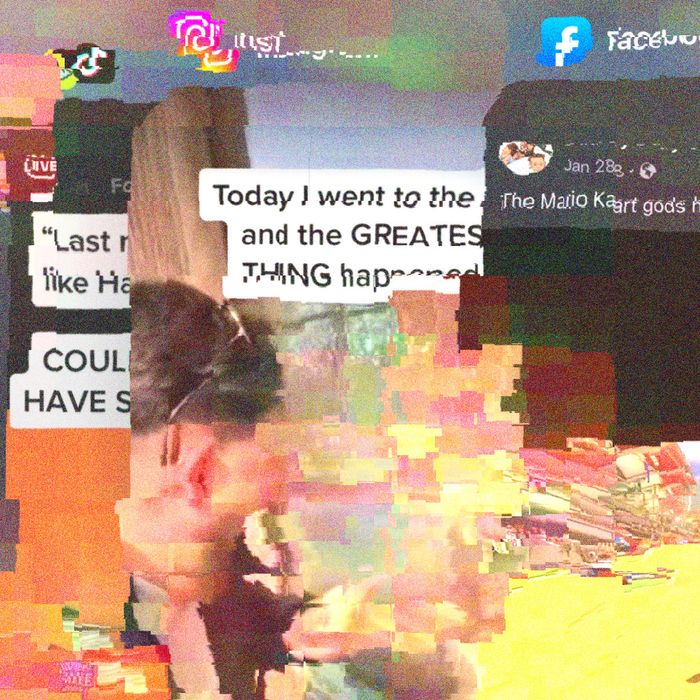

You’re stuck in line at the grocery store, so you check your phone. Your brain shuts off, and your thumb takes over. Soon, a tall video plays. A man is tricking a baboon with some sleight of hand. He makes a lighter disappear and the baboon makes a weird expression. Laughter. The video starts again. The baboon is confused, and so are you. Who made this video? Nobody you’ve ever seen before. Why are you watching it? Because the app showed it to you. Wait, which app did you open, again? The video is captioned like a Snapchat post, with a bar of fine white text over a smoky banner: “This monkey loved my magic trick 💀💀.” There’s another caption, too, apparently written by someone else, this one in a TikTok font: “Today I went to the zoo and the GREATEST THING happened …” To the right, you see a vertical row of icons: hearts, a voice bubble, and a paper airplane that suggests you send the video to someone else (who? where?). Lots of big numbers. You swipe down. A thunking scroll produces another video, then another, then another.

You’re on Instagram, it turns out, but you could be anywhere. This is what all the apps are like now after TikTok.

The government can try to ban TikTok — and may actually follow through — but in this way, TikTok has already won: It drove its competition to madness. The big social apps now feel increasingly the same because they’re filled with the same stuff: content their users didn’t ask for made by people they don’t know on platforms they may not even use. Where they used to see posts from people they know, now there are algorithmically suggested videos from somebody made for nobody.

The first part of this story is simple enough. By the time TikTok showed up, its biggest competitors were already getting old. When it started stealing users and their attention, the apps simply copied it, as is industry custom, without hesitation or shame. Instagram, Snapchat, and Facebook were redesigned to look, feel, and in some cases recommend content more like TikTok’s. YouTube nagged creators to post “Shorts” and tried to get users to watch them. Now, the first thing Twitter users see is algorithmically scavenged content in a feed called “For You.”

The tech industry’s TikTok psychodrama was evident to anyone with a social-media account, but at first it seemed like the sort of thing you might be able to ignore. It was just a bunch of new TikTok-style features implanted into old interfaces, right? Social-media professionals — influencers, “creators,” or anyone with a desire or need to keep their numbers up — knew better. Instagram made it very clear that the only way to stay relevant on the platform was to post lots of Reels, and it started paying creators to use them. Snapchat lured creators into Spotlight, its TikTok clone, with the prospect of big payouts. Prominent YouTubers started cranking out Shorts not because they wanted to, or because their audiences asked them to, but because YouTube told them to and YouTube is their boss.

These companies weren’t just going through a TikTok phase, in other words. They were up to something else. While TikTok was adding users who were each spending astounding amounts of time on the app, Meta, Google, Twitter, and Snap were struggling toward more modest goals: goosing slow growth, keeping people from leaving, extracting more revenue from each remaining user, and keeping those users engaged, at all, by any means possible. Whatever first motivated the rush to copy TikTok’s design and methods for surfacing content, two things quickly became clear. None of these companies could really compete with TikTok on its own terms or win back users from the platform.

What they could do, though, was increase engagement by showing their users a whole bunch of short videos, often from people the users don’t know, recommended by an algorithm. “Being able to accurately recommend content from the whole universe that you don’t follow directly unlocks a large amount of interesting and useful videos and posts that you might have otherwise missed,” Mark Zuckerberg told investors last year in reference to Meta’s content-recommendation plans.

Zuckerberg already knew this, of course. Everyone did. In recent years, Facebook, YouTube, Instagram, and Twitter have become increasingly assertive in recommending content from users other than those you follow, according to some combination of your presumptive “interests” and the likelihood that you, or a general user, will end up watching it. The appearance of such content was a source of complaints directed at every major platform before TikTok arrived on the scene — most memorably on Facebook, where the News Feed gradually transformed from a place for users to keep up with people they had connected with on purpose into a stream of content recommendations from strangers. The trade-off was clear: In exchange for more of a certain kind of engagement from your users, you make their experiences subtly worse, or at least less personal, under the guise of “personalization” (there is perhaps no more impersonal form of content than the second-tier “For You” recommendation). You show them another video of a dog getting rescued or a car crash from a dashcam or a horse getting its hooves trimmed. Your users may watch it, but they probably won’t share it because they have no connection to it or because of the weird (if not entirely incorrect) assumptions it seemed to make about them. They forget it and move on, ever so slightly more convinced that your platform is getting worse. But from the platform’s perspective, the user did watch the video.

Pressure from TikTok accelerated this change, forcing competitors — or giving them an excuse — to attempt previously unimaginable levels of engagement baiting. This was, again, doomed as a long-term strategy. TikTok is a place people go with the intention of seeing videos from people they don’t know; it’s also a place where the people making the videos do so with such an environment in mind.

TikTok is an opaque system in that you don’t know why it recommends the videos it does. It’s counterintuitive, but this opacity helps its recommendations feel right, or at least not out of place. You’re there to see something unexpected, and that’s what it gives you. In contrast, on social networks centered around people and feeds, content recommendations made by machine-learning algorithms sourced from users you don’t know feel out of place, incongruous, interruptive, and sleazy. They feel like what they are: desperate attempts to juice engagement based on a machine’s idea of what you want or need. They feel like ads.

The social platforms are marketplaces first and foremost, and their efforts to replicate TikTok’s FYP recommendation engine radically altered their incentives for creators. Meta, Google, and Snap have collectively spent hundreds of millions of dollars to fill their TikTok-style content ecosystems with suitable videos and, in some cases, pressured creators to get onboard either with implied threats of irrelevance or promises of artificially boosted engagement. These too are poor substitutes for TikTok’s appeal to creators, which is that it’s unusually likely for them go extremely viral in an actually culturally relevant way. Thus they have led to poor substitutes for TikTok content that is either produced under duress, in exchange for direct payments that creators know will dry up soon, or by content hustlers looking to harvest a bit more audience for themselves.

The early result was a collection of TikTok clones populated by knockoff TikToks. These videos had some superficial similarities to popular TikToks. They were tall, not wide. They were filmed in styles favored by TikTokers. They took stabs at broad virality through popular categories: food hacks; pranks; hyperconfident, tightly edited monologues; a thousand different joke formats. Whether or not they were any good, they were doomed to feel like counterfeit TikToks because they were distributed through counterfeit TikToks. People have created at least hundreds of millions of Reels for Instagram and Facebook, but there’s still no working definition of “a Reel” that doesn’t mention TikTok. These were not self-sustaining systems, nor did they make the platforms they were inserted into any healthier or more vibrant. (If anything, they further drained energy from the features that drew users to the apps in the first place.)

Another consequence was the proliferation through these platforms of actual TikTok videos ripped from their original context and shared elsewhere. (TikTok makes it extremely easy to download another user’s video to your phone, so the company is at least a little complicit in this dynamic.) This was officially discouraged but inevitable. Meta and others have internal tools to minimize the appearance of such content or to recommend fewer videos with visible TikTok logos; this has led to the creation of dozens of tools that can strip platform branding from videos. Ripped content is everywhere.

As a result, we now live in an era of omnipresent cross-platform video chum, churning away in each platform’s little designated TikTok zones and seeping in from their edges and floating up from the bottoms of their feeds. The social giants have become uncanny platforms full of uncanny content; in the process of becoming TikTok but worse, they’ve also become worse versions of whatever they were to begin with. If you scroll deeply enough on Instagram that you run out of posts from friends — which is getting easier as fewer of them bother to post — the platform starts showing you repackaged Reels, which are themselves often reposted TikToks, Twitter videos, or Snapchat clips. Twitter’s “For You” feed, while not yet dominated by video, has given birth to a whole new class of viral accounts dedicated to reposting sourceless viral content from elsewhere, while content from this new feed is osmosing into users’ primary feeds by sheer force of impression and changing the character of the service as a whole. (Elon Musk seems to want to make “For You” the center of the Twitter experience, which seems as if it will either render the service unrecognizable or, as Twitter’s utility as a place to find out what’s going on approaches zero, send it into a death spiral.) YouTube’s relatively tranquil video feed is now interrupted by rows of Shorts that are a little bit stupider or hornier or meaner than the videos above and below them and that wouldn’t feel out of place in an “Around the Web” module under an article you tapped on by accident.

For most social networks (most obviously Meta), the pursuit of TikTok has paid off in narrow ways, providing a much-needed, well-timed engagement stimulus — one they can’t afford to give up, even if they know it could be alienating their users. There’s no turning back unless, of course, they come up with something entirely new, and on this, past performance isn’t encouraging.

With this in mind, the suddenly relevant prospect of a TikTok ban suggests two futures. In one, TikTok remains available and continues to command dramatically more attention from its users than its older competitors get, while beginning to confront its own approaching plateau. Not ideal, if you’re Meta. In the other, TikTok is banned or seriously diminished. This would no doubt be a gift to American social-media platforms in terms of both user habits and raw advertising dollars. It would also reveal just how thoroughly they’ve been hollowed out over the years and how completely they’ve abandoned their core appeal in pursuit of a competitor they could never catch and won’t be able to replace in the event of its disappearance.

That America’s biggest social apps have been made to look shabby and desperate in comparison to TikTok is twice damning. When TikTok showed up, its competitors regarded it as crass and ruthless — less of a coherent social environment than a best-of compilation of existing app features (including a lot from Vine) combined with grimy growth hacks backed by billions of dollars in advertising. This was basically correct. It also didn’t matter a bit. Maybe TikTok set the industry on a new course. Or maybe it saw the future more clearly than the other apps did and simply beat them to it.