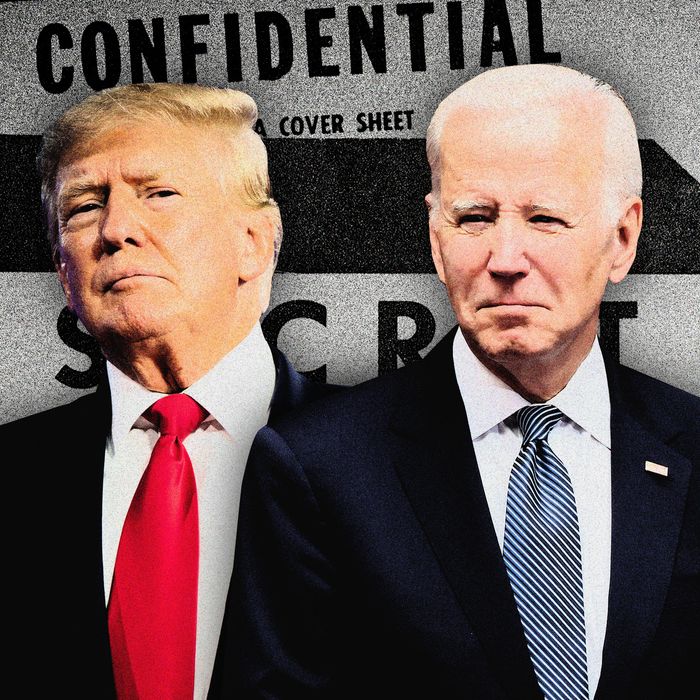

In the nearly half-year since the FBI searched Donald Trump’s home at Mar-a-Lago and retrieved a cache of classified documents, I have returned on more than one occasion to a couple of conversations that I had with two friends and former federal prosecutors in the weeks following the search. Those conversations came rushing back to me this week, and again yesterday, when Attorney General Merrick Garland announced the appointment of a special counsel to investigate President Joe Biden’s retention of classified documents following his tenure as vice-president in the Obama administration.

One of those friends was a former line prosecutor who had investigated cases involving classified information, and the other was a well-respected veteran and former senior official in a marquee U.S. Attorney’s office. Both detest Trump as a politician and human. At the time, many people in the media were ready (once again) to see Trump hauled off to prison, and although the two of them came from very different professional perspectives, they converged on the same point — that a so-called “documents case,” as one of them put it, was not serious enough to warrant the first-ever criminal prosecution of a former president.

That position is debatable, to be sure, but you can shore it up with a few points that are now relevant to not just Trump, but Biden as well. One is that the federal government routinely overclassifies things, at least at the lower levels. (Trump and Biden apparently both had documents marked at the highest level of classification, where this rule of thumb is much less potent.) Another is that a document can be marked classified if only a small portion of it concerns classified information, even if that information is not particularly sensitive or informative in isolation.

The management of classified documents is also a perennial Washington problem that has drawn in prominent figures of both parties, and there is a free-floating sense among many former federal prosecutors that if you are going to prosecute a former president, it should be for an undeniably serious and easily understandable offense — like, say, attempting to unlawfully stay in power or committing financial fraud — both as a matter of political Realpolitik and to maximize the odds of a conviction before a jury whose members will be well acquainted with the defendant.

You don’t have to take my word for this: Late last year, NBC News published a story that quoted an anonymous “former U.S. Attorney, a Trump critic,” who “said a mere documents-mishandling case is not serious enough to merit charging a former president, unless prosecutors can prove aggravating factors such as intent to share the material, or obstruction of justice.” The fact that this “Trump critic” would not attach his or her name to the claim was a nice flourish — a reflection, perhaps, of the fact that saying this publicly might not go over well with the many people who want Trump in a federal penitentiary.

Trump, of course, may have obstructed justice, as the Justice Department has argued, particularly in light of the months of stonewalling and apparent lying to federal investigators about whether he had returned everything in his possession. That is one of several potential but important points of difference between his case and that involving Biden — as well as the apparently much smaller volume of documents (at least as of now) that is associated with Biden. His lawyers, by contrast, appear to have voluntarily searched and voluntarily disclosed the discovery of the documents to the Justice Department, which appears consistent with Biden’s claim that this was all inadvertent and occurred without his knowledge — a proposition that will apparently now be tested by the newly appointed special counsel.

Here is another important difference that has largely been lost in the coverage this week: Under DOJ policy, Biden cannot be indicted while he is the sitting president.

You may have a vague recollection of this fact because it controlled the outcome of Robert Mueller’s Trump-Russia investigation all the way back in the distant past that was 2019, but it is newly relevant and may complicate Garland’s path forward. The most that the newly appointed special counsel can do, even if the facts somehow get much worse, is write a nasty report about Biden, as Mueller himself did with Trump, but as long as Biden is in office, the Justice Department will not be charging him with anything.

That means that the most powerful legal sanction that the Justice Department can impose against Trump is unavailable for Biden. That is a potentially serious wrinkle for an attorney general who has been fond of saying (again and again and again, in different variations) that “the essence of the rule of law is that like cases are treated alike. That there not be one rule for Democrats, and another for Republicans, one rule for friends, another for foes, one rule for the powerful, another for the powerless.”

Some people have interpreted these sorts of comments from Garland as akin to saying that no one is above the law — that if you commit a crime, the federal government should charge you with it. It is better read as a principle of equal treatment, which may mean treating two potential defendants equally harshly or equally leniently depending on the facts, law, and surrounding circumstances.

It is very possible that this view of the law and its proper application will eventually weigh, perhaps even dispositively for Garland, against charging Trump in connection with the hundreds of documents he retrieved and withheld and then apparently lied to investigators about. When you throw in the fact that many federal prosecutors appear not to think much of these sorts of cases, the atmosphere for Trump seems to be improving. In a supremely bizarre turn of events, this would mean that Trump might once again end up being the beneficiary of the Justice Department’s policy against indicting a sitting president, at least in this particular area. (The revelations this week should have no effect, legally or logically, on any criminal charges pertaining to Trump’s monthslong campaign to prevent Biden from taking office.)

Many members of the public who have earnestly followed the events since the search of Mar-a-Lago are now likely to get better educated about some of the complexities — and the importance of the open questions — surrounding Trump’s conduct. It is not the case, and was never the case, that “a documents charge, as presidential accusations go, would be relatively easy to prove,” or that it would be similar to “straightforward crimes” that prosecutors routinely charge, like “bank robbery and narcotics trafficking.”

The fact remains, for both Trump and now Biden, that we do not know the most important fact either legally or politically: What was actually in all of these documents?

To be sure, there have been Trump-unfriendly leaks on this subject, but the reality is that we know almost nothing concrete about what was actually in the material he held, which could make the facts far worse or far better for him depending on the answer. If, at one end of the spectrum, he had a bunch of isolated pieces of otherwise useless sensitive information, that would not be a particularly compelling case — but if he had, say, a bunch of documents that thoroughly detailed how the U.S. government might destroy Iranian nuclear capabilities, that would be another thing entirely. The same thing applies to Biden, which is why the literal talking points circulating among Democrats this week that have been parroted by so many people in the media in Biden’s defense in recent days are not as dispositive as they think (or at least claim).

None of this requires you to be an idiot. Trump is a terrible person who frequently does awful and possibly illegal things on purpose. Biden is nothing like him in that respect, and inadvertently holding onto a small number of classified documents, if that is what happened, would be entirely consistent with his slightly bumbling and absent-minded affect — one that is often charming but sometimes, and in this instance, is infuriating for the way in which it can needlessly create political headaches and controversy.

For now, we find ourselves in truly uncharted terrain. It was already historically unprecedented for there to be legitimate questions about whether the Justice Department might criminally charge a former president — something that has never happened in this country. We now have a situation in which the current president is also simultaneously under criminal investigation, and for conduct that is at least superficially similar.

It is a stunning turn of events and an undeniable gift to Trump — a man who seems so easily to slip in and out of the grasp of prosecutors.