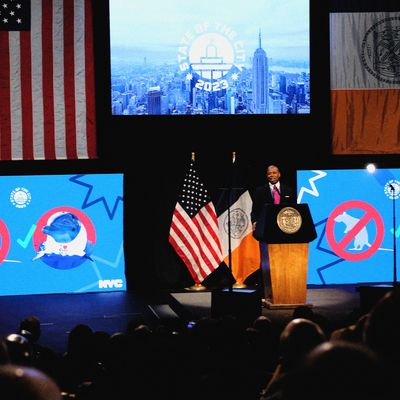

Eric Adams begins his second year in office on a mission to make the mundane machinery of municipal government look sexy. New York’s mayor kicked off his recent State of the City address with a fancy Broadway-style production at the Queens Theatre complete with dancers, singers, and a highly produced highlight video played to a cheering, handpicked audience of supporters.

But behind the showbiz flashiness, Adams focused on bread-and-butter issues he called “the four pillars that uphold a strong and sustainable society: jobs, safety, housing, and care.” The mayor ticked off a laundry list of decidedly unflashy promises that included expanding job-training programs, launching a citywide composting program, converting Uber and Lyft cars into an all-electric fleet, providing health screenings to people in the city’s homeless shelters, and making zoning changes to turn half-empty Manhattan commercial towers into apartment buildings.

“Don’t let it fool you,” he told the crowd. “I may wear nice suits, but I’m a blue-collar cat.”

It’s not easy to follow the stream of promises Adams makes. There are lots of numbers and lots of plans. On the jobs front, for instance, the mayor said, “We will connect 30,000 New Yorkers to apprenticeships by 2030.” He pointed to a previously announced science hub in Kips Bay that he says will create 10,000 jobs. And given the shortage of nurses, said Adams, “we will support 30,000 current and aspiring nurses over the next five years with everything from additional training to mentorship and clinical placements.” Changes in contracting procedures, he said, “would allow us to keep 36,000 economically disadvantaged workers connected to good jobs every year. “

That sounds great until you consider that 30,000 or even 100,000 jobs — in a city with more than 4 million private-sector jobs — makes only a dent in the city’s 5.3 percent unemployment rate. And the jobs don’t appear instantly. Those 10,000 science-hub jobs are estimated to be created over a 30-year period, and the 30,000 nursing jobs will come online over five years. This is in a city that added a total 200,000 jobs in the last year alone.

Adams’s grind-it-out approach stands in stark contrast to Mayor Michael Bloomberg’s equivalent State of the City speech delivered almost exactly 20 years ago in January 2003. Bloomberg, who’d spent much of his first year winning control of the school system and dealing with the aftermath of the destruction of the World Trade Center, used the speech to announce a number of megaprojects — including the launch of the 311 phone system for nonemergency calls (which has become the front door of citizen interactions with city government), the merger of the Departments of Correction and Probation, and his intention to extend the subway system to the far West Side.

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s first State of the City painted a portrait of big things to come. De Blasio vowed to combat economic inequality by demanding a higher minimum wage, chastised “slumlords,” and announced that the city would provide legal services to tenants who were treated unfairly. De Blasio included a promise that the administration would build an independent interborough ferry system and announced an audacious plan for a city-within-a-city of as many as 11,250 affordable apartments by decking over the 180-acre Sunnyside Yards in Queens.

The Sunnyside proposal never came about, but many of Bloomberg’s and de Blasio’s bold promises — such as Bloomberg’s extension of the 7 train, which made Hudson Yards possible, and de Blasio’s ferry system — have transformed the city.

By contrast, I told Adams, the new administration seems focused on small-bore initiatives.

He disagreed. “It is not small items. It is items, when you do them upstream, that don’t turn into big items downstream,” he told me. “People often ask, ‘What is your signature issue like pre-K?’ It’s dyslexia screening. Thirty percent to 40 percent of our inmates are dyslexic in jail. Eighty percent don’t have a high-school diploma or equivalency diploma. So it seems like small items, but they’re not. These are the major feeders to the crises that we face.”

Fair enough. We should all want City Hall to make small, smart investments of time and effort that result in big payoffs down the road. And as Adams pointed out, creating what will be the largest composting program in the U.S. is no small feat.

“Our composting program, 13 million pounds of waste that we are taking out of our sites into where we dump our garbage. That’s an amazing accomplishment — and that’s for only a three-month period,” he said. Ditto for the agreement Adams says the administration has struck with Uber and Lyft to make their fleets — about 100,000 vehicles, according to the mayor — emission-free by 2030.

The year-one verdict on Adams’s signature issue, public safety, is mixed. The most serious crime, murder, dropped 11 percent last year. The 433 homicides in 2022 marked the lowest figure since 2019, meaning the spike in killings that New York saw during the pandemic has receded. Shootings declined by 17 percent and briefly all but vanished from the Bronx, which in October saw its lowest one-month number of shootings (13) since the 1990s.

More good news: An enforcement effort in the subways launched in October led to a 43 percent increase in arrests and a steep drop in crime underground. Adams’s theory is that pressing hard on the most serious crimes will inevitably bring down overall violence. The idea is getting a rigorous test: Last year saw 4,627 arrests for gun possession — the highest number in 27 years.

But a surge in robberies and burglaries has much of the city on edge, and it’s not clear whether the measurable progress in stopping murders and shootings has registered with the public. The latest Quinnipiac poll, taken after the State of the City speech, shows crime to be by far the most pressing issue New York voters are worried about — more than affordable housing, schools, inflation, and COVID combined.

Adams has no intention of letting up in the battle against criminal violence. “I’m not going to be happy until we don’t have any crimes, particularly felony crimes” in the subways, he told me. “We have an average of six felony crimes a day with 3.9 million riders. We want to get down to zero. I want New Yorkers to know that we are going to do everything that’s possible to accomplish that. That’s when we are happy. That’s when we can spike the ball.”

A coming cash crunch for the city is not anything he can speak about in grand and ambitious terms, but right now it is at the top of his inbox. Revenue to the city is falling as federal pandemic aid dries up and as tax revenue from commercial real estate (and the businesses that once occupied those units) continues to plunge.

While all city agencies were asked to submit 3 percent in budget reductions during this budget year and 4.75 percent next year, the NYPD only identified 1.3 percent in cuts — and is likely to run up a significant overtime bill. In fiscal year 2022, the agency spent significantly beyond its $513 million overtime budget ($777.9 million). A similar overrun could add significantly to the $5.3 billion Adams has budgeted for the NYPD.

Overall, the budget cuts won’t sit well with members of the City Council, who are already hearing from families concerned about expected cuts to libraries, schools, and other popular needs. Looming over all of the budget questions is the cost of housing migrants, which Adams says could easily top $2 billion.

The mayor’s flexible operating style — “pivot and shift,” he says frequently — amounts to some painful, unpopular moves. Several of those choices are being made outside of the public eye — such as City Hall’s directive calling on agencies to achieve budget savings by attrition, allowing some positions to remain unfilled.

In early December, a report by Comptroller Brad Lander noted with a degree of alarm that several agencies have dozens or even hundreds of unfilled positions — from the Department of Buildings and the Parks Department (both showing more than 30 percent of jobs vacant) to the Human Rights Commission (63 percent vacant). In a different report, Lander warned Adams’s budget director about asking agencies to leave positions open as a cost-saving measure: “We urge caution in applying such a blunt instrument to the positions that keep the City functioning … eliminating currently vacant positions reduces head count but does not take into account whether mission-critical services are adequately staffed.”

Jumaane Williams, the public advocate, signaled concern over the risk of allowing the city’s workforce to shrink too much. “We have been a part of the call saying that some of these lines have to be filled up — inspectors in the Department of Buildings, inspectors in Housing Preservation and Development saying that we can’t get the job done,” Williams told me. “We want to make sure that we are not moving into austerity cut times, because that does have an impact on the public safety and health of the entire city.”

It could be that Adams’s practical plans, shorn of big, expensive projects, are exactly what the city needs at a time when money is getting tight. But Williams warns that the strategy has limits. “There was a line I’ll never forget in The Wire, and it was that nobody does more with less,” he told me. “Everybody does less with less.”