The National Book Awards are the Oscars of the publishing industry, although nobody who attended the ceremony on November 16 at Cipriani Wall Street would likely confuse the two. Still, it wasn’t without its glamour and drama. That night, Padma Lakshmi, best-selling author and former wife of Salman Rushdie — who only a few months before had been nearly murdered for his writing — was the host. Her yellow strapless dress was conspicuously adorned with a union button in solidarity with the striking HarperCollins staffers picketing out on the sidewalk. But all eyes were on Markus Dohle, the tuxedo-clad CEO of Penguin Random House who had for 14 years been the most powerful and successful publishing warlord in the room.

PRH had become the biggest publisher in the game after a 2013 merger, led by Dohle, that saw Random House gobble up Penguin. The combined company had cast a long shadow over its four smaller rivals — Hachette, Macmillan, HarperCollins, and Simon & Schuster — but Dohle wanted more and had spent much of the past two years fighting to buy S&S in order to create a world-spanning leviathan.

Few in the room had wanted the $2.175 billion S&S merger to happen. Already most felt that PRH had become too bureaucratic, too unwieldy, and they worried that competition among book buyers would be hobbled further if it went through. Many had cheered on the antitrust hawks of President Biden’s Department of Justice who sued to block the deal’s consummation. After a bruising, and in some ways humiliating, trial, Dohle had been denied his ambitions by the court. But more importantly, in the process, his imperial publishing house’s weaknesses had been laid bare for all to see.

“People were trying to decide if they still needed to kiss the ring,” recalls one top executive who was at the dinner that night, “or if there was even a ring left to kiss.”

Though Dohle had declared his intention to appeal the court’s decision, it was looking like a long shot, and Cipriani was humming with Schadenfreude. And then, sure enough, come Monday, the deal was officially pronounced dead after S&S was yanked off the table by its parent company, Paramount. Three weeks later, on December 9, Dohle resigned.

Whether the demolition of the S&S deal was going to be good or bad for the actual making of books remains another question entirely. And whoever does end up getting S&S — it’s back on the market — won’t be as well known or as well liked as Dohle.

“He brought an optimism and energy to the business during fragile moments,” said book agent and Dohle pal Elyse Cheney, “but, you know, the last year and a half has been very tough.” Paul Bogaards, the well-known book publicist who worked for 32 years at Knopf (which is part of PRH) before striking out on his own, told me that “many of the suits in publishing are tone-deaf to the needs and wants of the people who help make the business run. Markus has had a great, historic career in publishing. But he failed to read the room when it came to the merger.”

Random House, the most storied of American publishing houses, had been acquired by the German media conglomerate Bertelsmann in 1998 and merged with Bantam Doubleday Dell. It was the era of corporate consolidation in books, accompanied by much grumbling at the time about the perceived lack of competition and a fear of a creeping cultural blandness. Still, publishing adapted.

In 2008, Bertelsmann put Dohle in charge of Random House. Nobody was quite sure what to make of him. Markets were tanking and people were declaring the end of print. (Remember that brave new world of Kindles and Nooks?) Dohle, then 39, was not a book editor. He had trained as an engineer and had been running Bertelsmann’s highly profitable printing division, which was so far from any sort of glamour that it was nicknamed “Siberia” within Bertelsmann.

But he soon proved to have an intuitive understanding of the business, and his mechanical background allowed him to grow out a muscular distribution infrastructure that became the envy of other publishers. He counterintuitively championed the physical book. And once he achieved the 2013 deal that combined Random House with Penguin, he found himself ruling over a global juggernaut with 11 branch CEOs reporting to him from midtown to Madrid. He became the figurehead of the industry, and he turned out to be a larger-than-life character in a contracting industry that had been wanting for them. Even the most jaded New York editor found it hard not to be at least a little charmed. “He’s like our Arnold Schwarzenegger,” said one.

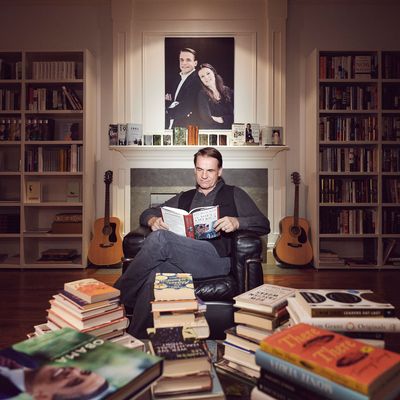

Dohle, now 54, grew into the job. His house is up in Scarsdale, but he would make it a point to drop in on book parties around the city. He sat on the board of PEN America alongside Masha Gessen and Jennifer Egan, became tight with Dan Brown and Andrew Solomon, and personally negotiated Barack Obama’s book deal.

The guy had banked a lot of goodwill. But before long, there were whispers that Dohle had made PRH so big that it was inefficient. It was losing market share to more nimble competitors. When Paramount put S&S on the market — a book publisher doesn’t exactly fit into a corporate vision predicated on streaming services — Dohle seemed to see a potential merger as a way to make up for market-share loss through brute-force consolidation.

After announcing his intent to buy S&S, things started to go wrong for him straightaway. Organizations such as the American Booksellers Association that ordinarily have good relationships with PRH generally and Dohle personally began publicly trashing the merger. On the eve of the trial, the president of the Authors Guild, Douglas Preston, wrote an op-ed in the Los Angeles Times slamming the merger.

All of which might not have mattered much except that the regulatory environment had changed drastically. Dohle’s 2013 merger got by Obama’s people with no problem, and when Dohle announced the S&S deal in November 2020, he had little to fear from the Donald Trump appointees who were then running the DOJ; they had already approved much larger deals, such as Disney’s purchase of 21st Century Fox (although they did try to block the AT&T–Time Warner merger, many observers thought that was less out of principle than political spite over CNN’s coverage, and in the end, the courts let the ultimately misbegotten merger happen).*

But then Joe Biden brought antitrust warriors to power again for the first time in decades. He appointed consolidation skeptic Lina Khan to run the FTC and nominated Jonathan Kanter to lead the DOJ’s antitrust division. Newly in the job, Kanter had a juicy merger before him. It was just the sort of high-profile deal with which he could flex some monopsony-busting muscle.

The DOJ sued to block the deal, arguing that the big five being reduced to a big four would leave too much buying power in the hands of too few, screwing over authors. (PRH, ready to defend the deal, hired the same legal team that had successfully shepherded the AT&T and TimeWarner merger to completion.) The case was handled by Judge Florence Y. Pan, a Biden appointee; this would be the first case in her new role.

The trial finally began in August 2022. It lasted only three weeks, but for Dohle it was about as long and unhappy as Jarndyce v. Jarndyce. The DOJ hinged its case around a tiny sliver of top book deals — the kind that pretty much only the big five can compete on — to show how concentrated power in publishing already is. “Freelance writer” Stephen King took the stand to support the government’s point.

Dohle and his executives were made to explain a lot about how PRH had been operating since the 2013 merger.

Like the other publishing houses, PRH consists of many imprints, each with its own flavor and identity. The imprints are grouped into divisions. (PRH is so dense it consists of 94 imprints — 37 being children’s imprints — spread across seven divisions.) The different divisions operate like separate companies, even though they’re all plugged in to the same corporate infrastructure, jockeying for resources. The main three divisions within PRH are Penguin Publishing Group (imprints include Riverhead, Penguin Classic, Viking, etc.); Random House (its got Ballantine Books, Bantam, Crown Trade, etc.), and the vaunted Knopf Doubleday Group (Alfred A. Knopf, Doubleday, and Pantheon, among others).

The imprints compete for book deals against one another, even if they’re part of the same division. That keeps things hot and competitive and individualistic and creative. Supposedly.

But then the trial revealed that all the different tentacles within PRH were being tangled up to create some kind of publishing kraken. Madeline McIntosh, the CEO whom Dohle had appointed to run the U.S. operation, started to encourage the separate divisions inside PRH to get on the same page while competing against one another for the same book at auction. There was a 2018 document, written by McIntosh, that talked about “increased background coordination in auctions to leverage internal demand information better and avoid internal upbidding.” Such a practice might sound simply like how a corporation would work to you, but book publishing thinks of itself as being on a sort of genteel old-school honor-system version of capitalism. This division coordination that McIntosh was torquing up inside PRH posed a couple of problems.

The first and most immediate was that the government pointed to McIntosh’s documents and emails as evidence of PRH’s true behavior and the leverage it wields. The second problem was that it scandalized the book agents. Like Hollywood, book publishing is a business built on relationships with editors and agents working together for years. The agents have always operated under the good-faith agreement with the publishers that, while some imprints in the same division can get to talking during an auction, the separate divisions were basically never to collude, which they had started to do inside PRH. If that were to become a habit, it could lead to a lot of lowball offers.

I asked David Kuhn, co-CEO of the literary agency Aevitas Creative Management, about the coordination discussed at the trial. “I was always under the impression that there was a Chinese wall between divisions within PRH as they prepared bids for an auction,” he said. “I was aware that imprints within those divisions discussed what they planned to bid, often deciding to make a ‘house bid’ that represented more than one imprint. But the fact that this was happening at the division level was a surprise and not a welcome one.”

Dohle had understood how sensitive the agents were to this. That’s why, shortly after he announced his intent to buy S&S, he sent them all a letter promising that, should the deal go through, the combined S&S and PRH wouldn’t be secretly in cahoots at auction. “We believe that allowing S&S to continue to bid independently will further enhance our ability to find, compete for, and publish the best books,” he wrote to them. But then, that was supposed to be the story inside PRH, too. The agents were starting to feel burned.

Curiously, sources say Dohle was similarly unaware of the level of in-house coordination that McIntosh was overseeing at PRH and that he learned of it for the first time in the run-up to the trial. It seems a little unlikely that he wouldn’t know how the pricier deals inside his most important branch were being put together. But then the handful of deals the DOJ magnified were the exception, not the rule, so it’s plausible Dohle wouldn’t have been privy to them. Especially since he only has to get called in for approval on deals that exceed $2 million. (For example, he signed off on the Obama deal, which was reported by the Financial Times to be worth $65 million.)

“The government uncovered a lot of data and practices through discovery across the industry,” noted Michael Cader, founder of the trade website Publishers Lunch, which had put out the definitive account of the saga — a 1,188-page, 6.5-pound $100 doorstop called The Trial. “There was a lot of interesting information revealed about how dealmaking worked at the highest levels,” he said.

The agent issue was the microproblem. The macroproblem was that PRH was perhaps already too big for it’s own good. Back in the day, when each house was smaller, the imprints and divisions beefed among one another more than was probably helpful. A little corporate lubricant helped — it sure was nice to have access to all those warehouses and resources that Dohle built — but how much was too much? Somewhere along the way, the bureaucrats inside PRH began gumming up the works with all their restructurings and imprint-impinging.

“Part of the unusual dance of the whole acquisition was that, for years, Penguin Random House told us how well the merger with Penguin had worked out,” said Cader, but it turned out they were “stalled.” A renowned editor at a rival house says, “The trial forced PRH, almost against their will, to reveal what we all knew, which is that it’s already too big, and if you added S&S, it would be way too big, a behemoth that would make the whole publishing industry seem out of whack.” Several other sources happened to use the same exact adjective when I asked them to describe the trouble with PRH: “unwieldy.”

From the perspective of an editor, the promise of working for PRH has always been the might of its sales department and relationships with booksellers; theoretically, all the clout that a colossus affords can translate to better visibility for the books you’re championing. But when a house becomes so big, with so many books produced, a centralized sales team must pick and choose which titles get the institutional push. The ones that end up getting marketing and publicity resources are often safe bets — the celebrity memoirs or formulaic follow-ups from proven authors. This corporate culture has chafed against creative editors, the people who got into the business with romantic notions of discovering new writers and sticking with them even if their first couple books bomb, BookScan be damned.

“We have agents approaching us with books they feel will get lost in the juggernaut of a big-five house and will get better care, and be published better, at a smaller house,” said Cindy Spiegel. She and her fellow editor Julie Grau had run the Spiegel & Grau imprint inside PRH — they’d published hits including Piper Kerman’s Orange Is the New Black and Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me — until it was folded during a reorganization in 2019. (They’ve since relaunched independently.)

Insiders at PRH tell me things have become too homogenous and “rule-by-committee.” The Knopf division within PRH was the last fiercely autonomous fiefdom, since it always had the protection of Sonny Mehta. It was a bit like how David Remnick’s New Yorker is the last remaining inch of Condé Nast not under Anna Wintour’s heel. But Mehta died in late 2019, and with him went the last of the visionary, all-powerful editor-in-chief model. The suits have been clawing back power from the imprint sachems for a while now, and their decisions seem, to many an editor, entirely data-based and a bit short-sighted. (Good luck trying to get the suits to approve cheap Champagne for your office party or a paperback reprinting for your underselling author.)

It’s clear from the trial that Dohle was similarly worried about this management morass. He was asked directly if PRH “has too many layers of management in acquiring books.” He answered, “Yes.” In some of his correspondences that were exhibited, Dohle expressed frustration about operations inside the U.S. house and seemed to blame McIntosh and one of her key lieutenants, Gina Centrello, who runs the Random House division within PRH. “It’s really poor what happened,” Dohle wrote in one text to colleagues while discussing how “we really screwed it on the product side post-merger” and “the risk that MMC and Gina created for us.”

McIntosh, an art-history major who lives in the Dakota, is married to the thriller novelist Chris Pavone. She was earlier than most in understanding new media and the direction the business was headed. In 2008, the year Dohle took over at Random House, she jumped over to Amazon for 18 months, working in Luxembourg as the director of content acquisition for the international launch of the Kindle. Dohle wooed her back, eventually putting her in charge of the whole U.S. shop. She is said to be as inscrutable and cerebral as he is loquacious and back-slapping. “Stylistically, they could not be more different,” says one person who has worked closely with both. “He’s probably too freewheeling, and she’s too clamped down.”

The management tussle on display in the trial posed a quandary: If Dohle was agitated that his U.S. operation was being run like a super-quango, then why did he think the solution was to buy another big company to throw on top of it? The merger might have been a $2 billion Band-Aid that stemmed market-share loss, but it most certainly would have exacerbated the unwieldiness of the house.

One thing is for sure: Now that PRH knows it can’t simply purchase any more of the competition, it must look inward. This week, it’s riding high with Prince Harry’s book, and next month it’ll have Rushdie’s new novel, which is likely to be a smash. But the leadership learned from the trial that more power must be returned to the imprints.

It’s not like Dohle will disappear. Bertelsmann is calling him an “adviser” to PRH. And for now, he still sits on the board of several industry bodies, including PEN America and the National Book Foundation. His closest deputy, chief operations officer Nihar Malaviya, is acting as interim CEO. I’m told he is getting the job on a permanent basis, even as some in New York are already questioning if Malaviya has the editorial gravitas to fill the void left by Dohle. But then that’s what they said about Dohle in the beginning, too.

Already, changes are afoot. They’re talking now about which management strictures ought to be unraveled. Apparently one of the subjects very much under review is the extent of in-house coordination at auction. And this morning, Centrello is set to announce her retirement. McIntosh and Malaviya intend to leave that powerful division-chief job vacant, which is one way to eliminate a bureaucratic bottleneck inside the house, even if it raises other questions about how the new org chart will work.

After Judge Pan blocked the deal and Paramount declined Dohle’s wish to appeal, Bertelsmann had to pay a $200 million termination fee. Which is a nice cushion for Paramount while it considers its options for S&S.

They still wish to unload it. In her ruling, Judge Pan said that another publisher was “likely” to “prevail in a future sale,” since no one else is as big as PRH. But after what they were put through publicly, who would dare try?

Vivendi, the French media conglomerate, is believed to be the most likely next suitor for S&S. But if so, that won’t happen for a little while because Vivendi is currently trapped in its own merger hell back in France, where the European Commission is ruling on its takeover attempt of Legardère, which owns Hachette. The commission isn’t expected to hand down a decision until May. (There is also the side point that Vivendi has been the media mouthpiece of right-wing owner Vincent Bolloré — his son is supposedly taking the reins — which might not go down well in a culture where S&S’s employees threw a temper tantrum when their company published Mike Pence.)

The other seemingly likely option for S&S is even less appealing. The bankers servicing Paramount have been calling around, and many people think the publisher could be picked off by private equity. Employees inside the house describe this to me as their nightmare scenario. Emails between S&S CEO Jonathan Karp and an exec at Paramount referenced at trial showed Karp’s belief that a financial buyer could end up being “better for the employees of S&S, and arguably the larger book-publishing ecosystem.” (His argument seemed to be that mergers between two publishers often result in layoffs of many redundant positions.) But the Banquo’s ghost that haunts that proposition is Houghton Mifflin Harcourt; that publisher lost much of its prestige and reputation after it fell into the hands of the money people. As the agent Andrew Wylie said at trial, S&S ought “to have its enterprise supported by an understanding parent company.”

So was Dohle right about PRH being the best possible home for S&S after all? Dohle, the engineer turned champion of free speech and literature, had made his liberal politics clear, marching in the streets with Salman Rushdie after Trump was elected. Should S&S end up in the pocket of private equity, only to be McKinsey’d to death, well, all that sanctimony about Big Book Getting Too Big might sound awfully regrettable in retrospect. Meanwhile, S&S remains a well-run business: Its valuation has only jumped higher and higher since he first tried to buy it back in 2020. Atria, an S&S imprint, has the rights to those Colleen Hoover novels currently rocking the best-seller lists. S&S has also got Jennette McCurdy, Jerry Seinfeld, and Bob Dylan. It’s a lean operation with a string of hits.

Still, the epic Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster trial seemed to have marked the last of an era. “I think this may be, on some level, the end of the love for conglomerate publishing,” mused one publishing pooh-bah. “This is a 30-year-long story that we’re watching end.”

*Correction: An earlier version of this piece incorrectly stated that the Trump DOJ approved the AT&T–Time Warner merger.