For a moment, the right’s longtime dream of an alternative social media seemed within reach. Various companies had been trying to build alt-Facebooks and alt-Twitters and alt-Reddits for years, of course, but they remained marginal. Then came 2020. New, sloppily enforced policies around COVID, election denialism, and QAnon actually placed a meaningful portion of the American public on the wrong side of mainstream platform rules. A Democratic fixation on disinformation docked snugly with the right’s warnings about patronizing, censorious libs. For once, there was a clear story, and a large audience was ready to hear it. Mark and Jack suppressed Hunter’s laptop! YouTube was demonetizing videos about vaccines and voting machines! Twitter and Facebook banned the actual president!

A series of platforms lined up to snatch defeat from the jaws of victory. Trump attached his name to Truth Social, a Twitter clone, which got hacked before it launched and which has come to resemble a comment section of the former president’s personal blog. Gettr, founded by former Trump adviser Jason Miller and funded by exiled Chinese billionaire and Steve Bannon associate Guo Wengui, never got the coveted Trump sign-up, effectively dooming it to obscurity. Parler developed an active base of users who then employed it to help plan and extensively document their assault on the United States Capitol, landing it a ban from both Apple’s and Google’s app stores as well as Amazon’s hosting platform; by the time it was allowed back, its users had moved on. (Last year, Kanye West claimed he would buy the site, then quietly backed out. Its parent company soon laid off most of the staff.) Whatever slim hopes these platforms held in 2022 were truly destroyed by Elon Musk, who bought Twitter and promptly restored its status as a safe space for the right. Who needs Truth Social when Twitter’s owner is tweeting, “My pronouns are Prosecute/Fauci”?

One alt-social platform, however, rode the post-Trump wave without wiping out: Rumble.

Founded in 2013 as an alternative video-hosting service, Rumble more recently rebranded as a “neutral video platform” designed to be “immune to cancel culture.” In 2021, The Wall Street Journal reported that the company had taken investment from “a group of prominent conservative venture capitalists,” including Peter Thiel, J.D. Vance (now the junior U.S. senator from Ohio), and former Trump adviser Darren Blanton. Rumble went public last year during the SPAC mania, and shares in the company (ticker symbol: RUM) now trade on the NASDAQ; it is worth just over $3 billion. In 2022, Bloomberg reported that Rumble was among the “best performers this year among firms that merged with a special-purpose acquisition company” and that it’s “sort of” a meme stock. Last year, Rumble announced it would take over hosting and advertising duties for Truth Social and plans to offer “cloud services” more widely. According to its latest quarterly public disclosures, Rumble claims 71 million monthly active users (up from 36 million the year prior) and lost $7.8 million on $11 million in revenue, while sitting on $356.7 million of “cash and cash equivalents.” Its IPO reportedly made the founder, Chris Pavlovski, a billionaire.

Rumble meaningfully exists, in other words. It gets real traffic, and it’s growing, which sets it apart from most of its peers and makes it the most significant player by default in the right’s larger attempt to create an internet infrastructure of its own. While the right may wish for its own Facebook or Reddit or Twitter, Rumble stands as proof that what it needs most of all, for a variety of old-fashioned reasons, is a place to monetize video. It needs a YouTube — and that, because or despite the company’s talk about free speech and political censorship, is what Rumble is trying to be.

In form and operation, Rumble looks familiar. It’s a video site with a follower model and all the expected social functions: voting, commenting, and a sidebar of other videos to watch. Its website is misleadingly old-fashioned; its app is more polished and shamelessly YouTube-like. Videos are organized into a broad range of categories — Viral, Finance, Sports — but its most popular content is often about politics. For a new user, signing up for Rumble feels a bit like logging in to a YouTube account that’s stuck in a right-wing recommendation loop.

Most “social network for X” concepts aren’t so much alternatives as jokeless parodies of services that are codependent with their users and therefore almost impossible to replicate — there’s a reason Musk had to buy Twitter instead of just creating a clone.

In contrast, the concept of an alt-YouTube is at least coherent. YouTube is less a social network than a streaming service with social features and an upload button — alternatives can succeed by offering content that YouTube doesn’t, either by subsidizing it or merely allowing it. In fact, there are already dozens of YouTube clones that look and feel like the platform, with billions of users, vibrant economies, and world-famous creators, all committed to providing a place for content that YouTube openly suppresses or would never monetize. For the most part, though, they host porn.

This is an obvious path forward for a true YouTube alternative: not literally porn but content and creators forbidden or unable to monetize elsewhere. Keep in mind that YouTube has been unique among social internet platforms in its ability to generate real money for its talent, helping a not insignificant number of political commentators and pundits — many of them right leaning — to become millionaires. It has for years been a vital place for conservatives to build audiences and an environment where certain sorts of right-wing content did remarkably well. Plus, on YouTube, you could actually get paid.

If you listen to how Rumble talks about itself, you’ll hear about a place where you can find content that the censorious corporate busybodies at woke YouTube don’t want you to see. That is, at best, half true. The reality on the platform is that many of the top creators are movement celebrities who produce little if any original content for the site, mostly reposting TV clips and podcast episodes from traditional conservative media outlets and even from YouTube itself, where many still post freely: Dinesh D’Souza, Charlie Kirk, Steven Crowder, Ben Shapiro. These voices are not otherwise silenced or even hard to find. (And Rumble has plenty of rules, which, like YouTube, it can enforce as it pleases.) While many right-wing stars have found a large audience on Rumble, success there among this set is not distributed evenly — as Miles Klee noted in Rolling Stone, some have substantial followings on the platform but generate very few views.

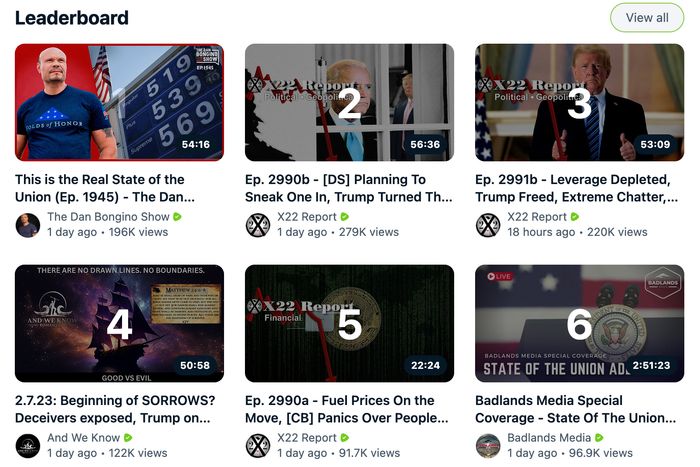

For those looking for material that has or actually would be banned at Youtube, Rumble does have plenty to stream: the platform’s leaderboard regularly features quasi-religious Qanon shows and unabashed racists. Many of those creators, however, are using Rumble as a backup distribution system or hosting platform for linking or embedding elsewhere, on sites like Parler or Reddit clone Patriots.win, formerly thedonald.win, formerly /r/the_donald. They’re not yet ready to go all in.

But Rumble clearly aspires to do more than serve as a secondary host for conservative podcasts, Fox News segments, and QAnon shows. It has started building its own more varied roster of talent — in some cases snatching up creators who are banned elsewhere and in others convincing them with juicy deals to go into self-imposed Rumble exile. Dan Bongino (soft g), one of Rumble’s most popular creators, announced his investment in Rumble after YouTube demonetized his videos. In late 2022, Rumble welcomed former kickboxer and mega-popular “manosphere” influencer Andrew Tate, who was banned from YouTube and TikTok, in a deal CNN reported was worth $9 million. (Tate was more recently arrested by Romanian authorities on charges of rape and human trafficking.) Prank YouTuber and Nelk Boy (don’t worry about it) SteveWillDoIt, who claims to have been banned for violating YouTube’s policy on gambling content, gets prime placement, as does Russell Brand, who, after repeated warnings from YouTube concerning mostly COVID-related videos, announced in September that he was “quitting” YouTube for a deal with Rumble (he still posts videos on both platforms). In January, the company announced a partnership with Power Slap, “the world’s premier slap fighting organization” (it is what it sounds like), with an “all-new exclusive show on Rumble focused on the sport.”

Journalist and pundit Glenn Greenwald, a frequent critic of mainstream tech platforms, has partnered with Rumble for a daily cable-style news show called System Update and migrated his popular Substack to Locals, Rumble’s Patreon/Substack–style subscription platform. Greenwald has also become perhaps the platform’s most visible advocate on Twitter.

Greenwald is correct here to say that Rumble is not exclusive to or exclusively for conservatives: It’s an open platform, anyone can sign up, and some of its early paid creators, including Brand, aren’t right-wingers. But to a new user with no background knowledge of the site — or one with limited patience for Greenwaldian debates about political self-identification — Rumble remains, functionally, a conservative video aggregator. Its “Battle Leaderboard” as of February 7, from the top: an episode of The Dan Bongino Show; a QAnon broadcaster; a show from a former Fox News anchor; an episode of Triggered, a twice-weekly Rumble exclusive hosted by Donald J. Trump Jr; and another QAnon guy. Ron DeSantis has an active account there, and Rumble is, according to the company, officially Kevin McCarthy’s “preferred platform.”

Another way to look at Rumble — another reason it has succeeded as a business where other alt-social projects have failed — is as an insurance policy for a segment of the media that, like virtually all news-and-politics-adjacent online media in 2023, is staring down a fairly grim and uncertain financial future. While Rumble’s pitch to users is still muddled, its theoretical promise to certain media personalities is fairly clear: Come here, bring your audiences, we’ll try to figure out how to get you paid, and in the meantime we may just hand you some cash. When addressing creators, Rumble talks about money. It appears to have made Bongino, a conventional conservative talk-radio and television host who took over Rush Limbaugh’s AM slot in some markets, fantastically wealthy through its public offering. It’s an attempt to build an infrastructure around the various sorts of shows — cable-style shows, podcast-with-a-camera shows, whiskey-and-leather-chair talk shows, hyperexpressive YouTube-style monologue shows — that have become the true currency of conservative influence in the 2020s.

Rumble’s recently launched ad network is one part of the effort to put money into the pockets of conservative content creators, but I suspect that building a stable of free-speech-curious advertisers that can support YouTube-level advertising rates, even with a more generous cut for creators, will be quite difficult. If I had to guess, its subscription feature, Locals, will probably be what makes or breaks the platform for contributors who don’t have one-off contracts.

While at its core, Rumble is an attempt to build a parallel YouTube-style monetization platform, it is also the latest company to be born from a familiar right-wing media critique — in this case, rewritten in social-media terms and backed by venture capital. “YouTube, Twitter, and Facebook are not places that have been purged of conservatives,” says political historian Nicole Hemmer, author of Messengers of the Right: Conservative Media and the Transformation of American Politics. “It is not true that they’ve been shunted into the parallel economy. But it’s important that it feels like they have been. This idea of building alternatives is a political argument, and it reinforces the idea that any place that isn’t rigorously conservative must be a left-wing institution. We get sidetracked by new technologies that are doing the same old thing.”

In September, Pavlovski rang the NASDAQ opening bell and gave a brief speech about his now-public company. Rumble, he said, was going to “push back against all these other companies that are tilting the internet one way.” (Rumble did not respond to emailed requests for comment.)

“I look forward to tilting it back,” he said, “and bringing it back to the middle and as neutral as possible.” Compare this language to the coverage of the launch of a certain cable news channel in 1996:

Rupert Murdoch said recently that he felt a more conservative cable news network was needed to counter the “liberal” CNN. [Roger] Ailes, a veteran TV producer who joined NBC in 1993, has also worked as a strategist and media consultant for Republican presidential candidates.

Ailes said the new network will not have a political bias. “We’re not starting up a reactive news service in any way,” he said. “Our job is to be objective, to do fine journalism.”

The partisan funding! The neutral pose! The desire to restore “balance”! You might recall Fox’s devotion to early mottos — “Fair and balanced” — as well as the exhausting years-long debate with the rest of the media about whether the plainly conservative network had a bias or a point of view. Rumble’s equivalent to Fox’s “news division,” which the network could gesture at when critics noted the popularity of its conservative opinion shows, is its open platform, on which liberals and progressives are as free as anyone else to upload videos for nobody to watch. Fox didn’t “restore objectivity” to the broader media in any meaningful sense, but it did become the center of gravity for a generation of conservative media. It also made a lot of money.

Early Fox News was plainly influenced by talk radio and drew from its ranks for talent; Rumble’s early bids for talent can be viewed in a similar way. (Not for nothing, Rumble investor Thiel has expressed past interest in creating a new cable news network.) Last year, the company announced the launch of “Content+,” also a way for Locals users to “monetize movies, specials, and other on-demand content.” Among the first notable films distributed through the platform was D’Souza’s 2000 Mules.

Rumble is, in other words, a project with lots of precedents: a well-funded attempt to build a parallel but not entirely separate media ecosystem that just so happens to meet the needs of America’s conservative movement, which, at the moment, means providing a set of tools to make sure lucrative ideological media remains monetized to the fullest extent possible. Rumble doesn’t have to take on YouTube to succeed, nor does it have to replace Fox News. It simply has to get its people paid.