When Joe Biden’s closest political allies started receiving invitations late last year to occasional private calls with his top advisers, they universally interpreted the sessions — updates on messaging strategies and governing priorities — as a sign Biden was gearing up for reelection. When early-state power brokers got called in for meetings of their own, they were almost sure of it. There was little question by the time top Democratic donors who’d spent two years griping about being ignored were invited to White House Christmas parties for the first time. And when, late in March of this year, some of Biden’s most influential supporters found themselves scheduled for a surprise series of small check-ins with senior staffers over the next month, it seemed that a formal announcement might by now basically be just a formality.

One of the most tiresome conventions of today’s politics is the notion that someone isn’t running for an office, especially the presidency, until they officially declare that they’re doing so, no matter how obviously they’re taking the necessary steps. (Ron DeSantis is raising money, building a staff, and visiting influencers in important states all over the country? Totally not running!) Biden, for one, has been making almost all the moves needed for any reasonable person to conclude he’s actively pursuing a second term — even as pollsters continue rolling out results showing misgivings or wishes for alternatives from his supporters. (Most recently: A Marquette Law School survey showed that only half of registered Democrats want Biden to run.)

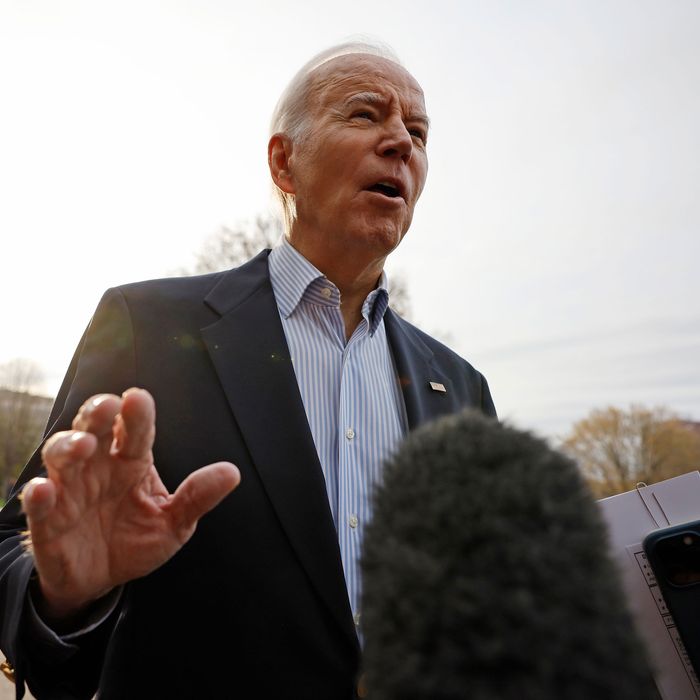

In Biden’s case, semi-informed chatter about a late-April launch that might get pushed into the summer has often been overtaken in the public conversation by worries about his age — he’s 80, and would be 86 at the end of a second term — and rote whispers that he could still decide not to re-up. Yet at the same time, longtime Washington types have interpreted his recent apparent embrace of a centrist path, such as approving an Alaskan oil-drilling project and the blocking of a D.C. criminal-system overhaul, as a pre-reelect pivot. (Biden has simultaneously tried to keep Bernie Sanders, avatar of the left, in the fold by having him over for private dinners and making sure he maintains a relationship with the new White House chief of staff, Jeff Zients.)

The truth is simple, according to Biden’s longtime friends, top Democrats, and people close to the White House: Biden always takes his time announcing his bids, and we should treat him as if he’s running until he isn’t. He’s in no hurry; plenty is still uncertain about how his rollout will look — some close to the administration are trying to work out who will show up to headline the big annual fundraising dinner for the first-to-vote South Carolina Democrats later this month, for one thing — and he could, of course, still change his mind. But doing so now would mean shutting down a process that’s been in motion for months, as well as setting off an unprecedented scramble to succeed him within the party.

Once it’s all tallied up, it’s hard to ignore the evidence that Biden 2024 is already here.

Northeast Corridor Maneuvering

You don’t decide to unionize a campaign that isn’t happening. That was the basic takeaway from those in Biden world’s outer orbits when, late in March, the Associated Press reported that a theoretical campaign would be the first presidential reelect with an organized staff. The decision, it seemed, had already been made. The team’s logistics are being sorted out.

That was part of the story. For months, Biden has been meeting quietly with a tiny group of advisers — led by senior White House staffers Anita Dunn and Jen O’Malley Dillon, who ran his last campaign — to map out this campaign’s contours and enlisting a slightly larger group of aides, including longtime inner-circle members like Steve Ricchetti, Mike Donilon, and Bruce Reed and younger senior staffers like adviser Julie Chavez Rodriguez and digital chief Rob Flaherty, to work through some more logistical and strategy specifics.

Those meetings, and their offshoots, have advanced beyond long-running debates over where to place the campaign HQ. (Some staffers hesitated at relocating to Wilmington, or even back to Philadelphia, where Biden’s 2020 bid was based, preferring to stay in D.C.) And they have gone deeper than just trying to identify a specific campaign manager. The core team members are looking to build a broad roster of strategists who can work closely with the handful of close Biden aides who won’t leave the White House but will instead effectively run the show from inside the government. They have met with alums of Barack Obama’s campaigns as well as of Biden’s own past races and even onetime opponents’, like those of Cory Booker, Steve Bullock, and Beto O’Rourke, as well as Kamala Harris’s presidential teams.

Meanwhile, Building Back Together, the main outside group pushing Biden’s agenda on the airwaves, reshuffled its leadership in recent weeks to empower a strategist with special experience working with Latino voters and another who is close with Obama. And even the White House’s own underappreciated personnel moves are revealing: Replacing Kate Bedingfield, Biden’s longtime communications director, earlier this year was Ben LaBolt, a former Obama aide who served as the 2012 reelection campaign’s chief spokesman.

Marianne Stands Alone

You might think that, given the flood of polling showing Democrats still unsure about Biden running again, he’d be facing real opposition. That his only declared challenger is lifestyle guru Marianne Williamson says plenty. That none of the other onetime contenders wants to even get near this conversation says far more.

It wasn’t long ago that a long line of governors, senators, and House members were hearing pleas from donors and strategists to think seriously about 2024, either as Biden challengers or (more likely) as fallback plans in case he decided not to run in the end. Yet that talk is an ancient memory; those pols have gotten the message — sometimes directly from people close to Biden — that there’s no ambiguity left in which they can maneuver.

So Ro Khanna, the California congressman and onetime Sanders ally who got closest to considering a challenge, hasn’t visited an early-voting primary state in months and has publicly backed Biden. Gavin Newsom, the California governor who insisted on more boldness from his party last summer, stepped back from plans to make a big speech about democracy after the midterms, opting instead to start a PAC attacking red-state leaders. Governors J.B. Pritzker and Phil Murphy have doubled down on their fundraising efforts for the party after rumors that they’d consider running if Biden didn’t, and both have visited the White House this year. One of Pritzker’s former senior aides — Quentin Fulks, who more recently ran Senator Raphael Warnock’s successful reelection campaign in Georgia — has even talked to the Biden side about lessons from his last race with questions of national strategy looming. And Gretchen Whitmer, the oft-mentioned Michigan governor, has recently skipped right past 2024 in a series of interviews but seemed perfectly happy to recenter conversation about her future in 2028. (“I think that this country is long overdue for a strong female chief executive,” she just told the New York Times.)

Publicly backing off is one thing: Biden is likely to have widespread support from his party’s leaders, and no one sees any upside in playing a spoiler role at this point. But dissuading donors and supporters from even talking about 2024 indicates a deeper level of certainty at high reaches of the party that the decision has already been made. The calls to early-state influencers have dried up entirely, and none of the just-in-case crowd will admit to being even theoretically interested when pressed by senior party figures in private, according to Democrats who’ve been part of such conversations.

The result? As one such Biden-allied honcho predicted, “If Marianne Williamson is all he’s got to worry about, he might as well take a nap during the primaries.”

Follow Air Force One

It’s often said in D.C. that a politician’s most important resource is his or her time, and even a quick glance at Biden’s recent schedule tells a pretty vivid tale about his priorities.

Between popping overseas for a series of recent trips and to tragedy and disaster sites Stateside, Biden has been ramping up his domestic-travel schedule. And for the most part, the trips are about big-picture messaging on his administration’s accomplishments and the opposition’s extremism — not to sell any specific legislation. That itself is reason enough to believe that Biden’s easing into campaign mode. The specifics make it even more plain. Just look at most of his stops in the last seven weeks or so.

Where did he choose to unveil his budget plan in early March? Philadelphia. That’s not just the city he associates most closely with his 2020 victory after his old home state handed him the election, but also the site of his last campaign HQ and the biggest voter trove in the swing state that takes up the biggest share of brain space for both Biden and Donald Trump. That trip wasn’t long after he promoted his party’s work on health care and warned of Republicans’ threats to coverage in a swing through Virginia, a traditional battleground state that had been trending blue but is back on the national radar since electing a GOP governor in 2021. Shortly after his Philly trip, Biden was in yet another top-tier swing-state city — Las Vegas — to talk up his work on drug prices and to raise money. Not long after that, he chose North Carolina — a red-leaning swing state featuring a Democratic governor and an aggressive Republican legislature — to kick off a tour touting his economic plans.

The pattern isn’t terribly subtle — Jill Biden has also been to Ohio and Colorado recently — and it fits in with his DNC’s monthslong efforts to get party infrastructure ready in eight politically vital and swingy states. During the midterms, the committee — at Biden’s behest — spent the bulk of its money on laying groundwork in Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin. He’s keeping up the focus on purple areas: In early April, he hit Minnesota, a blue-tinted state that Trump allies nonetheless continuously crave, for his economic tour’s second stop.

As Trump Goes, So Goes …

Biden’s always been pretty clear with his confidants that a 2024 run would largely be premised on the idea that he has to save the country from the return of Trumpism — and Trump specifically. Even in Biden’s lowest political moments in the first half of his term, his advisers tried to keep his (and the press’s) focus on that possible matchup, circulating head-to-head polling between the two of them as a counterargument to Biden’s sagging approval ratings and repeated findings that Democrats were unsure about the wisdom of round two.

Though few admitted it out loud, many liberals were eager for Trump to play a prominent role in the midterms to help clarify the stakes and terms of debate. And once the dust settled, that view became even more prominent. “Democrats overperformed because voters disliked Republican candidates more,” wrote a pair of Biden-aligned pollsters in the aftermath.

So now, with Trump a fully fledged candidate again and dominating news cycles even before he was indicted at the end of March, Biden allies are watching the opposition party’s convulsions as closely as ever. And as Biden hasn’t budged from his contention that he is best positioned to vanquish Trump, recent polling only supports his insistence that he must act as a steady-handed foil who can highlight right-wing madness. While the country was on Trump-indictment watch, Fox News found the ex-president doubling his primary lead over would-be challengers like DeSantis, breaking 50 percent support.

He’s Just … Saying It Out Loud

One unfortunate side effect of the Trump years was the political world’s inability to believe much unless it was uttered “behind closed doors” and surfaced via leak. Among other things, that means less attention is being paid to what’s actually coming out of the president’s mouth in front of mics and cameras. But in this case, we should really just take Biden at his (oft-repeated) word.

Take, for example, his “joke” while awarding author Colson Whitehead a National Humanities Medal at the White House in March. Noting that Whitehead won Pulitzer Prizes for consecutive novels, Biden grinned, “Pretty good, man. I’m kind of looking for back-to-back myself.” That actually indicated some progress from late last year, when he looked exasperated to be presented with yet another poll showing voter skepticism in a second term even after his Democrats overperformed in the midterms. His message to those skeptics? “Watch me.”

Of course, it’s true that Biden hasn’t outright said he’s running. It’s also true that in the past, aides have had to remind him repeatedly not to say it until he formally launches his campaigns, for fear of triggering federal election regulations before they’re ready. But he’s been consistent since taking office, telling anyone who asks — and it comes up in basically every interview he’s done — that running again is his “expectation.”

If you’re still unconvinced and need to hear it from someone a little less prone to slips of the tongue, though, fine. How’s Ron Klain, Biden’s former chief of staff, at his departure ceremony earlier this year? “As I did in 1988, 2008, and 2020, I look forward to being on your side when you run for president in 2024,” he said to the president. A few days later, he hinted to me that the broader band would soon get back together, saying that Bedingfield, Biden’s outgoing communications director, would also “continue to remain a critical player in moving the Biden agenda forward from the outside.”

If that’s not enough, perhaps Jill Biden’s recent comments will do the trick. Speaking to the Associated Press in Nairobi, she conceded that the only thing left — “pretty much” — was to decide the logistics of the announcement. “How many times does he have to say it for you to believe it?” she asked.