The state of the economy is weird.

The U.S. gained 263,000 jobs last month and grew at a nearly 3 percent annual clip in the third quarter of this year. At 3.7 percent, the nation’s unemployment rate remains near historic lows. Meanwhile, inflation — long the bugbear of the Biden economy — appears to finally be abating. The consumer price index edged up by just 0.1 percent between October and November. The annualized inflation rate now sits at 7.1 percent — down from a peak of 9.1 percent in July. What’s more, the U.S.’s most politically sensitive price — gasoline — is lower today than it was a year ago.

In other words, payrolls have been expanding and economic growth has been accelerating while consumer prices have seemed to be stabilizing. Look up from this data, and you may start to see the outlines of a Goldilocks economy, defined by low inflation and high employment, taking shape on the horizon.

But that isn’t what most economists see. Forecasters surveyed by The Wall Street Journal in October put the probability of a U.S. recession next year at about 63 percent. Some analysts, like those at asset manager Vanguard, say that a 2023 recession is all but certain.

And not without reason. With demand for goods and services outpacing our economy’s capacity to produce them at (relatively) stable prices, the Federal Reserve intends to continue suppressing spending and investment by raising rates. As borrowing costs mount, consumers tend to pull back and employers slash investment. This leads to lower demand for workers, which puts downward pressure on wages and, therefore, on prices. But the cost of fighting inflation through higher interest rates has historically been higher unemployment and recession.

The Fed rapidly raised rates in 2022, and while it is poised to slow down next year, it has no intention of changing course. Rate-sensitive sectors are already reeling with new U.S. home sales cratering. In November, retail sales fell by 0.6 percent, the sharpest monthly drop all year. Meanwhile, manufacturing output is falling, firms are delaying capital plans, CEOs are losing confidence, and households are burning through their savings.

For these reasons, virtually all analysts believe that the U.S. economy will slow next year. But the ugliness of the economic outlook is in the eye of the beholder. Some forecasters anticipate a painful worldwide recession followed by a lackluster — yet persistently inflationary — recovery. Others maintain that the U.S. will achieve price stability without suffering a downturn. Here’s the reasoning behind their disparate views.

Why the U.S. economy might be headed for a painful recession and lackluster recovery.

The case for pessimism begins with a few indisputable data points. Thanks to inflation, Americans’ real purchasing power has been falling for more than a year, as Vanguard illustrates in a recent report.

Normally, a sharp decline in real wages would trigger a pullback in consumer spending and, thus, a slowdown in growth. But the pandemic swelled Americans’ savings: The vast majority of workers retained their jobs during the COVID crisis yet had their wages supplemented by relief checks and their spending constrained by shutdowns. Between 2010 and 2020, U.S. households saved an average of 7 percent of their income. In April 2020, that rate shot up to 33.8 percent. By the summer of 2021, Americans collectively held $2.3 trillion in their savings accounts.

Thus, instead of responding to falling wages by tightening their belts, consumers have drawn down their stockpiles of cash. But that is not a durable recipe for sustaining demand. In October, Americans’ personal savings rate fell to a piddling 2.3 percent. At some point, U.S. consumers will collectively recoil at their balance statements, cringe at the cost of credit — then, perhaps, take a peek at their emaciated 401Ks — and start striking discretionary purchases from their shopping lists. Indeed, November’s retail-sales data suggest that we have already reached that point. This drag on economy-wide demand is exacerbated by sharper contractions in the sectors most sensitive to rising interest rates. Sales of new homes in the U.S. are already down 25 percent this year.

All this said, no one disputes that an economic slowdown is nigh. What’s at issue is the severity of that slowdown and the quality of the ensuing recovery.

Therefore, the core of the pessimists’ case has less to do with discrete data points than with a big-picture theory of how the global economy is evolving.

Specifically, BlackRock’s macro team, Allianz adviser Mohamed A. El-Erian, and other bearish analysts argue that the economy is becoming persistently more vulnerable to inflation as a result of three structural changes.

First, across the developed world, populations are aging, and this top-heavy demographic pyramid is starting to wobble. A large number of Americans were already on the cusp of aging into retirement before the pandemic, but this process accelerated by nudging 60-something workers onto the labor market’s sidelines. The labor-force participation rate fell sharply in 2020 and has yet to return to its pre-pandemic level. According to BlackRock, this is primarily due to a wave of retirements, which means that the U.S. labor supply will never return to its 2019 size.

Aging populations are theoretically inflationary. And for a simple reason: More retired people means fewer workers contributing to the supply of goods and services but not fewer consumers demanding them. If an aging population reduces demand in some sectors, however, it swells it in others. Developed economies will need to find a way to support high and rising demand for health-care services with small and declining prime-age workforces.

The second pro-inflationary structural change in the economy is the death of “just-in-time” global supply chains. This shift is proceeding on two fronts. First and most critically, globalization is kicking into reverse thanks to intensifying geopolitical rivalries. This is most evident in the West’s ongoing effort to end its dependence on Russian commodities in the wake of the war in Ukraine. But U.S. attempts to restrict trade with China — and Beijing’s own plans to reduce its economy’s reliance on foreign markets — are potentially more significant in the long term.

In any case, governments’ desires to prioritize the geopolitical friendliness of major supply chains over raw efficiency put upward pressure on inflation. For four decades, the price of goods in the U.S. was deflated by China’s labor discipline and cost-minimizing global supply chains. Now, geopolitical imperatives will render global production more inefficient and, thus, goods more costly.

At the same time, the pandemic and war in Ukraine have alerted corporate managers to the hazards of prioritizing efficiency over resiliency. To guard against future shocks, firms will now be more inclined to build some slack into their supply chains and retain larger inventories — moves that will increase the robustness of their operations at the expense of higher production costs.

The final structural tailwind to inflation is the green transition: The more critical minerals needed for electric-vehicle batteries, the fewer available for cell phones. The more construction laborers needed for building transmission lines, the fewer at the housing sector’s disposal.

Furthermore, there is a risk that some forms of fossil-fuel production may decline faster than clean energy can rise to replace them — whether for technical or political reasons. Even in the rosiest scenario, developing economies will remain heavily dependent on fossil fuels for the next decade. But maintaining the productivity of a sector that is widely understood to be doomed to decline is not easy, as both capital and talent migrate elsewhere.

Therefore, until the green transition reaches its mature stage, the global energy system may grow more vulnerable to shortages and shocks while the resource demands of the green buildout may put upward pressure on the prices of various commodities and forms of labor.

In the near term, all of this increases both the likelihood and potential severity of a recession next year. That’s because anything that constrains the capacity of the economy’s supply side to grow in response to demand — whether that be a shortage of prime-age workers, inefficiencies in supply chains, or energy shocks — will put more pressure on the Federal Reserve to achieve price stability by throttling demand.

In BlackRock’s account, if the Fed is truly committed to bringing inflation back down to 2 percent, it will need to engineer nothing less than a deep recession, since the U.S. economy’s productive capacity has fallen far off of its 2019 trend line.

BlackRock doubts that the Fed will actually have the stomach for that, arguing that the “politics of recession” will kick in and the central bank will be forced to ease up on rates. Critically though, persistent inflation will, in this account, nevertheless prevent the Fed from switching gears completely and fighting a recession through aggressive rate cuts and quantitative easing — as it did during the 2009 and COVID downturns.

This means that the U.S. is liable to suffer a significant increase in unemployment in 2023, followed by a lackluster recovery characterized by weak growth and a (relatively) elevated price level.

This said, precisely because the U.S. economy is suffering from a labor shortage, the unemployment rate is unlikely to rise to the heights witnessed during the last two recessions. Vanguard’s macro team takes a bearish view of the 2023 economy overall, predicting that U.S. GDP will grow by a piddling 0.25 percent (the consensus estimate is closer to one percent). Still, it does not foresee unemployment rising much higher than 5 percent in the New Year.

The pessimists’ case is therefore as much about the medium term as it is about the immediate one. The problem is less that next year will be rough economically than it is that the ensuing years will be disappointing — at least relative to the economy we enjoyed back in 2019.

Why the Fed might be able to bring prices down without triggering a recession.

To a degree, the case for economic optimism inverts the logic of BlackRock’s counsel of despair. The latter stresses that a great deal of inflation derives from supply constraints and concludes that the Fed will, therefore, struggle to bring down prices without draconian measures.

Optimists emphasize the contribution of supply-side bottlenecks to inflation. But they see this as a cause for thinking that the Fed can bring down prices without tipping the economy into recession.

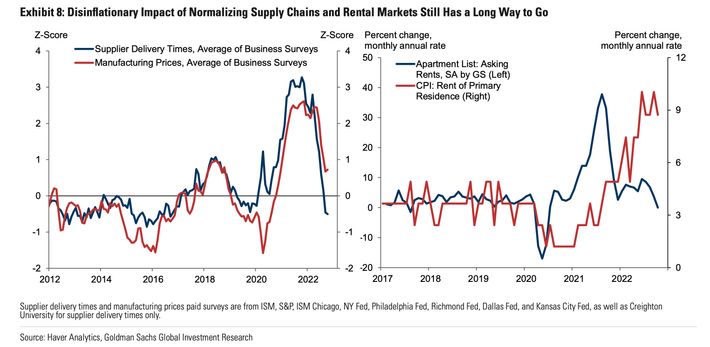

While bears focus on structural impediments to supply growth, bulls take heart from near-term trends. Goldman Sachs argues that various markets are finally recovering from pandemic-induced shocks to supply availability. When the COVID crisis rendered all manner of in-person services either unavailable (due to shutdowns) or undesirable (due to infection risk), consumers across the developed world cut back on purchases of yoga classes, theater tickets, and vacations and ramped up their spending on deliverable goods. This naturally overwhelmed various supply chains — from shipping to trucking to semiconductors. But now, as Goldman notes, consumers are rotating their spending away from goods and toward services. And although this puts pressure on service-sector prices, the rebalancing nevertheless reduces mismatches between demand and supply and, thus, inflation.

In addition to spiking demand for manufactured goods, the pandemic triggered a real-estate boom. As affluent consumers found themselves spending more work and leisure time at home, they began craving more square feet. Like the surge in goods demand, though, this was a one-time shock. Now that the pandemic is easing, and rates of remote work are falling and pressure on the rental market is easing. The pace of rent increases in new leases has fallen sharply since mid-2021.

As Alex Williams of Employ America notes, this deceleration in rental prices began before the Federal Reserve’s rate hikes should have had any discernible impact on the rental market. Thus, it seems like the sector is actually disinflating on its own — as one would expect if the 2020 to 2021 surge in rents were a product of a one-time spike in demand. This hypothesis is consistent with the extraordinary outflow of migrants from urban centers during the pandemic: As households sought more space in lower-cost suburban areas, rental prices in those places shot up faster than rents in the urban centers fell (since there was a sizeable population of would-be New Yorkers, San Franciscans, etc. ready to move into those cities once housing there became just a little a bit more affordable).

In Goldman’s account, these disinflationary pressures will enable the Fed to bring down prices without crashing the economy. The central bank will nevertheless continue raising rates, thereby weakening the labor market. But this will increase the U.S. unemployment rate by a mere 0.5 percentage points to just over 4 percent, thanks in part to the peculiar form that labor market “overheating” took in the past two years.

In previous inflationary periods, excess demand for workers manifested in ultralow unemployment. But during the post-COVID boom, excess demand showed up in an extraordinarily large gap between job openings and applicants. In Goldman’s calculations, that gap between listings and workers peaked at nearly 6 million. When economic conditions worsen, firms generally cut the hiring of open positions before they cut existing staff. Thus, those excess job openings serve as a cushion against mass layoffs: The Fed’s hikes need to rip through those prospective jobs before they cut deeply into actual payrolls. The jobs-workers gap has already fallen to just over 4 million. But that still provides the labor force with a substantial layer of protection against declining demand.

Of course, falling job openings still hurt workers. And for the already unemployed, it means contracting job opportunities. But the elimination of potential jobs does not reduce consumers’ purchasing power quite as much as the elimination of existing ones.

At present, real disposable income is rebounding from earlier in the year, when soaring inflation and declining government spending took a toll on household balance sheets. And since Goldman does not expect the Fed to engineer a recession, the bank anticipates that real disposable income will be rising significantly by the end of 2023.

In sum, the disinflationary impact of post-pandemic normalization will make it easier for the Fed to bring down inflation without gutting the labor market while resilient consumer strength will keep the economy out of recession in early 2023 and accelerate growth by year’s end.

Goldman doesn’t offer a rosy rebuttal to BlackRock’s projections of long-term structural economic liabilities. And I won’t detail one here. But it’s worth noting that just a few short years ago, many economists believed that the world was trapped in a near-permanent state of weak demand and structurally low inflation — since aging populations reduce demand for consumer durables, spending was increasingly being directed toward digital goods with low marginal costs of production, and automation and artificial intelligence promised to increase productivity. Furthermore, if the green transition threatens energy shocks in the near term, it should ultimately dramatically reduce electricity and fuel costs.

Ultimately, our economic future is radically uncertain. As COVID illustrated, unpredictable shocks can remake our material lives in a matter of weeks. And as recent advances in AI and fusion energy illustrate, technological advances can rapidly transform the nature of our economic problems. Next year, the U.S. economy will almost certainly slow down. Maybe by a lot. Hopefully by a little. Beyond that, it’s probably best to do as Goldman, BlackRock, and Vanguard all advise — hedge your bets.