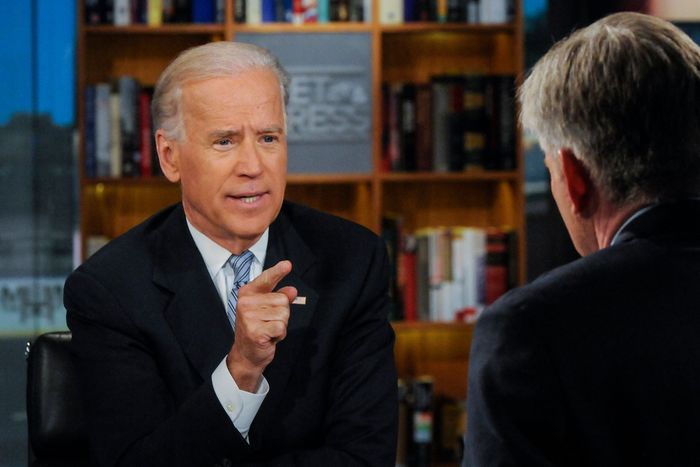

Carver and Martel took me to the Dupont Circle gay bar JR’s, where we bumped into Chad Griffin, the former head of the Human Rights Campaign who helped get the Obama-Biden White House to come out for gay marriage in 2012. It was Griffin who, at a fundraising dinner being held in the home of a gay couple, pointed to the couple’s two young children and asked then-Vice-President Biden how could he not support equality for LGBTQ+ families. Biden was so moved — “It was one of the most poignant questions I had ever been asked in my life,” he would later say — that he finally just spit it out: He did support it. A few days later, he appeared on Meet the Press and said pretty much the exact same thing. That famously caught the White House off guard and set off a chain of events that resulted in Obama being forced to finally publicly embrace gay marriage. (In a subsequent interview with Robin Roberts, a pouty Obama characterized his veep as having been “a little bit over his skis.”)

On the White House lawn at the bill signing this week, Biden replayed the clip of himself on Meet the Press. He was so proud of it. “Some of you might remember, on a certain TV show ten years ago,” he told the crowd of 5,300, “I got in trouble.”

I remembered what Griffin told me the night before at JR’s. “There is no question that President Biden is the most pro-equality president in the history of the country.”