This article was featured in One Great Story, New York’s reading recommendation newsletter. Sign up here to get it nightly.

On a brisk Tuesday morning while most are still asleep, Eugene Toussaint is in the gym by 6 a.m. before a marathon day as a criminal-defense attorney with the Legal Aid Society, the city’s largest provider of public defense.

It’s a 40-minute drive from his home in Sunnyside, Queens to the office in Kew Gardens where, between sips from a large Dunkin coffee on his desk, he waits for a pair of clients he’s scheduled to meet. The first meeting at 9:30 a.m. is brief, with Toussaint pointing to his calendar on his computer as he patiently explains to the client the next steps of the case. As the clock creeps closer to 10 a.m., it’s clear that the second client is a no-show. Toussaint takes it in stride — it spares him precious time he can’t afford to lose. With a full day in court ahead of him, arriving just a few minutes late can set his day back by hours.

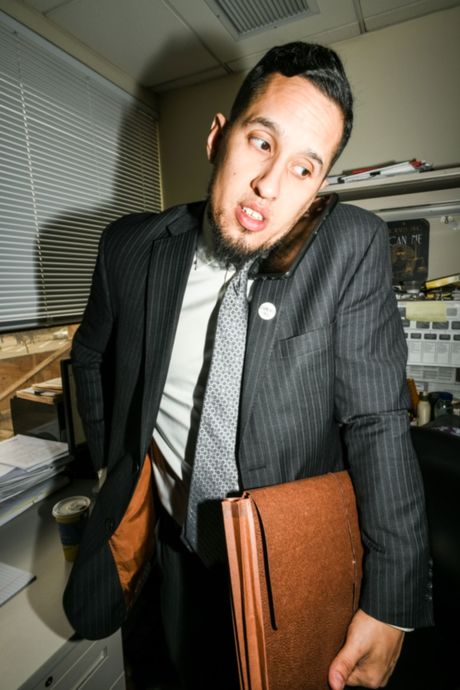

As Toussaint walks the few blocks over to the Queens Criminal Court with a black leather jacket draped over a gray suit, he describes his approach to his clients simply: “Nobody is as bad as their baddest day.” The courthouse is bustling as he walks past a winding line of people waiting to make their way through security. On the wall above them is a variation of a quote from Cicero inscribed in gold: “Justice is the crowning glory of virtue.”

From that moment on, the day is a blur of staircases and elevator rides, hustling from one freezing courtroom to the next. Clients wait for their lawyers in the courtrooms, sitting on old wooden benches marred by scratched out messages and the occasional piece of gum. When Toussaint calls their name, they go out to meet in the hallway to discuss their cases. He stands alongside other attorneys doing the same, at one point balancing his full accordion file folder on a nearby railing as others weave their way through the crowded, humid hall. They go back in the courtroom to stand before the judge for the next stage of their case under the buzzing fluorescent lights.

With time in between meetings, he takes a lunch break around 1PM, grabbing wings and fries at a nearby bar. Toussaint finally can take a breath. “I feel like the only time I get to myself is going to the gym in the morning,” he says.

That’s because this is only his first job of the day.

After court, he will drive nearly an hour to the Bronx River Houses where he works as a home health aide for his aunt who was diagnosed with cancer. There, he spends the next three hours doing her laundry, shopping, cooking, and cleaning. While caring for her, he’ll sometimes bring some of his files along to work on as well. When he finishes around 9 p.m. he will occasionally pick up a third job as an UberEats driver before heading home.

Toussaint’s intense schedule is not uncommon. The attorneys working for the Legal Aid Society are under immense strain thanks to a funding crisis that’s led to high turnover of crucial staff due to immense workloads and chronically low salaries. The public defenders who haven’t left for better-paying jobs are forced to take on additional cases from their departing colleagues. And like Toussaint, sometimes they pick up outside work to afford living in one of the nation’s most expensive cities while shouldering heavy student-loan debt .

The nonprofit, which provides its services for free to low-income New Yorkers who qualify, receives the majority of its funding from both the city and the state. That funding has not kept up with skyrocketing costs for rent, utilities, health insurance and their labor contracts which increase three percent every year. “We are in a fiscal crisis and it’s unsustainable,” said Twyla Carter, the organization’s chief executive officer.

In November, Carter sent a letter to Mayor Eric Adams, requesting $82 million in additional funding from the city to address these costs, improve Legal Aid’s ability to retain and recruit staff, and update antiquated technology. She also called on the city to change its slow-moving contract process, which causes Legal Aid to have to wait so long for reimbursements that it sometimes struggles to pay vendors and make payroll. “The real devastation outside of dollars and cents, it’s our staff and attorneys,” she said. “They can’t keep doing this. We have folks that have second jobs. We have folks that are leaving for other jobs to move out of the state and we can’t replace them.”

The attrition rate for Legal Aid’s staff last year was 80 percent higher than the previous year and 2023 appears to be trending even higher than that. Currently, there are 328 vacancies, 180 of which are attorneys while the remaining 148 are paralegals, investigators, social workers, and other administrative staff. With a starting salary for a new attorney of $74,909, it’s often hard for Legal Aid to compete with other employers, such as government agencies or high-paying law firms where attorneys often handle a smaller number of cases.

“We’re often the adversary to a government player, right?” said Dawne Mitchell, the chief attorney of Legal Aid’s juvenile rights practice. “And so our government players, they have lower caseload standards and higher pay. We have higher caseload standards and lower pay. It makes no sense,” she said. “It sort of creates this inequitable system or continuation of an inequitable system. And the folks who are harmed by that are our clients as well.”

When one attorney leaves, their clients get handed off to another attorney who is usually unfamiliar with the case and overburdened with dozens of their own, contributing heavily to a backlog of cases in the courts. “An overworked attorney? That equals an injustice to a human being that’s being accused and that’s the part of the problem that should resonate with everybody regardless of your political affiliation, regardless of your viewpoints on public safety,” said Tina Luongo, the chief attorney of Legal Aid’s criminal defense practice. “The fact is that we are a system that promises justice when you’re accused and we’re failing at that because we don’t have the structure and the funding and the support for both sides of the equation, DAs and defenders, to be able to actually do it in the way in which justice would be served.”

Toussaint, who has worked for Legal Aid as a public defender since 2014, has seen the effect, having to pick up more arraignment shifts at the courthouse where attorneys are assigned to cases. With less attorneys, those shifts are divided up among less people which results in picking up more cases. His current caseload consists of 106 active cases, all in different stages of completion. High attrition can also affect the attorney-client relationship, something that’s crucial to the job. “I know, personally, it’s very hard to establish the same connection you have with a client you’ve gotten from the very beginning with a transfer client,” he says. “The connection I establish with my client, it’s very critical.”

Toussaint predicts a larger crisis on the horizon for the Legal Aid Society. As employees of a nonprofit, attorneys are eligible to have their loans forgiven by the federal government due to their work in a public service role, and he believes many of his colleagues will consider leaving once the burden of massive loan debt is off their shoulders — even if they’re passionate about the work. “It’s a cost-reward thing, right? So, even if you’re really good at it, it’s a job that burns you out. It’s an emotionally stressful job,” he says. “And to have that experience without being properly compensated for it, it just adds to it.”

He knows this feeling better than most. Despite making around $85,000 a year, Toussaint is carrying $400,000 in student loans after graduating from St. John’s University School of Law. He has about two years left of payments before he can start applying for forgiveness, but even when that day comes, Toussaint says he would likely stay at Legal Aid because he likes his job. Though, he would consider going part time to focus more on a legal-affairs podcast he’s started and invested significantly in, Attorneys with Swag, which would benefit from him staying in the legal world.

Sarah, who worked as a Legal Aid attorney for nearly five years, couldn’t afford to stay. She was raising two children by herself on her salary while carrying $100,000 in student loans. (Sarah is a pseudonym.) “I finally felt like I just couldn’t find a way to keep making it work. I was like, I’m just gonna keep digging myself into a deeper hole and not really get out of it,” she said, adding that the breaking point came when her offer on a home was rejected due to her financial condition. “It was coming down to a choice between, do I stay at a job that I personally love or do I think about the future I want for my kids?” A few weeks ago, she left for a job in private practice that pays $40,000 more. “I’m hoping in a few months, I can really buckle down and be out of debt and that’s something that if I had stayed at Legal Aid, I don’t know would have happened at all,” she said.

Public defenders have found themselves an unlikely ally when it comes to funding: Prosecutors, whose offices are also contending with a budget crunch and loss of staff. In the fall, the city’s five district attorneys joined with Legal Aid and other prominent public defense organizations to send a joint letter to Adams to press him for more funding. When Adams recently testified before the State Senate in Albany about money for the city, he spoke directly about the need to fund both public defenders and district attorneys in the city, saying they’re “overwhelmed.”

But according to Luongo, they have yet to make significant progress with Governor Kathy Hochul. As part of her budget proposal for the coming year, Hochul is requesting millions of dollars in additional funds to the state’s program supporting prosecution, but hasn’t allocated comparable amounts of money specifically for defenders. A spokesperson for the governor said in a statement, “Governor Hochul’s Executive Budget makes transformative investments to make New York more affordable, more livable and safer, and she looks forward to working with the legislature on a final budget that meets the needs of all New Yorkers.”

By the time Toussaint’s day in court is through, he has consulted with more than a dozen clients. And when he returns to his office in the late afternoon, he begins preparing for the 21 cases he’s slated to handle on Thursday. Despite it all, he’s light-hearted, cracking jokes throughout the day. It’s a well-worn ease that took time to build. “I won’t lie. It used to stress me out a lot, but I’ve finally adjusted,” he says.

Even so, Toussaint is honest about the struggle. He hopes that he and his wife can one day afford to buy a house, but between the debt and the uncertainty with Legal Aid, it’ll be a long time before that’s possible. “It’s not a very fun life,” he said with a small smile. “Dreams come at a high price, man.”