Quick: Can you name any secretaries of Transportation prior to Pete Buttigieg?

It’s possible you’ve heard of Buttigieg’s predecessor, Elaine Chao, as she resigned from Donald Trump’s administration the morning after January 6 and is married to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell. Old-timers may remember another secretary of Transportation with a famous senatorial spouse, Elizabeth Dole, who later ran for president herself. By and large, though, running USDOT has generally been considered a second-tier Cabinet post for competent but undazzling politicians whose greatest ambition was to someday have an airport named after them (like San Jose’s Norman Y. Mineta).

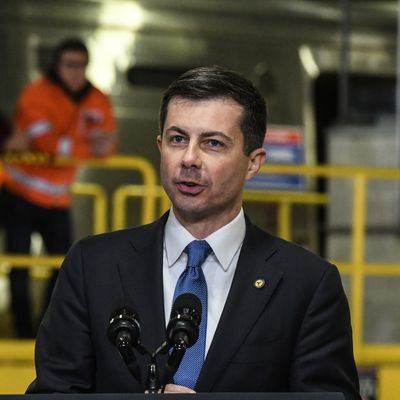

But when Joe Biden named the former South Bend mayor and 2020 supernova to the post, ears perked up. Mayor Pete had a national fan base left over from his impressive, if unsuccessful, presidential run. He also had a lot of critics, ranging from progressives who saw the former McKinsey & Company consultant as a product of technocratic neoliberalism to conservatives offended by his identity as an avowedly Christian gay married man. Plus, the Beltway commentariat couldn’t stop speculating about Buttigieg replacing Kamala Harris in 2024 or supplanting her as Biden’s successor in 2028.

Transportation secretary initially seemed like a dream job for a politician seeking to prove he could do more than run a small city in deep-red Indiana (though it was reported that Buttigieg had initially yearned to be ambassador to the United Nations). The focus on Buttigieg and his department only intensified with the passage of the 2021 infrastructure package. As Ross Barkan noted at the time, it looked momentarily as though Mayor Pete was in the catbird seat:

In a year of woe and confusion for Biden … it has been Buttigieg who is out front and unruffled, the public face of a trillion-dollar infrastructure package that might be the president’s defining domestic-legacy item …

Democratic politicians still bristling from the Trump years, when the penny-pinching Elaine Chao ran the department, sing hosannas for Secretary Pete. “My God, it’s night and day,” says New Jersey governor Phil Murphy. “He’s a guy who understands what it’s like being chief executive. If you’re a governor, you’re automatically on a similar wavelength with him. He’s lived in my shoes, and to some extent, I’ve lived in his.”

And when word got out in mid-2022 that Buttigieg had relocated to Michigan, tongues really started wagging. Ostensibly, he just wanted to move his growing family closer to his husband Chasten’s parents. But Michigan also happened to be a red-hot battleground state where an ambitious Democrat might soon have a chance to run for governor or the U.S. Senate.

Today, however, Buttigieg’s Transportation gig is looking less like a dream and more like a nightmare. It has turned out to be a complicated job made even harder by the glare of publicity Buttigieg has attracted. He faced criticism for excessive coziness with the auto industry. He was forced to pick sides in a lot of long-standing transportation policy disputes that could change how people live and work. And he has been front and center in several transportation-related crises, including the supply-chain crisis and repeated breakdowns in airline travel.

The airline woes may have been the most damaging. While the industry is a very small part of USDOT’s portfolio, it became a huge focus in 2022 when serial waves of flight cancellations stranded passengers who were already frustrated by high fares and poor customer service. And beyond the industry’s own problems, chronic issues at the Federal Aviation Administration, which is part of USDOT, have burst into public view. When a breakdown of an FAA safety-warning system grounded thousands of flights last month, it overshadowed anything Buttigieg has done on electric vehicles or bridge repairs.

Reviews of Buttigieg’s performance as secretary of Transportation aren’t uniformly negative. The general consensus is that he was a fine lobbyist for the bipartisan infrastructure bill, and he has promoted its implementation effectively. He can’t be blamed personally for some systemic problems he inherited, but it’s hard to sort out how much of the nation’s recent transportation woes are actually Buttigieg’s fault. At the very least, he hasn’t met the high expectations some had for him when he first joined the Biden administration.

So it wasn’t surprising that when Senator Debbie Stabenow of Michigan announced her 2024 retirement a few weeks ago, Buttigieg wasn’t among the rapidly forming field of potential Democratic successors. When asked this past week whether he’s considering a run for the Senate or the presidency in 2024, Buttigieg told Punchbowl he’s far too busy to think about any of that. “I don’t have any plans to do any job besides the one I’ve got,” he said, according to Politico.

The truth is, Buttigieg would have been a long shot for a Senate nomination in his recently adopted home state even if his first two years in Biden’s Cabinet had been exceptional. But it seems Transportation secretary won’t be just a quick and easy layover on the way to higher office for Mayor Pete. The best thing he can do for his political career right now is to return the Department of Transportation to the back pages of newspapers. Then, perhaps, he can run for office again or accept another appointment in which he doesn’t have to worry about complex supply-chain problems or airline crises foiling his big ambitions.

More on Politics

- Trump Is Threatening to Invade Panama, Take Back Canal

- Everyone Biden Has Granted Presidential Pardons and Commutations

- What Happened to Texas Congresswoman Kay Granger?